Israeli Pulp

I've seen very little about romance publishing in Israel other than Paul Grescoe's brief reference to Harlequins being published

under a licensing arrangement in Israel, where the company had some difficult dealings but enjoyed among the highest penetrations of any country in the world. In recent years, however, Hebrew has become one of a couple of languages that are no longer part of the Harlequin world. (173)

I was therefore pleased to see some mention of romance in Rachel Leket-Mor's about "IsraPulp: The Israeli Popular Literature Collection at Arizona State University." She describes the items in the collection as being "on the ostracized fringe" (2) and adds that

Collecting, preserving, and enabling access to these materials are the responsibility of librarians and stewards of cultural memory, as demonstrated in cultural historian Robert Darnton’s essay “The Library in the New Age” (2008):

The criteria of importance change from generation to generation, so we cannot know what will matter to our descendants. They may learn a lot from studying our Harlequin novels or computer manuals or telephone books. Literary scholars and historians today depend heavily on research in almanacs, chapbooks, and other kinds of “popular” literature, yet few of those works from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have survived. They were printed on cheap paper, sold in flimsy covers, read to pieces, and ignored by collectors and librarians who did not consider them “literature.” (5)

Leket-Mor's article (which is freely available online) isn't just about the University's collection: it also includes a short "history of Hebrew non-canonized literature since the 1930s." She begins earlier, though, with related literature published elsewhere, and so she mentions that

In 1937, the two major Yiddish dailies in Warsaw, Haynt and Der Moment, started to publish sensational novels in booklets. The first installment was distributed with the Friday newspaper edition, and the rest of the series was sold separately, as a side business for the publishers. These novels, epitomized by the serialized Sabine and Regine, were usually titled after their female protagonists, featuring urban romance stories with a dash of erotic intricacies. By 1938, the distribution of these Damsel-in-Distress booklets outnumbered any Jewish newspaper in Warsaw (Shmeruk 1982; Cohen N. 2003b, 2008).

These serialized Yiddish novels were also exported to Erets-Israel, “boxes upon boxes of ‘Sabines’ and ‘Regines’,” by Jewish journalists who emigrated from Poland with the Fifth ‘Aliyah (1929–1939). Inspired by their popularity, similar series came out in Hebrew during the 1930s and 1940s. (9)

It was the

ha-Roman ha-Za'ir publishing house of the Farago Brothers [...] which was the steadiest enterprise in the non-canonized domain, and [...] therefore epitomized the concept of pulp fiction in colloquial Hebrew. According to the thorough study of Gavriel Rosenbaum (1999), the firm operated from 1939 to 1961, first under the name of ha-Roman ha-Za'ir [The Tiny Novel], and since 1952 as ha-Kulmos [The Quill] [...] ha-Roman ha-Za'ir and ha-Kulmos published about 700 chapbooks during their twenty-two years of continuous activity. Some of the titles were retranslated from Hungarian and republished because the publishers believed that the Hebrew register used in the first editions was too elevated. The scope of their output covered romance stories, along with crime and adventure stories spiced with romance, in urban settings. Erotic elements were moderate, and these never turned into pornography. According to Rosenbaum (1999), the Farago brothers took their publishing business seriously and insisted on well-translated, proofread, entertaining texts. (17-18)

Apparently

The activity of the pulp industry subsided during the seventies and by the end of that decade was practically gone. Among the genres that were still being printed were Westerns, Patrick Kim titles, children’s titles (including comic books), romance, mystery, and pornography, which became more explicit in nature. (36)

Arizona State University's Israeli Popular Literature Collection contains "several novels published by Mizrahi" (53) from this period but it would seem that the collection's body of erotic/pornographic texts is larger than its list of romances because the former includes

almost a complete run of all published Stalags, as well as other erotic and pornographic titles, some of them represent the gay culture. Publishers include Ramdor, ha-Sifriyah ha-Ketanah, Mor, Reno, Narkis, Hermesh, Yam-Suf, ha-Te’omim, ha-Sha'ashu'a ha-Kal, Orr, ha-Roman ha-Romanti ha-Refu’i [the Medical Romance]. (53)

One interesting difference between romances published in the UK and US is that

the overwhelming majority of non-canonized texts in Hebrew literature through its different periods were written by men, even when the targeted audience was clearly women, as in the case of romance novels issued by ha-Roman ha-Za‘ir press [...]. This fact is quite surprising when considering, for example, the American subsystem of romance fiction, dominated by female authors (Radway 1991). The far-reaching consequences of this on the writing style, representation of women, and assumed readers of Israeli popular literature are demonstrated in the terminology of erotic literature: according to Ben-Ari (2006), those erotic and pornographic texts that were written by women are not essentially different than those written by men, as the former adapted the norms prevailing in this genre. This is the only study that touches on this issue. (16)

----------

Grescoe, Paul. The Merchants of Venus: Inside Harlequin and the Empire of Romance. Vancouver: Raincoast, 1996.

