I was sent a copy of Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen (ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr) around Christmas but I waited till after New Year to take a closer look at it. It's not about envying the Virgin Mary, although her presence does make itself felt particularly in the final chapter.

I was sent a copy of Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen (ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr) around Christmas but I waited till after New Year to take a closer look at it. It's not about envying the Virgin Mary, although her presence does make itself felt particularly in the final chapter.

The editors suggest that "our ideas about virginity - the hymen in particular - and the phallus are 'cultural fantasies' that continue to inspire, provoke, and unsettle us" (2): the first and second essays in the volume show the continuities across the centuries of some of these "cultural fantasies". And yet:

As we began to discuss virginity, however, we realized that many of these common virginal narratives are not true. Virginity extends well beyond the girl who protects herself and her hymen until marriage. [...] Indeed, insistence on the hymen erases all kinds of bodies save the most normative, cisgendered body of the female. Therefore, it is imperative that we go beyond the hymen and think about virginity without it. Truth be told, boys are virgins, queers are virgins, some people reclaim their virginities, and others reject virginity from the get go. (4-5)

The editors have tried to ensure that the collection of essays in the volume have a wide range but "as editors regret that this collection does not contain much about lesbian or trans virginities - important areas of research that need to be attended to [...]. It is surprising that, though virginity studies is a field dominated by the idea that virginity is female, lesbian experiences of virginity are unaccounted for in the scholarship" (11). There is a discussion of Catalina de Erauso, though, in the last chapter.

I've copied out the abstracts of the two chapters on romance in this post so here I'll just highlight a few other quotes/elements which piqued my interest, mainly relating to depictions of race/ethnicity/geography and religion in texts/contexts related to popular romance fiction.

Chapter 1: "I Will Cut Myself and Smear Blood on the Sheet": Testing Virginity in Medieval and Modern Orientalist Romance [by Amy Burge, pages 17-44.]

Amy Burge's

focus throughout is on the [virginity] test as it applies to women, echoing the deeply gendered discourses that surround virginity testing: there are no virgin sheikhs. (18)

I'm kind of tempted to look for one now, just in case he exists out there somewhere. Almost certainly not published by Harlequin Mills & Boon, though, as I know Amy researched those very, very carefully.

Given the popularity of virgin heroines in romance fiction, it's really interesting to note that her

large-scale analysis of Mills & Boon Modern Romance [i.e. the line known as Harlequin Presents in the North American market] novels reveals that female virginity is particularly pronounced in romance novels with "foreign heroes": the ubiquitous Greeks, Italians, Spaniards, Brazilians, Argentines, and, of course, sheikhs. Of the 931 Modern Romance novels published in the United Kingdom from 2000 to 2009, 458 feature virgin heroines, and 281 of them (approximately 61 percent) have foreign heroes. This simultaneously reveals Western preoccupation with virginity and its situating of it "elsewhere." (21)

This does begin to make me wonder if, among English-speaking writers and readers, Greece, Italy and Spain are in some way not considered part of the "West," and in turn reminds me of Hsu-Ming Teo's essay about Rudolph Valentino playing the part of the "sheik." Teo mentions that

the period of mass European immigration from the 1840s to 1924 [in the US] “witnessed a fracturing of whiteness into a hierarchy of plural and scientifically determined white races,” dominated by Anglo-Saxons. [...] To southern Americans, the Mediterranean, Eastern European, Jewish, and Levantine immigrants were “in-betweens,” occupying a status between true whites and blacks."

Something of that hierarchy perhaps continues to haunt romance fiction; as a result of my own research on Greece in popular romance (forthcoming) I came across the suggestion that in England the Mediterrean has been particularly associated with passion since at least the early modern period.

It isn't entirely clear why cultures assumed to be more passionate should also be assumed to value virginity more highly but it is certainly stressed in romance novels set in the "romance East" that "female virginity is of great cultural importance. Sheikh romances repeatedly highlight the importance placed on virginity in Eastern culture [...]. Such a cultural valuing is connected to ideas of tradition often glossed as 'medieval.'" (Burge 23). As Burge concludes:

For contemporary popular romance fiction to construct the "romance East" as a space in which "medieval" virginity can be celebrated echoes the similar practice of situating practices or attitudes inappropriate today - such as sexual violence - in a distant space, such as the historical past or, indeed, the East. Relegating the valuing and testing of virginity to the East might be in line with current popular ideas about the East, but it also reveals some of the romance genre's motivations for situating this valuing in the fictional romance East. In other words, for the romance genre to celebrate the unequal traditions of heteronormativity, the virginity testing that upholds these traditions must be situated "elsewhere." As much as many Western readers [...] might condemn "foreign" cultures for continuing to conduct virginity tests, the gender hegemony that these tests uphold is clearly evident and even celebrated in our own romantic cultural imagination, as revealed in the pages of some of the most popular contemporary Western fiction. (34-35)

Chapter 2: Between Pleasure and Pain: The Textual Politics of the Hymen [by Jodi McAlister, pages 45-64.

