Team @MillsandBoon has arrived in Sheffield for @FestivalMind! And look at our gorgeous circus tent! pic.twitter.com/qDoeQKqjLj

— Flo Nicoll (@flonicoll) September 17, 2016

The three-person Team @MillsandBoon was joined by Team Romance Scholar to take part in a panel discussion about romance organised by the University of Sheffield's Festival of the Mind. The event was recorded and the plan seemed to be to put up a podcast of the discussion so if that happens I'll mention it on the blog. In the meantime, I'll just write up a few comments focussed on the academic side of the panel discussions. Here's how we were described on the Festival's website:

On Saturday 17 September from 1-2pm there will be a panel discussion (see below), followed by the lecture at 2pm.

About the panel discussion

Can anyone write a romantic novel? What are editors looking for in their next romance? How do the authors come up with their ideas? And is it all just escapism, or is there literary value to be found in these texts?

Our panel of experts will answer your burning questions about Mills & Boon romantic novels.

The panel:

- Flo Nicoll, Senior Editor for Mills & Boon

- Susan Stephens and Heidi Rice, popular authors for Mills & Boon

- Dr Laura Vivanco, whose academic text For Love and Money, published in 2011, explored the literary art of Mills & Boon romantic novels

- Dr Amy Burge, whose recent monograph Representing Difference in the Medieval and Modern Orientalist Romance (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016) analysed race, religion, multiculturalism and gender in romance

- Fiona Martinez, Sheffield Hallam University’s Vice-Chancellor Scholarship PhD candidate, whose own research explores the romance genre as a feminist endeavour.

Leading the discussion and then giving the lecture on Mills & Boon romance was Val Derbyshire (you can read about some of her M&B research here and here).

Team Romance Scholar fielded a number of questions.

As part of a discussion about heroes, Amy was able to give extremely detailed feedback on the numbers of sheikh heroes in Mills & Boon novels. Anyone wanting more information about that can read Amy's book on Representing Difference in the Medieval and Modern Orientalist Romance. There have also been a lot of Mediterranean heroes (Greek, Italian and Spanish mainly) and Flo Nichols suggested that although in recent years authors had been drawn to experiment with Russian heroes (presumably because of Russian oligarchs buying up UK football clubs etc) they've not been as popular as hoped with readers.

In response to a question about diversity, Amy suggested that although the Cinderella archetype may mean there are a fair number of heroines of working-class origin, there is less balance with regards to ethnicity/race. Flo argued that the company's output is diverse but also suggested that readers' responses have a big impact on Harlequin Mills & Boon's attempts at ethnic/racial diversification beyond sheikhs etc because they pay a lot of attention to sales figures when deciding what works and what doesn't. That said, Flo also felt that the submissions they receive have not varied very much, perhaps because aspiring authors write what they think HM&B want (based on what has already been published). She seemed interested in receiving submissions with heroes and heroines from a wider range of ethnicities/races.

I responded to a question about changes in the novels over time but I'm not the best at remembering dates so I'm afraid I might have been out by a decade or so when making some of my comments. Anyone wanting to know more about the history of Mills & Boon should read jay Dixon and Joseph McAleer's books on the topic but I'll quote a little bit of what they have to say here.

Mills & Boon began as a general publisher but from the 1930s "until the mid-1950s, general books were dropped and the firm concentrated on romance fiction" (Dixon 17):

The 1930s witnessed a major shift in the firm's direction which reflected changes in the marketplace. As library sales increased between the wars, fiction displaced the educational and general lists. At the same time, Mills and Boon specialized in its most successful type of novel, the romance. (McAleer "Scenes" 267)

However, McAleer also observes that:

it is difficult to speak of a specific Mills & Boon editorial policy before the Second World War. The reason is obvious: Charles Boon [...] was still a general publisher at heart. The 1930s was still a time of experimentation, and novels were novels in their own right. Boon did not impose many restrictions on his authors. (Passion's Fortune 145)

Nonetheless, it was "During this decade [that] the characteristics of the archetypal Mills & Boon heroine and hero began to fall into place" (McAleer Passion's Fortune 150).

In the 1940s Mills & Boon "added a strong dose of patriotism and social commentary. John Boon believed that Mills & Boon has not been given sufficient credit for maintaining morale with its novels during the war" (McAleer Passion's Fortune 171-72). I've quoted some of McAleer's thoughts on Mills & Boon and the NHS here and he also mentioned that:

when [Joyce] Dingwell's The Girl From Snowy River (1959) was published, a tale of an English woman emigrating to Australia, Boon sent a copy to the Hon. A. R. Downer, MP (then Australian Minister of Immigration), at Australia House, with the message, 'We feel it is good propaganda for immigration.' (Passion's Fortune 103).

