In "Happily Ever After ... And After: Serialization and the Popular Romance Novel" An Goris takes a closer look at what happens after the "happily ever after" in series by Nora Roberts and J. R. Ward but since I haven't read them, I thought I'd excerpt some of An's more general comments about series and romance:

According to information provided by RWA, sixty-three percent of the top bestselling romances between 2007 and 2011 were part of a narrative series (Fry). Roughly eighty-five percent of the romance novels that appeared on the extended New York Times bestseller list in April 2013 similarly belong to a narrative series. Two of the most famous romance novels of the last decade, Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight (2008) and E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey (2011), are likewise part of a narrative series.

As a narrative format, serialization is neither new nor rare. It is used frequently in a wide range of genres and media, including literature, film, television, radio, and comics. [...] Serialization’s status as an exceptionally effective commercial tool makes romance’s apparent historical reserve towards the form all the more remarkable [...] if romance is a genre that understands the commercial currents of the publishing industry better than most, what factors might explain its historical reserve towards the commercially successful serial format? (Goris)

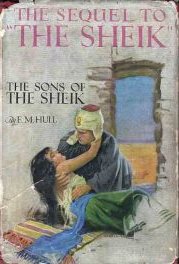

I think it's important to distinguish between novels which contain an entire romance arc and which are linked to other such novels by an ongoing cast of characters and/or adventures (e.g. E. M. Hull's The Sheik and The Sons of the Sheik, Georgette Heyer's These Old Shades and Devil's Cub or Jo Beverley's Company of Rogues series) and series in which the central protagonists' relationship develops over a number of novels (as in the Twilight series).

I think it's important to distinguish between novels which contain an entire romance arc and which are linked to other such novels by an ongoing cast of characters and/or adventures (e.g. E. M. Hull's The Sheik and The Sons of the Sheik, Georgette Heyer's These Old Shades and Devil's Cub or Jo Beverley's Company of Rogues series) and series in which the central protagonists' relationship develops over a number of novels (as in the Twilight series).

An Goris describes the first kind of series thus:

The character-based romance series is structured around a group of recurring characters (siblings, colleagues, friends, inhabitants of a small town, etc.). Each installment in the series features the complete romance narrative of one member of the group. The narratives are connected to each other via the recurring characters and sometimes via non-romance subplots. The type’s defining serialization strategy is to locate the serial elements not in the romance plot but elsewhere in the narrative. This allows for the inclusion of the HEA in each individual installment in the series.

Harlequin/Mills & Boon almost always publish series of this kind. One of the earliest I know of is Mary Burchell's Warrender Saga: the first book was published in 1965 and the last in 1985. They have experimented with the second type of series but it presumably wasn't very successful because I could only think of one definite example: Lynne Graham's The Drakos Baby series. I have a vague recollection of a pair of novels in which the heroine of the first book died and her sister than married its hero in the second. If anyone can identify them, or think of other HM&B series of the second kind, please let me know!

I think the near-complete absence of type-2 series at HM&B might have something to do with the expectation that Harlequin/Mills & Boon romances will include a complete romance plot arc in every book. This may have been shaped not just by a desire to publish a homogenous product but also by the way in which the novels were sold: for much of the company's history category romances were novels which had short shelf lives. I imagine it would be intensely annoying for many readers to pick up what they thought was a romance, only to discover that the story arc had begun in a previous and now unavailable novel.

An Goris speculates that

Romance’s initial hesitation towards narrative serialization has to do [...] with the opposing narrative dynamics that drive the romance and the serial forms. Romance is a generic form predicated on achieving narrative closure (Capelle 145; Pearce, Romance Writing 146). It reaches this closure in the happy end to the love story that is its main focus. This happy end – known in the romance community by the acronym HEA, which stands for Happy Ever After – is not a coincidental element of the genre, but is universally recognized as one of the romance novel’s defining and distinguishing features (Regis 9). The serial, by contrast, is a narrative from defined by its lack of a definitive ending.

Were the Twilight and Fifty Shades series marketed as genre romance? I have a feeling that they weren't. And as far as I know, Diana Gabaldon has always insisted that her Outlander series is not romance. Lord Peter Wimsey may be a hero close to the hearts of many romance readers, but the novels in which he finds love with Harriet Vane are shelved as detective fiction. I think one could say something similar about Roarke in J. D. Robb's In Death series. Catherine Cookson wrote plenty of series, but her novels are usually classified as historical fiction, sagas or romantic fiction rather than as romance. This illustrates Goris's conclusion about this second type of series: it

takes up a peripheral position in the romance system. The generic identity of many novels in such romance-based series is fuzzy. It tends to oscillate between romance, urban fantasy, and mystery. The novels are often primarily advertised as belonging to a genre other than romance. In bookstores and libraries, for example, they are usually placed in the fantasy, mystery, or science fiction section, which implies an exclusion from the romance category that is shelved elsewhere in the same space.

Goris suggests that there is also a third type which

combines the strategies of the other two types. It is a narrative that is formally structured around a group of recurring characters with each installment focusing on the courtship plot of one member of the group (with another member or an outsider). Yet each installment also includes the narrative representation of substantial romantic events between at least one couple that is formally the romantic focus of another installment in the series.

I can't think of many examples but I have a feeling at least one of Suzanne Brockmann's series might fit this description.

One of the most important possibilities opened up by by series of the first and third kinds, and also by those in the second if the protagonists make a permanent commitment to each other part-way through the series rather than at its end, is that they can show what happens after the "happily ever after":

Traditionally, the HEA [...] functions more as a narrative promise than a narrative actuality. It implies romantic love, stability, and happiness for its protagonists, but it does not include extensive actual representations of this happiness.

