Pillaging the Past for Contemporary Enjoyment

In Alex Beecroft's Blue Eyed Stranger (2015) one of the heroes, Martin, is a history teacher and historical reenactor whose "mother’s a Yorkshirewoman, my father’s from the Sudan" (61). Historical accuracy matters to him and so he has thought out a matching back-story for the character he enacts: "my character is from the kingdom of Meroe in Nubia, one of whose principle [sic] exports was carnelian" (32);

A fair amount of both Saxons and Vikings travelled to Rome on pilgrimage even in the time we’re reenacting, and a fair amount of Nubians travelled from the Sudan to Rome to trade in gold, ivory, and gems. No reason why a Viking couldn’t have married a merchant’s daughter while he was out there and brought her home. (61)

Archaelogical evidence certainly suggests this is a possible scenario given that

at least some people from Africa or of African descent were living and dying in rural and urban communities in the British Isles during the 'Viking Age' (eighth to eleventh centuries). (Green)

All the same, Martin, knows "he wasn’t what the public wanted to see when they looked for Vikings" (34); in many ways, the public want what they imagine the Vikings to be rather than the more complex realities of which historians are aware.

According to María José Gómez Calderón,

In the last two decades there has been a significant increase of novels of the so-called «hot historical» variety focusing on the Viking as object of feminine erotic desire. The most famous authors of these new Viking narratives, Johanna Lindsey, Catherine Coulter, and Sandra Hill have even become «New York Times Best-Sellers.» (292)

and their outlines are well-known enough to be parodied:

In Jackie Rose’s I’m a Viking and I Protest (2004), a contemporary American man of Norse origin, Karl Gustavsen, founds an antidefamation league and sues romance writer Rose Jacobson for presenting Vikings as sexy rapists in her works [...]. To begin with, Karl denounces Rose’s unfair presentation of the Viking in her best-seller Ravished by Ragnar (significantly published by Orgazm Books). (Gómez Calderón 296)

He does have a valid point when protesting against the depiction of Vikings as "sexy rapists" because, as Erika Ruth Sigurdson points out,

While eighth-century writers were quick to denounce the various crimes of Viking invaders, very few of those largely monastic writers commented on rape in the invasions—to the point that even modern scholarship has considered it possible that rape was simply not a part of Viking invasions. (253)

Despite this, the

theme of Viking rape—[which treats] rape as historicizing detail and rape as evidence of Viking masculinity-—appear[s] from the earliest incarnations of romanticized Viking narratives in the early nineteenth century and onward. (Sigurdson 252-3)

In other words, rape appears as a "historicizing detail" in "nineteenth-century Viking stories" because it "formed an integral part of scene setting and the creation of historical authenticity, of creating a world that felt authentically Viking-Age" (261). Similarly, in a collection of twelve Harlequin Mills & Boon romances reprinted in 2007 and set later in the Middle Ages,

The invented space of the Medieval Collection is one of acute sexual danger for women. [...] The threat of rape or sexual assault is an ever-present fear for medieval heroines [...]. Much of the sexual harassment in these novels originates from the hero, and although some are more explicit, most first sexual encounters are characterized by violence and male dominance. (Burge 104)

Rape in fictions set in the Middle Ages presumably felt and continues to feel authentic, even if it wasn't, because,

As Kathryn Gravdal, a leader in the field of medieval rape, explains, modern culture has developed powerful myths on the subject of rape and sexuality in the Middle Ages:

The first is the notion that women enjoyed unparalleled sexual power and freedom in the days of courtly love. The second is the converse belief that rape was commonplace in the Middle Ages because society was so barbaric that men “did not know any better.” (Gravdal 1991,152)

It is this second myth, the notion of barbaric men and rape as a commonplace[,] that is particularly prevalent in popular depictions of the Vikings. (Sigurdson 254)

Nonetheless, a propensity to rape women was presumably not considered an intrinsic, or at least a desirable, aspect of masculinity in the nineteenth century, because in most of the Viking texts produced in this period

the hero’s masculinity was defined [...] by his sexual restraint, and his ability to love a worthy woman and look for her love in return. At the same time, we have also seen a few places where violent sexuality plays a role in Viking masculine identity, particularly in the case of minor characters, or in the blurring of lines between abduction and voluntary marriage. But there are a few examples from this early period where Viking rape is treated as an unambiguously integral part of Viking masculinity. (Sigurdson 262)

As ideas about masculinity changed, however, so did the sexuality of Viking heroes and in recent decades

Vikings, with their giant battle-axes and muscular good looks, perfectly symbolize “the aggressive-passive, dominant-submissive, me-Tarzan-you-Jane nature of the relationship between the sexes in our [rape] culture” (Herman 1994, 45). With its close correlation to the broader “sex and violence,” the phrase “rape and pillage” has come to encapsulate this paradox and perfectly describe a violent, dominant form of male sexuality. (Sigurdson 250)

What I think all this demonstrates is, firstly, that historical fiction can be shaped by inaccurate ideas about the past and, secondly, that it will also tend to be shaped by contemporary ideas about gender roles and sexuality.