Given that the panel was in Sheffield, it might be worth mentioning here that I contributed a few early Mills & Boon novels to Sheffield Hallam University's Readerships and literary cultures collection (1900-1950), "a collection of books which reflects the wide range of literary tastes during the period 1900-1950". I think the M&Bs are only a very small proportion of the collection, which "consists of over 1200 novels, most in early editions, by 240 different authors" (Middlebrow Network) and I'm not sure how representative their Mills & Boons holdings are. Certainly, the ones I sent them were acquired on the non-academic criterion of whether they could be acquired cheaply on Ebay. As Amy has discovered, though, even the libraries which might be expected to hold a complete list of all the Mills & Boons ever published (such as the British Library and the National Library of Scotland) have lacunae.

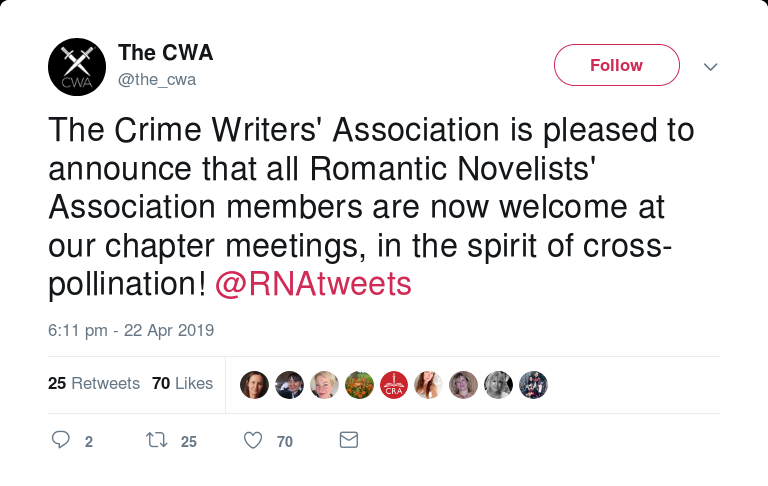

When asked whether the status of romance is likely to improve, Flo suggested that (a) it ought to if people paid attention to the sales figures and (b) that the situation is somewhat better in the US. I suggested that perhaps the emergence of the field of popular romance studies would also help improve the genre's reputation. In the study of popular culture more generally, academics working on crime/detective fiction and science fiction have been able to ameliorate the status of those genres so I'm hopeful that academic study of popular romance will be able to demonstrate that romance novels reward analysis in a variety of ways and do deserve to be treated with respect.

As Fiona pointed out, the lack of respect for romance has seeped into the study of authors in other genres too, making assessement of their oeuvres less than complete. She's studying a range of prize-winning authors including Jeanette Winterson and has found that the romantic elements of their novels have been neglected by literary critics. She, however, is focussing on those elements and her work will therefore demonstrate that romance and its conventions can be found well beyond the covers of novels marketed as "romance". This may, perhaps, help reduce the stigma attached to works which are marketed that way.

Fiona has now written a post of her own about the event.

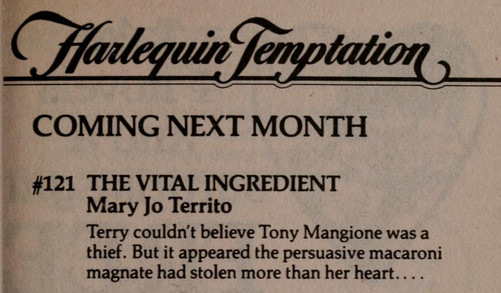

I'm hoping the booklet which gives a full outline of Val's talk might also be put online but perhaps it won't due to copyright restrictions because it includes a lot of images of Mills & Boon covers. As I said, though, the Festival organisers did promise they'd be making some material available online so when they do, I'll post about it. Here's a glimpse of one page via a tweet from Amy:

Speaks for itself @FestivalMind @MillsandBoon @Valster11 pic.twitter.com/7D8ShUKIzo

— Amy Burge (@dramyburge) 17 September 2016

----

Dixon, jay. The Romance Fiction of Mills & Boon 1909-1990s. London: UCL Press, 1999.

McAleer, Joseph. Passion's Fortune: The Story of Mills & Boon. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

McAleer, Joseph. “Scenes from Love and Marriage: Mills and Boon and the Popular Publishing Industry in Britain, 1908-1950.” Twentieth Century British History 1.3 (1990): 264-288.

The artwork in the @FestivalMind spiegeltent was amazing. Vampire cherub was a personal favourite. pic.twitter.com/3LNDshIdt8

— Amy Burge (@dramyburge) 17 September 2016