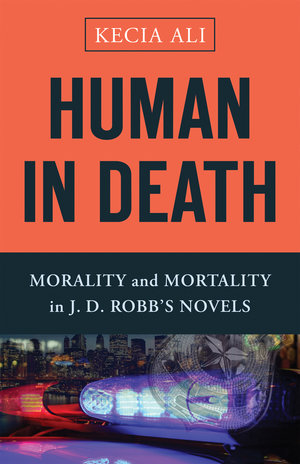

Kecia Ali's "Human in Death: Morality and Mortality in J. D. Robb's Novels"

There is a moment in J. D. Robb's Celebrity in Death in which, Kecia Ali observes, Robb seems to "address the place of fiction - her own work - in the world" (152) through the words of an actor who states that:

"I'm good at my work. I'm damn good at it and I feel strongly what I do is important [...] without art, stories, and the people who bring those stories to life, the world would be a sadder, smaller place." (46)

Robb's work may make the world a happier place by entertaining her readers, but perhaps she also expands their world by touching on a range of quite serious topics.

Kecia Ali's Human in Death: Morality and Mortality in J. D. Robb's Novels argues that the novels in Robb's In Death series

Kecia Ali's Human in Death: Morality and Mortality in J. D. Robb's Novels argues that the novels in Robb's In Death series

explore vital questions about human flourishing.

Through close readings of more than fifty novels and novellas published over two decades, Ali analyzes the ethical world of Robb’s New York circa 2060. Robb compellingly depicts egalitarian relationships, satisfying work, friendships built on trust, and an array of models of femininity and family. At the same time, the series’ imagined future replicates some of the least admirable aspects of contemporary society. Sexual violence, police brutality, structural poverty and racism, and government surveillance persist in Robb’s fictional universe, raising urgent moral challenges. So do ordinary ethical quandaries around trust, intimacy, and interdependence in marriage, family, and friendship.

Ali celebrates the series’ ethical successes, while questioning its critical moral omissions. She probes the limits of Robb’s imagined world and tests its possibilities for fostering identity, meaning, and mattering of human relationships across social difference. Ali capitalizes on Robb’s futuristic fiction to reveal how careful and critical reading is an ethical act.

For example, although Robb's protagonist, Eve Dallas, "frequently uses violence in appropriate and measured ways to stop criminals or protect herself, colleagues, or civilians," Ali highlights the need to read carefully and critically given that at other times Dallas

abuses her power, or threatens to. Readers - like Dallas' colleagues - become complicit in these casual brutalities. Readers identify with Dallas and root for her. She has suffered traumatic violence herself and commands what P.D. James terms "reader identification and loyalty." [...] Reader loyalty means that when she hurts people, especially but not only when they hurt her first, readers tend to be on her side.

This is the case even when she is in the wrong. (89)

In such circumstances, the novels may prompt the reader to adopt positions which Ali regards as unethical. However, Ali looks more favourably (albeit still with a critical lens) at other aspects of the novels, such as Dallas's rejection of "the claim that some people simply deserve better lives than others" (96).

Death, too, is portrayed as egalitarian:

In December 2060, Dallas' detectives hang a sign over the squad's break-room door, joining a jumble of holiday decorations [...]:

NO MATTER YOUR RACE, CREED, SEXUAL ORIENTATION, OR POLITICAL AFFILIATION, WE PROTECT AND SERVE, BECAUSE YOU COULD GET DEAD.

Erected as a joke, the sign strikes Dallas' fancy. She decrees that it will remain after the sad Christmas tree and other seasonal debris are gone. It expresses a core truth: death equalizes [...] Not only is death universal, so is vulnerability. (95)

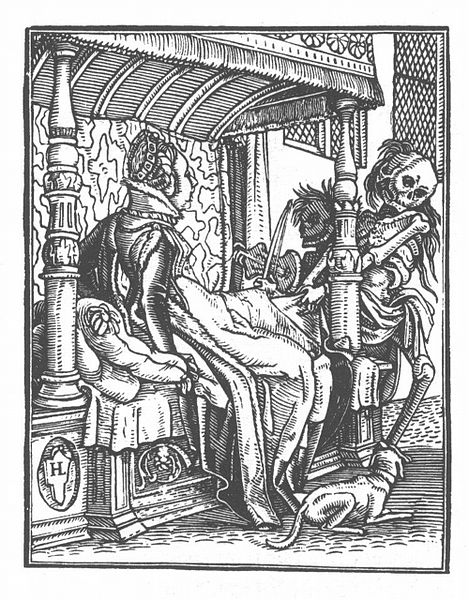

Naturally (given my academic background) this reminds me of medieval and early modern depictions of death.

In the illustrations and texts of the Dance of Death, individuals from both lay and clergy, of high to low estate, of a variety of creeds (at least in the Spanish version), young and old, male and female, are forced to join the dance.

