Since the concern of commercial media is to exploit as wide an audience as possible, their repertoire of genres in any period tends to be broad and various, covering a wide (though not all-inclusive) range of themes, subjects, and public concerns. Within the structured marketplace of myths, the continuity and persistence of particular genres may be seen as keys to identifying the culture's deepest and most persistent concerns. (Slotkin 8)

Some fictions make their views of these concerns rather more explicit than others. Thomas Dixon Jr.'s The Leopard's Spots (1902) and The Clansman (1904) are extreme examples. In the former

Dixon sought, in part, to correct what he perceived as gross misrepresentations of the South in literary works, primarily in Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin, which even fifty years after its publication was still widely read. In his fictional portrayal of the beginning of the Klan, Dixon argues the group began as a defensive organization—to protect white womanhood from black male sexual aggression and to protect government from corruption. Dixon seamlessly weaves his racist rhetoric into sentimental love plots, priming readers to feel sympathy for white supremacist leaders. ("Controversial")

One of these is

Dixon's hero, Gaston [...]. Although Gaston's cause is originally southern, [...] Gaston's revenge produces a movement that finally awakens northerners to the Black menace: "You cannot build in a Democracy a nation inside a nation of two antagonistic races. The future American must be an Anglo-Saxon or a Mulatto." (Slotkin 187)

It seems a particularly gratifying context in which to recall the identity of the current president of the US, and to remember that

Children from racial and ethnic minorities now account for more than half the births in the US, according to estimates of the latest US census data.

Black, Hispanic, Asian and mixed-race births made up 50.4% of new arrivals in the year ending in July 2011.

It puts non-Hispanic white births in the minority for the first time. (BBC)

I'm certain these facts would not please Dixon. What I want to highlight here, though, is the fact that Dixon used "sentimental love plots" to express his beliefs. This is true not just of The Leopard's Spots but also of The Clansman, in which:

The southern male hero is more virile and attractive than his northern counterparts, and the northern heroine (Elsie Stoneman) is wooed from her infatuation with the unnatural doctrines of racial equality (espoused by her father) by her desire to love and be loved by the manly southerner. Elsie's father, the leader of the Radicals, is physically deformed, with "explains" his hatred of the healthy southern male and his desire to cripple and deform the southern race through miscegenation. (Slotkin 188)

I wouldn't go so far as to say that Meljean Brook's Riveted is a direct response from the romance genre to Dixon, but in her acknowledgments Brook pays tribute to

Monica Jackson, who fought to turn the world around: You flipped some of us. I truly believe that everyone else will follow, someday. I just wish that you were here to see it.

Monica, who died in May 2012, was outspoken about the racism in romance:

I've written many words on why black racial separation is so prevalent in romance. My favorite theory is that it's the nature of the romance genre. Romance is fantasy-based. Readers are notoriously picky about their settings and having sympathetic characters that they can relate to them. Also, majority romance readers have plenty of romance novels to choose. There's no shortage of books, so why should a reader take the trouble to venture outside their comfort zone and spend money on something that may not appeal? No black romance author gets major buzz in the majority romance community compared with the buzz, awards and recognition white authors receive, so where do they start?

These are a few of the reasons, but figuring out how to address the issue of segregation in romance and thinking about how to go about changing it, is a daunting task. Race is an uncomfortable and taboo subject to discuss on nearly any level by almost anybody, black or white. Desegregating any institution in this country has always been a monumental struggle. (All About Romance)

I think Brook's Riveted can be read as her small contribution to that struggle, and one which she extends so that it also challenges discrimination on the basis of gender, disability and sexual orientation. The novel suggests that it is because of prejudice that "it is not usually what we think of ourselves that makes our lives harder or easier; too often, it is what others think of you" (267).