Leket-Mor, Rachel. "IsraPulp: The Israeli Popular Literature Collection at Arizona State University," Judaica Librarianship 16.4 (2011).

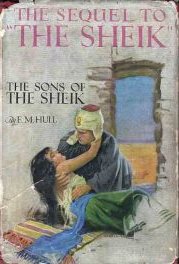

I think it's important to distinguish between novels which contain an entire romance arc and which are linked to other such novels by an ongoing cast of characters and/or adventures (e.g. E. M. Hull's The Sheik and The Sons of the Sheik, Georgette Heyer's These Old Shades and Devil's Cub or Jo Beverley's

I think it's important to distinguish between novels which contain an entire romance arc and which are linked to other such novels by an ongoing cast of characters and/or adventures (e.g. E. M. Hull's The Sheik and The Sons of the Sheik, Georgette Heyer's These Old Shades and Devil's Cub or Jo Beverley's  It is known that "Scents can influence people’s attitudes and behavior [...]. The scent of chocolate, for instance, evokes pleasure and arousal for most consumers" (Doucé et al 3). What, then, would happen if a bookshop was filled with a smell of chocolate so subtle that "none of the customers spontaneously noticed the chocolate scent" (7)?

It is known that "Scents can influence people’s attitudes and behavior [...]. The scent of chocolate, for instance, evokes pleasure and arousal for most consumers" (Doucé et al 3). What, then, would happen if a bookshop was filled with a smell of chocolate so subtle that "none of the customers spontaneously noticed the chocolate scent" (7)? ia Cheyne's "research focuses on representations of disability and illness in fiction, especially popular genres such as science fiction, romance, horror and crime" and

ia Cheyne's "research focuses on representations of disability and illness in fiction, especially popular genres such as science fiction, romance, horror and crime" and  In Zorzi's case, the barriers relate primarily to his size but Anthony is restricted by his low social class and Amoret by her gender. Indeed, in the first book in the series Amoret is only able to participate in the adventure as a result of dressing as a boy. Thinking about these differing barriers in the light of the social model of disability reminded me of Aristotle's ideas about women:

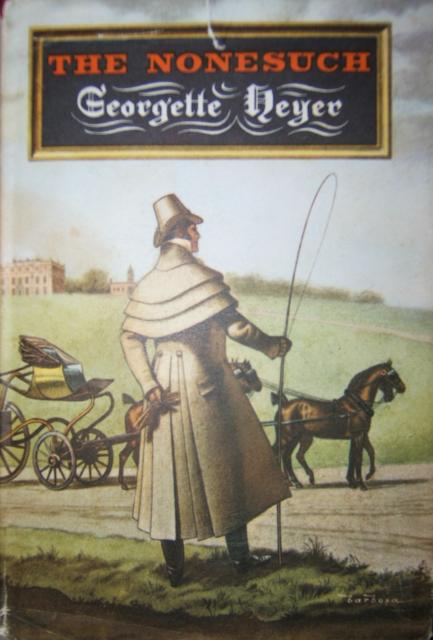

In Zorzi's case, the barriers relate primarily to his size but Anthony is restricted by his low social class and Amoret by her gender. Indeed, in the first book in the series Amoret is only able to participate in the adventure as a result of dressing as a boy. Thinking about these differing barriers in the light of the social model of disability reminded me of Aristotle's ideas about women: My article about Georgette Heyer is out now in the latest issue of the Journal of Popular Romance Studies. It's called "

My article about Georgette Heyer is out now in the latest issue of the Journal of Popular Romance Studies. It's called "

I don't think you need to be Freud to work out the symbolism of that warm pistol but if it still wasn't clear, there's a rather obvious clue in Boone's statement that "I never hired out my gun to the highest bidder. That to a man is like whorin' to a woman - the end of the line" (218).

I don't think you need to be Freud to work out the symbolism of that warm pistol but if it still wasn't clear, there's a rather obvious clue in Boone's statement that "I never hired out my gun to the highest bidder. That to a man is like whorin' to a woman - the end of the line" (218).