Given the way in which the valuing of virginity is located "elsewhere" in the popular romances examined by Burge, it's intriguing that McAlister observes that

in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries [..] Some virgins were said to be affected by chlorosis or "green-sickness," for which marriage was recommended as the cure [...]. We can see this represented in [...] the 1682 ballad "A Remedy for the Green Sickness" [...] We can see represented here not only the cure for green-sickness but also the pathologization of maintained virginity that existed during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Hanne Blank notes that it is an interesting coincidence that green-sickness was so often diagnosed during the period in which Protestantism, with its emphasis on marriage as the ideal state, became popular in Europe. (47-48)

Is it also a coincidence that the countries/places onto which romance novels seem to project the idealisation of virginity are not Protestant? Possibly it is, but at the same time I can't help but remember that in the seventeenth century:

European writers associated Islam with, and criticized it for, excessive and depraved sexual practices. The sexual excesses of Muslims were believed to derive from their religion, which permitted polygamy. (Teo, Desert 40-41)

A couple of centuries later, Gothic fiction linked Catholicism and "depraved" sexuality. For example:

When in The Monk (1796), Matthew G. Lewis uses the details of conventual life to suggest lurid forms of sexual excess such as necromancy, incest, matricide, and same-sex love, he does not need to explain his choice of a Catholic setting, a Mediterranean country (Spain, not Italy in this case), or religious life itself. All these things, to the English imagination at least, make such easy, rational sense that Lewis could assume a general understanding of (and even assent to) his extravagant posturing. And while reviewers criticized Lewis’s excess, they never suggested that his portrayal of Catholic monastic life was inappropriate. If the novel can be considered sensational, that is not because anyone objected to the portrayal of the characters themselves: oversexed and violent Catholic priests, victimizing and vindictive nuns, devil worship and self-abuse. These and other lurid sexual possibilities were common popular perceptions of conventual life in Mediterranean countries. (Haggerty)

Is it yet another coincidence that all this sexual excess is taking place in settings which are supposed to be filled with virgins?

Chapter 3 - The Politics of Virginity and Abstinence in the Twilight Saga [by Jonathan A. Allan and Cristina Santos, pages 67-96.

Edward, the virgin hero of the Twilight saga is "foreign" in a different way from Mediterranean romance heroes: he is a vampire. Again, there is a link to religion:

Silver argues that his values are "uncommon in popular, mainstream secular discourse about young adult sexuality today." [...] there is an entire industry dedicated to ensuring sexual purity, which though having a religious affiliation, is also very much a part of secular culture. (72)

The issue of virginity in US culture is also mentioned in the next chapter.

Chapter 4 - Lady of Perpetual Virginity: Jessica's Presence in True Blood [Janice Zehentbauer and Cristina Santos, pages 97-123.]

Certainly, in the past two decades in America, evangelical church groups and the American government have united to encourage youth in general, and young women in particular, to choose abstinence [...]. Historian and independent scholar Hanne Blank points out that, "of all the developed world, the United States is the only one that has to date created a federal agenda having specifically to do with the virginity of its citizens." (97)

Zehentbauer and Santos suggest that

Twenty-first-century America's obsession with virginity also emerges in many artifacts of popular culture, especially those of the gothic or supernatural genres. In her influential Our Vampires, Ourselves, Nina Auerbach argues that vampires, in the Anglo-American cultural imaginary, embody and signify the sociopolitical concerns of the era that produces them. (98)

If the US policies around virginity have been at all divisive, and it would seem that they have, given that "repealing abstinence-only programs, much less authorizing the full scope of reproductive health care services, runs into deep moral divides" (Morone and Ehlke 318), and if Edward's values "are 'uncommon in [...] secular discourse," could it be that those values have to be translated into a "foreign" (in this case vampiric) context to make them palatable to a mass audience which is, nonetheless, still fascinated by virginity and what it represents?

-----

The other chapters in the volume are:

McGuiness, Kevin. "The Queer Saint: Male Virginity in Derek Jarman's Sebastiane." (127-143.)

Ncube, Gibson. "Troping Boyishness, Effeminacy, and Masculine Queer Virginity: Abdellah Taïa and Eyet-Chékib Djaziri." (145-169.)