Jackie C. Horne has argued that the novel "proves not to be a meditation on gender roles, for Brook takes for granted the equality of the sexes that Gilman and feminists in the 1960s and 70s could only imagine." This is largely true, because the heroine of the novel comes from an all-female society and works as an engineer on an airship captained by a woman. However, the "New World" is rife with sexism: in Manhattan City, for example, "exposing a bare ankle or elbow earned a rebuke and a trip in a paddy wagon back to the port's gates, where her salacious behavior was reported to Captain Vashon and the airship threatened with docking sanctions" (4). There:

without a man's name behind hers, a woman had very little. Even many of the female scientists [...] had to secure the approval of their husbands or fathers before pursuing their chosen field, and were sometimes forced to abandon that pursuit when other demands were made of them. There were exceptions, of course - there were always exceptions - but it was a sobering realization. (276)

One could make the case that, to an even greater extent, Riveted "proves not to be a meditation on race." Certainly Annika, the heroine, is "marked [...] by the darkness of her skin" (13) and although she doesn't know who her biological parents were, it's possible that she is "a descendant of the Africans who'd fled across the ocean to escape the Horde" (55). David, the hero, is half "native" (154):

Many of my father's people were among those who converted when the Europeans first came. My name - Kentewess - identifies me as one. When I was a boy living in the east, reclaiming of the old ways had just begun, so I didn't think of it much. But when we moved to the mountain builders' city [...], many of those around us took great pride in never having converted, never having lost history to Europeans. And when I was with the other boys, I would do everything I could to avoid mentioning my name, and gave them instead the name of an ancestor. I'd ask my father for legends, for tales - not even to truly honor them, but because knowing them make it easier to not feel ... European. (155)

Racial differences are noted, then, and do have an impact on how the characters are perceived, but what more often seems to set Annika apart are her colourful clothes and her "lack of proper sensibilities" (61). With David what mostly sets him apart are his prosthetics. He has a prosthetic hand "grafted on so that the steel contraption had become a working part of his body" (11), "mechanical legs" (23) and "Pale scars raked the left side of his face, with several wide, ragged stripes running diagonally from forehead to cheek [...] And [...] some sort of optical contraption [...] had been embedded into his temple, which shielded his left eye with a dark, reflective lens" (12). It sets him apart from others and at eighteen he'd "confused loving [...] with being grateful that someone would touch him without disgust" (121-22), only to discover that "she'd loved him for what he couldn't do, not what he could" (122). Years later, David knows that

There would always be the Emilys who kissed him out of pity, the women who flinched away in disgust. There would always be those with good intentions. It made David more grateful for rare men like Dooley, who took him as he was - and for women like Annika, who seemed to. (122)

Another possible response to disability, and the one expressed by the villain of the novel, is to use the disabled as an inspiration:

"Men like him [i.e. David] have had to fight harder than all of us, every day [...] It should be a lesson to the rest of us, to remember how our lives could be much more difficult. We need to be thankful for what we have [...]."

[...] David didn't want to be a hero, or a lesson. Just a goddamn man. People treating him like less or more than one made his life more difficult than losing his legs ever had. (145)

David's mother came from Hannasvick, a secret Islandic village populated only by women but since a

community couldn't continue without children, [...] some women left to lie with men, and returned with a girl - or empty-handed, if the baby had been a boy that they left with his father. Some of the women remained away, choosing to stay with their sons. Others, like Annika's mother, took in a child stolen from Horde territories or the New World. (97)

This, however, is not the reason why Annika believes that the village must remain a secret, even from David:

Annika had seen what would happen to her people if the New World descended on them. She'd seen men hanged for less than what the women had done for years. She would never expose them to the ugliest part of the New World, the part that transformed love into sickness and sin.