Death and the Duchess: Holbein d. J.; Danse Macabre. XXXVI. The Duchess

Death and the Duchess: Holbein d. J.; Danse Macabre. XXXVI. The Duchess

The illustration above, by Hans Holbein, dates from the first half of the sixteenth century and depicts two skeletal representatives of Death arriving to take a Duchess from her bed. Other illustrations in the series show the moment at which Death approaches individuals from different social classes. The modern novels of the In Death series use words, rather than images, to portray variations in social class and how they affect the contexts of individuals' deaths:

the form of difference to which the series attends most clearly is class. Juxtapositions between rich and poor victims pepper the series. Its first installment juxtaposes the deaths of a wealthy woman from a prominent family working as a licensed companion and an older LC struggling to get by. Another opens by contrasting two murders: in his lavish home, a rich man's "death had come to him on the luxurious sheets of his massive, silk-canopied bed." A poor young woman's death the night before had occurred "on the stained mattress tossed on the floor of a junkie's flop." The surroundings diverge, but the end result is the same: hence the protecting and serving that the squad sign proclaims. (95-96)

That "squad sign" with its warning that "YOU COULD GET DEAD" also recalls for me the warning issued by three corpses (who are, however, a little more emphatic about the issue), in the tale of The Three Living and the Three Dead: they tend to state some variation of "What you are now, we once were; what we are now, you shall be" (as at Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini).

Three Living and Three Dead: Detail of a miniature of the Three Living and the Three Dead, from the De Lisle Psalter, England (East Anglia), c. 1308 – c. 1340, Arundel MS 83, f. 127v (see the British Library blog for more details)

Three Living and Three Dead: Detail of a miniature of the Three Living and the Three Dead, from the De Lisle Psalter, England (East Anglia), c. 1308 – c. 1340, Arundel MS 83, f. 127v (see the British Library blog for more details)

The connection between these medieval/early modern works and the futuristic In Death series may seem tenuous but, as Ali observes "Robb often plays with literary analogues and antecedents [...] e.g. Witness in Death pays homage to Agatha Christie) [...] "Chaos in Death" engages The Strange Case of Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde" (176) and, in addition, Ali points out ways in which the novels contain more than one "blast from the past" which "connects the future with the past":

Robb's retrograde jargon of "mental defectives" and "violent tendencies" suggests biological determinism [...] the panhandler licenses that beggars must display recall the poor badges of sixteenth-and seventeenth-century England. (106)

It seems not inappropriate, therefore, for an academic response to her work similarly to make connections between her novels and older works of literature and art.

It might be a little bit too fanciful, however, to think of Eve Dallas, who "seeks justice for the innocent and beloved as well as the guilty and the jerks" (114) as a handmaiden of the goddess Poena (from whose name the word "penal" is derived) and of whom Anthony Trollope wrote in Framley Parsonage that:

Poena, that just but Rhadamanthine goddess, whom moderns ordinarily call Punishment, or Nemesis when we wish to speak of her goddess-ship, very seldom fails to catch a wicked man though [...] the wicked man may possibly get a start of her. (Chapter 47)

Even so, it's intriguing how closely and explicitly entwined Dallas' role is with death and, moreover, that it has a spiritual element: "For her, being a cop is a calling. A priest compares Dallas' vocation to his own" (46) and "In a dream conversation with a murder victim who had been posing as a priest, Dallas rejects sin as out of her "jurisdiction," telling him, "Murder is my religion" (151). And it is also mentioned that Dallas was "a 'mythical figure' while [Peabody] was at the [police] academy" (48).

![Poena/Poine: Atreus, king of Mycenae, sprawls mortally wounded on his throne. [...] To the right of the throne [...] P](http://www.vivanco.me.uk/sites/vivanco.me.uk/files/images/Poine (Poena).jpg)

Here "Atreus, king of Mycenae, sprawls mortally wounded on his throne. [...] To the right of the throne [is] Poine, the winged goddess of retribution" who was known as Poena by the Romans. In other words, she's on the scene of a murder to investigate and arrives quickly due to her wings; Dallas has to make do with a flying car. The image is taken from a scene depicted on a "Two-handled jar (amphora) depicting the murder of Atreus. Greek, South Italian, Late Classical Period about 340–330 B.C." Appropriately given Ali's academic affiliation, this is also from Boston, albeit the Museum of Fine Arts. "Images of artworks the Museum believes to be in the public domain are available for download" under terms of use which permit "limited non-commercial, educational, and personal use."

----

Ali, Kecia. Human in Death: Morality and Mortality in J. D. Robb's Novels. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2017.