This fundamentally changes in the serialized romance narrative in which the fictional universe must be extensively represented after the happy end of at least one (and often multiple) couple(s) has been reached.

Clearly this does offer interesting opportunities but I think it can be less than interesting, and indeed can make a series seem increasingly unrealistic, if it transpires that an entire social circle is falling into married bliss like dominoes, with each previous pairing making brief appearances in which they flaunt their ongoing bliss along with the increasing size of their family. By definition, I imagine this is a problem which is likely to be limited to series of the first and third kinds.

An concludes that

The boom of narrative serialization has the potential to be somewhat of a game changer for the romance genre. The incorporation of serial dynamics into the romance form is not only pushing the genre’s traditional narrative boundaries but also opening up a new narrative space in which the genre is articulating its core romantic fantasy to previously unprecedented extents.

This may well be true, but "the genre's traditional narrative boundaries" haven't been "traditional" for very long given that "the romance genre" emerged in its current Romance Writers of America defined form, only relatively recently. Romances (in the sense of stories featuring "a central love story and an emotionally-satisfying and optimistic ending") have, of course, been around for centuries, but I don't think that they've constituted a recognised genre (i.e. a distinct marketing category) for very long (although, as a medievalist, my idea of what constitutes a short time is perhaps a little longer than some other people's). In any case, I don't think it ever has been understood that way in the UK, where "romance" has tended to be more broadly defined and used as a synonym for "romantic fiction."

I wonder if perhaps what's happening is that as "romance" in the US has acquired more sub-genres it's been increasingly influenced by the norms of those other genres (such as mystery and fantasy) in which series (of type 2) were more common. As long as these new romantic series continue to have romantic relationships at their cores, complete with happy-ever-afters, I'd see that as an expansion of "romance."

Some purists, however, would perhaps see the situation as one in which "romance" is being diluted by non-romance elements and in which the HEA loses some of its power when it is no longer the triumphant conclusion to the protagonists' story. Maybe that's why in 2012 it was announced that

the RITA, the academy award of romantic fiction, is discontinuing the Novel with Strong Romantic Elements category after this year. After much discussion both among themselves and with RWA, the Women’s Fiction chapter spearheaded by Therese Walsh will disband because of some wording in RWA’s bylaws: “…to advance the professional interests of career-focused romance writers through networking and advocacy…” (Flaherty)

It looks, however, as though the Women's Fiction Chapter of the RWA is still in existence.

----

Flaherty, Liz. "The times they are a-changin’…" 6 December 2012.

Goris, An. "Happily Ever After ... And After: Serialization and the Popular Romance Novel." Americana 12.1 (2013).

Interesting categories,

Interesting categories, Laura, and I do think revisiting HEA couples over time in any of the forms is interesting.

As you mentioned my Company of Rogues Regencies, I thought I'd refer to them. Most of the settled couples only appear in subsequent books if a character with their qualities is naturally required in the storyline. However, Beth and Lucien from An Unwilling Bride have appeared more than most. (I think. I've not checked!)

This is because theirs was the most conflicted relationship from the first, and though it's resolved at the end, readers could well wonder what would happen in the future with all the normal ups and downs of life. That interested me, too.

So I enjoyed giving them roles so readers could see how they were handling disagreements, and also see that different points of view don't magically melt under the warmth of love, and have to be dealt with, but can be without either having to surrender their identity to the other.

That's what I hope comes through, anyway. Many of the other couples are so settled they hardly show up at all. For which, I'm sure, they're very grateful. Showing up usually means becoming entangled with a problem.

Jo

Many of the other couples are

Even though I probably shouldn't, as a reader, I tend to imagine that all of an authors' books are set in the same "world" unless I'm specifically told otherwise. So, for example, I have an idea of Heyer's London which is inhabited by most of her characters, even though few of her novels are actually linked and I imagine that Austen's characters could potentially meet each other offpage. The way you deal with previous characters fits in with that pre-existing assumption of mine and it seems realistic for many characters not to reappear on the page given the logistics involved in bringing characters together when they live in distant parts of the country and the fact that people who've settled down and have family or other pressing commitments can't easily drop everything and get involved with the new couple's problem. In fact, barring them all being present for the "season," if too many previous couples showed up I'd begin to feel that their world was a stage and that they'd been waiting patiently in the wings to reappear, rather than having a normal existence of their own.

Funnily enough, I didn't have any doubts about Beth and Lucien's future at all because they seemed to enjoy discussing their ideological differences and I didn't think those differences would have all that much impact on a practical level once the pair of them had come to respect each other's opinions.

When I began reading more

When I began reading more romance than SFF the series thing really stood out to me. It seemed to me that a romance series was almost always like An Goris' 3rd type; a family of sisters or brothers each having their romance in turn and sometimes I think that is why military units and werewolves or even the dreaded small town setting are such staples because they offer the chance for individual but linked stories. I think people want to read not just that a couple's HEA is really truly an HEA because we re-visit and confirm this but that the community or world they are a part of supports them and connects them. I also wonder if this is so because so many romance genre characters are shown as having problematic families of origin and believing in their HEA means also seeing them settled into new families made from their choices?

Good point about problematic

Good point about problematic origins. It's not always so, but such things are often the conflict/barriers of a romance novel, and seeing them overcome is key to the HEA. Also seeing family rifts healed.

Whether we revisit the world or not (yes, Laura, I talk about my Rogues World and Malloren World) as a reader I want most of the problems sorted by the end so that the couple has the best possible chance of a long, happy future together. If leech-like drunken relatives and sleazy friends from the bad days are still hanging about, it undermines.