Sayed, Asma. "Bollywood Virgins: Diachronic Flirtations with Indian Womanhood." (173-190.)

Crowe Morey, Tracy and Adriana Spahr. "The Policing of Viragos and other "Fuckable" Bodies: Virginity as Performance in Latin America." (191-231.)

That last chapter introduced me to Catalina de Erauso whose life

reads like a picaresque novel. Born, probably in 1592, to a noble Basque family in San Sebastián, Spain, she bolted from a convent before taking her vows, assumed masculine clothing, gave herself a new identity as "Francisco de Loyola," and, early in the seventeenth century , made her way to the New World, where she led the rough-and-ready life of a soldier in the Spanish colonies.

On the battlefield she was a formidable warrior; in her other exploits she gambled, engaged in dalliances with women, brawled, and faced death sentences for murder. Once her true sex was revealed, she became a celebrity in Spain. [...]

In her memoir Erauso stressed her chief virtues as a man--physical courage--and as a woman--virginity . While she did not stint at recounting transgressive acts of "manly" bravery such as fights resulting in murder, she was more oblique when referring to acts that were sexually transgressive.

At no point does Erauso speak of physical attraction to a man. She did, however, include several incidents that show her affection for women. (Rapp)

As the authors note, she fared much better than either Joan of Arc or more modern women whose soldiering/other forms of political engagement was responded to with state-sponsored violence that included rape and execution.

-----

-

- Allan, Jonathan A. and Cristina Santos, 2016.

- "The Politics of Virginity and Abstinence in the Twilight Saga." Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen. Ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr. London: Zed. 67-96.

- Burge, Amy, 2016.

- "‘I Will Cut Myself and Smear Blood on the Sheet’: Testing Virginity in Medieval and Modern Orientalist Romance." Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen. Ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr. London: Zed. 17-44.

- Haggerty, George. 2004-2005.

- "The Horrors of Catholicism: Religion and Sexuality in Gothic Fiction." Romanticism on the Net 36-37.

- McAlister, Jodi, 2016.

- "Between Pleasure and Pain: The Textual Politics of the Hymen." Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen. Ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr. London: Zed. 45-64.

-

- Morone, James A. and Daniel C. Ehlke, 2013.

- Health Politics and Policy. Fifth Edition. Cengage.

- Rapp. Linda. 2003.

- "Erauso, Catalina de (ca 1592- ca 1650)." glbtq Encyclopedia.

- Teo, Hsu-Ming, 2010.

- 'Historicizing The Sheik: Comparisons of the British Novel and the American Film', Journal of Popular Romance Studies 1.1.

- Teo, Hsu-Ming. 2012.

- Desert passions: Orientalism and romance novels. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Zehentbauer, Janice and Cristina Santos, 2016.

- "Lady of Perpetual Virginity: Jessica's Presence in True Blood." Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen. Ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr. London: Zed. 97-123.

-

.preview.jpg)

I was sent a copy of Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen (ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr) around Christmas but I waited till after New Year to take a closer look at it. It's not about envying the Virgin Mary, although her presence does make itself felt particularly in the final chapter.

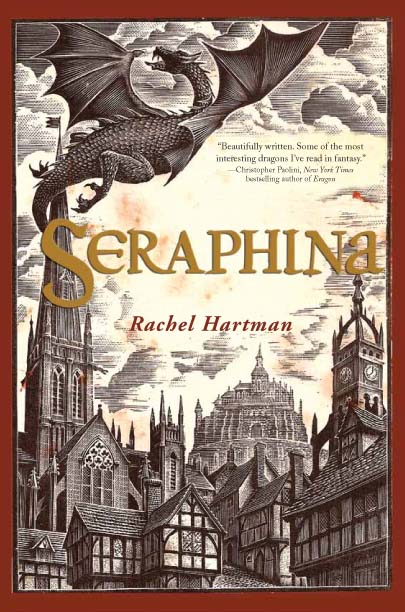

I was sent a copy of Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen (ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr) around Christmas but I waited till after New Year to take a closer look at it. It's not about envying the Virgin Mary, although her presence does make itself felt particularly in the final chapter. I'd have identified it as a fantasy version of the late Middle Ages, but that's probably because in the Castilian context the fifteenth century is considered medieval. Random House describe the novel as being set in "an alternative-medieval world" and, although I'm no expert on this, the buildings on the cover look

I'd have identified it as a fantasy version of the late Middle Ages, but that's probably because in the Castilian context the fifteenth century is considered medieval. Random House describe the novel as being set in "an alternative-medieval world" and, although I'm no expert on this, the buildings on the cover look