Not everyone in the New World believed the same; perhaps David Kentewess wouldn't, either. If she told him about the love shared between her mother and his aunt, about so many of the others who'd made their lives together in her village, maybe he wouldn't show the same disgust. But Annika couldn't know how he would react. (101-102)

It is, however, someone else who states that "Something is wrong in them, Annika, and what you see isn't love. It's just lust" (175). Annika argues with this individual but since Annika herself has never found "a woman who stirred her passion [...] - and she hadn't met any men to do it, either. Until David" (163), in our world she would probably be classified as an "ally" of lesbian, gay and bisexual people rather than as someone who was herself lesbian or bisexual. Annika herself wonders about the extent to which she is committed to being an "ally" for although she believes she would be willing to defend her lesbian or bisexual friends and relatives if their lives were at risk, she is less sure she would risk her own life

"[...] For something [...] I think it's harder to die for something you believe in. To stand up and to say that something else is wrong. I said it to my friend, but would I shout it aboard this ship? I don't know. I'd be too afraid of what would happen to me, because so many think as she does. I hate myself for this."

"When you're surrounded by stupidity, self-preservation isn't a sin."

"Refusing to challenge that stupidity and letting it continue might end up hurting someone you love, later. I'd die to protect them, but not to tell people that I've kissed a woman, too?"

Alarmed, David shook his head. Though he agreed with her in principle, he'd be the first to knock her off the pulpit if she intended to shout it from the deck. If she intended to risk herself, to stand for her people, he'd be there with her - but there had to be better ways of going about it. (180-81)

The question of how to "go about it" is raised again, this time in the context of poverty, and David argues that

"If you broke every stupid rule in the New World simply because it was stupid, you'd never have time for anything else."

"I should choose one or two that matter, then." Though she wore a faint smile, her gaze remained serious. "If I had been caught [giving money to the starving so that they could buy some food], died for it - perhaps someone would realize how stupid it is to die for a few coins. If enough people recognized it, they could make a change. But I didn't risk anything. And when I was stopped by the port officer, I thought, Who would come help me? I wouldn't even risk giving money to the hungry. [...]" (182)

Later in the novel Annika does take a risk to free others, and it does indeed "make a change." Her question, "Who would come help me?" reminds me of pastor Martin Niemöller's statement which exists in various versions: he "may have thought first of the Communists, then the disabled, then Jews, and finally countries conquered by Germany" (Marcuse) but the version which, according to Wikipedia, is most commonly cited in the US, is:

First they came for the socialists,

and I didn't speak out because I wasn't a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists,

and I didn't speak out because I wasn't a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews,

and I didn't speak out because I wasn't a Jew.

Then they came for me,

and there was no one left to speak for me. (Wikipedia)

Riveted may speak out more loudly on some issues than on others, but it seems to imply that all of us need to speak out against prejudice. Firstly, because it's the right thing to do, but also because all of us may one day face prejudice: as Annika suggests, "I suppose there is always something to make us different. I wonder if anyone at all ever feels at home" (314). As Annika and her mother acknowledge:

"It won't be easy, rabbit."

"No. It will take a long time, I think. But we can start small, here. And never back down." (388)

------

BBC. "Non-Hispanic US White Births Now the Minority in US." 17 May 2012.

Brook, Meljean. Riveted. London: Penguin, 2012.

"Controversial History: Thomas Dixon and the Klan Trilogy." Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004.

Horne, Jackie C. "Lesbiian Allies, Heterosexual Romance: Meljean Brook's Riveted." Romance Novels for Feminists. 20 Nov. 2012.

Jackson, Monica. "What It's Like." Section of "Racism in Romance?" ed. Laurie Gold. All About Romance. 15 Oct. 2005.

Marcuse, Harold. "Martin Niemöller's famous quotation: 'First they came for the Communists ...' What did Niemoeller himself say? Which groups did he name? In what order?" Webpage created 12 Sept. 2000 and last updated 24 Feb 2012.

Slotkin, Richard. Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America. 1992. New York: HarperPerennial, 1993.

