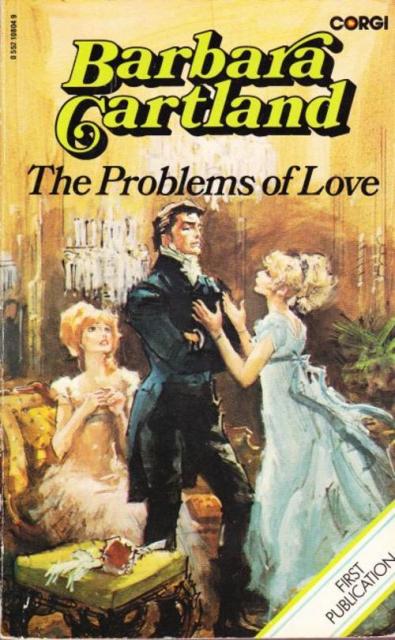

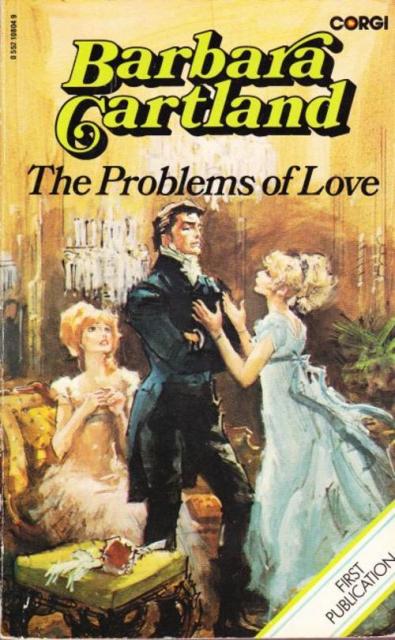

When the Romantic Novelists' Association was inaugurated in January 1960, Barbara Cartland was one of two Vice Presidents and she

When the Romantic Novelists' Association was inaugurated in January 1960, Barbara Cartland was one of two Vice Presidents and she

was the biggest personality ever in the Romantic Novelists' Association, even though she was only a member for six years. She was undoubtedly a major force in getting it off the ground and recruiting founder members. But over the years she has also presented a problem, with which the Association still grapples today: that carefully crafted image of hers has been accepted universally as the archetypal romantic novelist. (Haddon & Pearson 22)

Rosalind Brunt, for example, while acknowledging that Cartland "cannot be understood in terms of a norm or an average [...] would suggest that Cartland is 'typical' in the sense of embodying certain features that are 'characteristic' of romance" (127). Cartland's novels certainly provide some very clear examples of what Kyra Kramer and I have termed

the “alchemical” model of romantic relationships, [in which] the heroine’s socio-sexual body (her Glittery HooHa) attracts, and ensures the monogamy of, the hero’s socio-sexual body (his Mighty Wang), allowing the heroine’s socio-political body (her Prism) to focus, and benefit from, the attributes of the hero’s socio-political body (his Phallus).

This is a model she would have encountered in her own reading of romantic fiction when still a schoolgirl because she

read voraciously - dozens and dozens of light romantic novels: Elinor Glyn, E. M. Hull, whose book The Sheik had set Edwardian womanhood aquiver with dreams of an illicit passion for a desert lover, and the Queen of all romantic lady novelists, Ethel M. Dell. [...] she is insistent on the debt she owes to Ethel M. Dell, a prolific and almost totally forgotten author.

I have copied her formula all my life. What she said was a revelation - that men were strong, silent, passionate heroes. And really my whole life has been geared to that. She believed, and I believed, that a woman, in order to be a good woman, was pure and innocent, and that God always answered her prayers, sooner or later.

There was a further lesson Barbara learned from Miss Dell [...]. It was [...] the belief, as she has put it, that 'human passions are transformed by love into the spiritual and become part of the divine'. (Cloud 31-32)

Consequently, Cartland's own works of fiction

speak with mystical and transcendental accents of romance as a means to spiritual enlightenment. [...] In her many novels, Cartland promoted what she referred to as a “religion of love,” a concept she explained as a theo-philosophical concept in her many non-fictional books. The myth that Cartland cultivated in her novels was that we are saved from our material-physical prison by love. (Rix)

While Dell influenced the content of Cartland's novels, their style would appear to owe much to Lord Beaverbrook, the proprietor of the Daily Express and the Evening Standard, who took her as a protégée:

'Max taught me to write,' she says. 'I believe it is entirely due to him that I have been so successful with my books and the thousands of articles I have done over the years.' [...] she would take her Express and Standard paragraphs to the Hyde Park Hotel where Beaverbrook maintained a phone-filled office. There he would make a great performance of cross-questioning her about what she had written, then pulling her article into little pieces and crossing out the superfluities until finally he applied the proprietorial initials of approval and the authorised version went off to the paper for automatic inclusion.