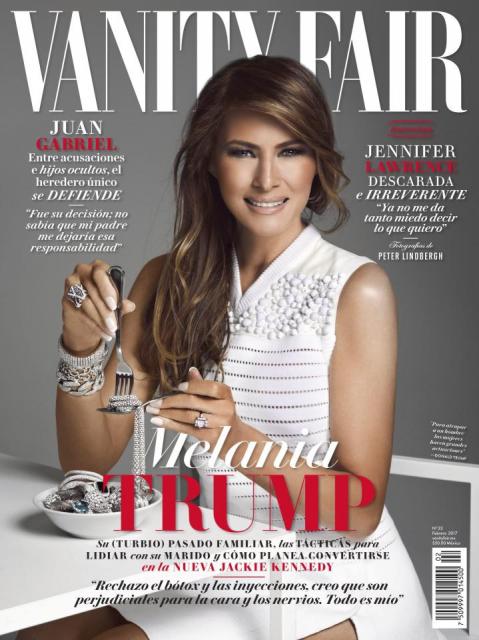

Melania Trump, eating diamonds, on the cover of Vanity Fair (Mexico)

Melania Trump, eating diamonds, on the cover of Vanity Fair (Mexico)

Focusing on the representation of lesbianism in mainstream erotic fiction, the essay principally investigates the idea of experimenting with one's sexual orientation as an aspect of the cultural shift toward embracing sex practices that depart from the norm. In mainstream erotic fiction, I will suggest, female-female sexuality is primarily represented in the context of, indeed, as an element of, heterosexual, white, middle-class fantasy. [...] One particular novel, Till Human Voices Wake Us by Patti Davis, serves as a key text for analysis. A self-published novel about an upper-class American woman who falls in love with her sister-in-law after the death of her child, Till Human Voices Wake Us appears to have little claim to either "literary" or "erotic" merit and would probably be completely unknown except for the fact that Davis happens to be the daughter of Ronald Reagan. However, an analysis of this novel and its discursive context will provide some insight into the uncertain position of same-sex desire in relation to mainstream women's erotic fiction. (150)

Focusing on the representation of lesbianism in mainstream erotic fiction, the essay principally investigates the idea of experimenting with one's sexual orientation as an aspect of the cultural shift toward embracing sex practices that depart from the norm. In mainstream erotic fiction, I will suggest, female-female sexuality is primarily represented in the context of, indeed, as an element of, heterosexual, white, middle-class fantasy. [...] One particular novel, Till Human Voices Wake Us by Patti Davis, serves as a key text for analysis. A self-published novel about an upper-class American woman who falls in love with her sister-in-law after the death of her child, Till Human Voices Wake Us appears to have little claim to either "literary" or "erotic" merit and would probably be completely unknown except for the fact that Davis happens to be the daughter of Ronald Reagan. However, an analysis of this novel and its discursive context will provide some insight into the uncertain position of same-sex desire in relation to mainstream women's erotic fiction. (150) I'm probably going to be moving house soon, which means I'll have to part with quite a few of my books. I'm treating this as an opportunity to take a break from my current project and concentrate on books I've been meaning to read for a while; one of them is Amanda Vickery's The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England (there's a detailed review

I'm probably going to be moving house soon, which means I'll have to part with quite a few of my books. I'm treating this as an opportunity to take a break from my current project and concentrate on books I've been meaning to read for a while; one of them is Amanda Vickery's The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England (there's a detailed review  In “What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?”: Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel," Marlon B. Ross states that

In “What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?”: Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel," Marlon B. Ross states that ia Cheyne's "research focuses on representations of disability and illness in fiction, especially popular genres such as science fiction, romance, horror and crime" and

ia Cheyne's "research focuses on representations of disability and illness in fiction, especially popular genres such as science fiction, romance, horror and crime" and  In Zorzi's case, the barriers relate primarily to his size but Anthony is restricted by his low social class and Amoret by her gender. Indeed, in the first book in the series Amoret is only able to participate in the adventure as a result of dressing as a boy. Thinking about these differing barriers in the light of the social model of disability reminded me of Aristotle's ideas about women:

In Zorzi's case, the barriers relate primarily to his size but Anthony is restricted by his low social class and Amoret by her gender. Indeed, in the first book in the series Amoret is only able to participate in the adventure as a result of dressing as a boy. Thinking about these differing barriers in the light of the social model of disability reminded me of Aristotle's ideas about women: My article about Georgette Heyer is out now in the latest issue of the Journal of Popular Romance Studies. It's called "

My article about Georgette Heyer is out now in the latest issue of the Journal of Popular Romance Studies. It's called " If you've ever wondered why so many romance heroines are (wrongly) identified as "gold-diggers," Stephen Sharot's "Wealth and/or Love: Class and Gender in the Cross-Class Romance Films of the Great Depression" may provide the answer:

If you've ever wondered why so many romance heroines are (wrongly) identified as "gold-diggers," Stephen Sharot's "Wealth and/or Love: Class and Gender in the Cross-Class Romance Films of the Great Depression" may provide the answer: The latest issue of the Journal of Popular Culture came out a few days ago and although none of the articles were directly about romance, quite a few of them have some relevance to it. For example, Kirk Combe begins his article about the "bourgeois rake" in rom-coms by stating that

The latest issue of the Journal of Popular Culture came out a few days ago and although none of the articles were directly about romance, quite a few of them have some relevance to it. For example, Kirk Combe begins his article about the "bourgeois rake" in rom-coms by stating that