-----

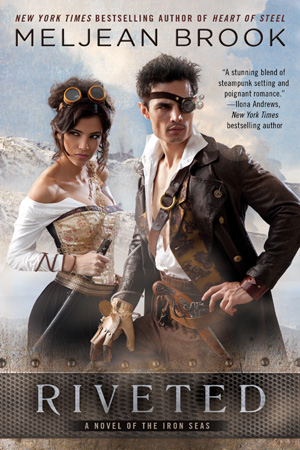

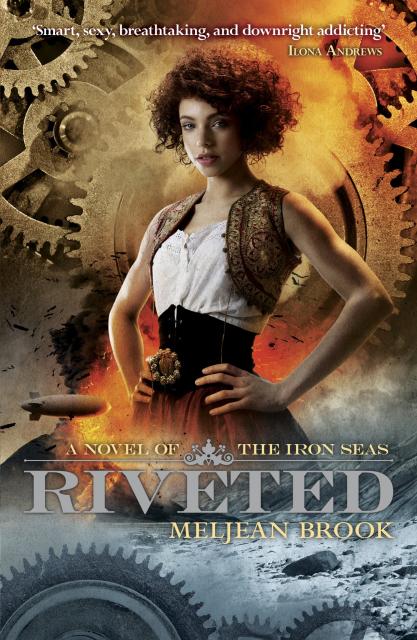

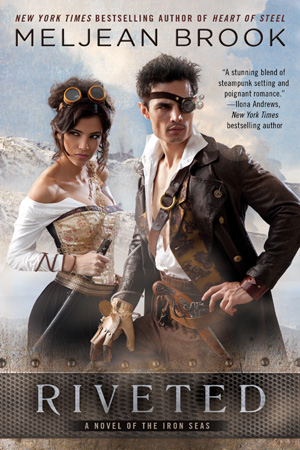

The cover image on the left (showing David as well as Annika) is the US version. The one on the right is of the UK cover. Brook has written that:

Cover art matching the contents is always iffy, unfortunately. And I think the girl on the cover [of the US edition] is darker, but the lighting/ice ends up washing her out. I saw some of the original stills from the photo shoot, and she was more obviously not-white, which was pretty awesomely thrilling. So I think the model was good. Then desaturation and lighting was added to make it look like they were on location, and then end result was all-over lighter. The UK cover ends up being closer in that respect.

This Wednesday (21 June) I'll be giving a video presentation to a conference in the Canary Islands. My paper takes Meljean Brook's Riveted as a starting point for taking a look at changing attitudes towards "otherness" in popular romance fiction. I've

This Wednesday (21 June) I'll be giving a video presentation to a conference in the Canary Islands. My paper takes Meljean Brook's Riveted as a starting point for taking a look at changing attitudes towards "otherness" in popular romance fiction. I've

ia Cheyne's "research focuses on representations of disability and illness in fiction, especially popular genres such as science fiction, romance, horror and crime" and

ia Cheyne's "research focuses on representations of disability and illness in fiction, especially popular genres such as science fiction, romance, horror and crime" and  In Zorzi's case, the barriers relate primarily to his size but Anthony is restricted by his low social class and Amoret by her gender. Indeed, in the first book in the series Amoret is only able to participate in the adventure as a result of dressing as a boy. Thinking about these differing barriers in the light of the social model of disability reminded me of Aristotle's ideas about women:

In Zorzi's case, the barriers relate primarily to his size but Anthony is restricted by his low social class and Amoret by her gender. Indeed, in the first book in the series Amoret is only able to participate in the adventure as a result of dressing as a boy. Thinking about these differing barriers in the light of the social model of disability reminded me of Aristotle's ideas about women:

I've been reading Anne Cranny-Francis's Feminist Fiction: Feminist Uses of Generic Fiction (1990). In it she defends genre fiction, whose

I've been reading Anne Cranny-Francis's Feminist Fiction: Feminist Uses of Generic Fiction (1990). In it she defends genre fiction, whose Given that romances always feature "individuals falling in love and struggling to make the relationship work" who "are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love" (

Given that romances always feature "individuals falling in love and struggling to make the relationship work" who "are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love" (