The trouble, of course, was that Beaverbrook's idea of how to write was highly individual. He liked opinions expressed with certainty in short paragraphs, short sentences and short words. This was a fine formula for popular newspapers but not, alas, for great literature. The Beaver's influence is easily detected in Barbara Cartland's romantic fiction and I am not at all convinced that the influence is wholly benign. (Heald 45-46)

She herself, though, does not seem to have aspired to writing "great literature." When Tim Heald began the process of writing about her, he told Cartland he'd

better get down to some hard reading. She agreed that I must look at her four autobiographies but when I touched on the estimated 575 novels she said, quite rattily, 'Oh, you don't want to read them - they're all the same.' I said nothing to this, but thought, privately, that this was the sort of judgement made by her enemies. It was not what she herself was supposed to say. (14-15)

When asked by another biographer, Henry Cloud, about her heroines, she responded "Oh, she is always me, and always virginal of course. She's something of a Cinderella" (14). Her son, Ian McCorquodale, who became responsible for marketing the novels,concurred with her about this: he "maintains that all his mother's novels are variations on the Cinderella theme" (Heald 47). Heald's

impression is that while she would defend her work on grounds of style, accuracy of research and detail, and general all-round professionalism she acknowledges, within her own circle, that they are merely artefacts designed to give wholesome, harmless pleasure to what in a former age would have been servants and shop girls. (193-94)

Heald doesn't wholly disagree with Cartland's assessment of her work but he notes that she didn't write "her first historical romance [...] Hazard of Hearts" (129)

until 1948 [...]. She was a mature woman of forty-seven who had been writing novels for a quarter of a century before she suddenly hit on the formula which was to make her world famous. (130)

and it was, furthermore, only in the 1970s that

she really slipped into gear and started to churn them out at the prodigious rate she has maintained into her nineties [...] The popular conception is that all her books are historical romances yet this is far from the truth. Earlier novels were different. Jigsaw, the very first, was set in Mayfair, the world she knew best. [...] Later novels also took place in contemporary settings and some took themselves surprisingly seriously. None did so more than Sleeping Swords published in 1942 under her married name. The Daily Telegraph described it as 'long, serious' and 'well done'; the Manchester Guardian opined that she had adopted a 'Wells formula' and given us a 'socio-political novel, this time concerned with the last four decades of English history'.

I don't think that anyone, then or now, would claim that Sleeping Swords was a great novel but it had aspirations to genuine seriousness. (Heald 201-03)

Cloud, though, thought Cartland was also serious about her later novels:

She believes implicitly in what she writes, and this is the key to their success, the vital quality she shares with every really big, mass-selling author of popular fiction - sincerity. It is impossible to conterfeit and pointless to deride. Edgar Wallace had it, so did Ian Fleming, so does Barbara - the ability to turn their private dreams into the sort of myth that has a universal appeal. (16)

Not quite universal, I think, but certainly one that found a worldwide market.

----

Brunt, Rosalind. "A Career in Love: The Romantic World of Barbara Cartland." Popular Fiction and Social Change. Ed. Christopher Pawling. London: Macmillan, 1984. 127-156.

Cloud, Henry. Barbara Cartland: Crusader in Pink. 1979. London: Pan, 1981.

Haddon, Jenny & Diane Pearson. Fabulous at Fifty: Recollections of the Romantic Novelists' Association 1960-2010. RNA, 2010.

Heald, Tim. A Life of Love: Barbara Cartland. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1994.

- Rix, Robert W. '“Love in the Clouds”: Barbara Cartland's Religious Romances." The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 21.2 (2009).

Vivanco, Laura and Kyra Kramer. "There Are Six Bodies in This Relationship: An Anthropological Approach to the Romance Genre." Journal of Popular Romance Studies 1.1 (2010).

We've finally moved into our new home and, much as there are still quite a lot of boxes to unpack, there are quite a lot of long-neglected emails in my inbox. One of them pointed me to Sigrid Cordell's "Loving in Plain Sight: Amish Romance Novels as Evangelical Gothic." I'm hoping it'll inspire me to get back down to work again after my long break because, in her introduction, she gives some reasons why it's worth studying romance novels:

We've finally moved into our new home and, much as there are still quite a lot of boxes to unpack, there are quite a lot of long-neglected emails in my inbox. One of them pointed me to Sigrid Cordell's "Loving in Plain Sight: Amish Romance Novels as Evangelical Gothic." I'm hoping it'll inspire me to get back down to work again after my long break because, in her introduction, she gives some reasons why it's worth studying romance novels:

When the Romantic Novelists' Association was inaugurated in January 1960, Barbara Cartland was one of two Vice Presidents and she

When the Romantic Novelists' Association was inaugurated in January 1960, Barbara Cartland was one of two Vice Presidents and she I'm probably going to be moving house soon, which means I'll have to part with quite a few of my books. I'm treating this as an opportunity to take a break from my current project and concentrate on books I've been meaning to read for a while; one of them is Amanda Vickery's The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England (there's a detailed review

I'm probably going to be moving house soon, which means I'll have to part with quite a few of my books. I'm treating this as an opportunity to take a break from my current project and concentrate on books I've been meaning to read for a while; one of them is Amanda Vickery's The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England (there's a detailed review

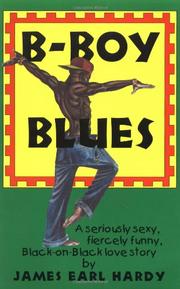

In “What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?”: Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel," Marlon B. Ross states that

In “What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?”: Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel," Marlon B. Ross states that Mate Selection: "Mr Collins meant to choose one of the daughters" (illustration by Hugh Thomson,

Mate Selection: "Mr Collins meant to choose one of the daughters" (illustration by Hugh Thomson,