This pillaging of the past often enhances the enjoyment of modern readers. For example:

sexuality in the Medieval Collection is drawn from modern anxieties concerning sexual violence, but this violence is safely confined to the Middle Ages, obscuring the extent to which submission and dominance can be rooted in modernity. Furthermore, defining the medieval as a period characterized by sexual violence works oppositionally to suggest that modern sexuality is not violent. (Burge 109)

If imagined differences between past and present can bring pleasure, so too can imagined similarities. Eloisa James, for example, has argued that

we historical authors need to think more deeply about what men were like back in the era we’re writing about—and if you ask me, likely not much has changed. They were scratching themselves and boasting and carrying on generally 200 years ago.

Those might not seem at first glance like traits which would give readers enjoyment but, on reflection, I think perhaps they do for some readers because they allow the heroines (and through them some modern female readers) to feel a smug sense of superiority. To quote a secondary character in a non-Viking romance:

"Women get off on that, you know."

"What?"

"Men making jerks out of themselves, [...] I think it reinforces their sense of superiority. I mean, deep down they're ninety-nine and nine-tenths percent positive we're idiots. Still, they like to have it confirmed every once in a while." (Buck 34)

Or, to put it yet another way, there is an appeal

to what in the novels is presented as the eternal feminine that joins both females [i.e. the heroine and the female reader], [...] by assuming that women of all ages have to face the same kind of problems with men, that is, the eternal masculine. (Gómez Calderón 294)

Inaccurate depictions of the past may be enjoyable (although presumably not to those, like Martin, who crave accuracy) but they may, cumulatively, have serious consequences. For example, if one can create the impression of an "eternal feminine" one can ignore the ways in which gender roles have changed and are, therefore, socially constructed. Perhaps even more seriously,

Racist and white supremacist ideas about the past have lingered in our culture. They are not limited to dyed-in-the-wool racists or card-carrying members of the Klan. They can seem natural and normal. That makes them a fundamental part of institutionalized racism as it exists today, since the past forms and informs the foundations of the present. [...] We see the past the way it has been presented to us in school, in history books, and in popular culture. (Sturtevant)

As Martin says, being immersed in accurate history can feel

Funny and bizarre, unsettling and uncomfortable, sometimes even repellent. But you always returned from it with a refreshed perspective, so that just for a little while, before habit kicked back in, you could see your own world with a stranger’s eyes, and all the things that were normally invisible showed up like cancer cells tagged with radiant dye. (121)

It's not everyone's idea of enjoyment, and so perhaps not easy to incorporate into a mass-market genre. In addition, in popular romance fiction the readers do need to feel an emotional connection to the protagonists; that could be inhibited if readers feel too unsettled or repelled by the characters' beliefs and attitudes (though less so if those emotions are elicited by the characters' context). So there are certainly challenges involved in writing historically-accurate historical romance but there also romance authors who are willing to accept those challenges and make their depictions of history that bit more challenging to long-accepted norms.

-----

Beecroft, Alex. Blue Eyed Stranger. Hillsborough, NJ: Riptide, 2015.

Buck, Carole. Knight and Day. New York, NY: Silhouette, 1992.

Burge, Amy. “Do Knights Still Rescue Damsels in Distress?: Reimagining the Medieval in Mills & Boon Historical Romance.” The Female Figure in Contemporary Historical Fiction. Ed. Katherine Cooper and Emma Short. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. 95-114.

Gómez Calderón, María José. “Romancing the Dark Ages: The Viking Hero in Sentimental Narrative.” Boletín Millares Carlo 26 (2007): 287-97. [Available in full, for free, online.]

Green, Caitlin. "A great host of captives? A note on Vikings in Morocco and Africans in early medieval Ireland & Britain." 12 September 2015.

James, Eloisa. "Making Rakes from Real Men." The Popular Romance Project. 9 April 2013. [link to the Internet Archive]

Sigurdson, Erika Ruth. "Violence and Historical Authenticity: Rape (and Pillage) in Popular Viking Fiction." Scandinavian Studies 86.3 (2014): 249-67.

Sturtevant, Paul E. "Race, Racism, and the Middle Ages: Tearing Down the 'Whites Only' Medieval World." The Public Medievalist. 7 February 2017.

I was sent a copy of Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen (ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr) around Christmas but I waited till after New Year to take a closer look at it. It's not about envying the Virgin Mary, although her presence does make itself felt particularly in the final chapter.

I was sent a copy of Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen (ed. Jonathan A. Allan, Cristina Santos, and Adriana Spahr) around Christmas but I waited till after New Year to take a closer look at it. It's not about envying the Virgin Mary, although her presence does make itself felt particularly in the final chapter.

Katherine E. Morrissey's

Katherine E. Morrissey's

I'm probably going to be moving house soon, which means I'll have to part with quite a few of my books. I'm treating this as an opportunity to take a break from my current project and concentrate on books I've been meaning to read for a while; one of them is Amanda Vickery's The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England (there's a detailed review

I'm probably going to be moving house soon, which means I'll have to part with quite a few of my books. I'm treating this as an opportunity to take a break from my current project and concentrate on books I've been meaning to read for a while; one of them is Amanda Vickery's The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England (there's a detailed review

My article about Georgette Heyer is out now in the latest issue of the Journal of Popular Romance Studies. It's called "

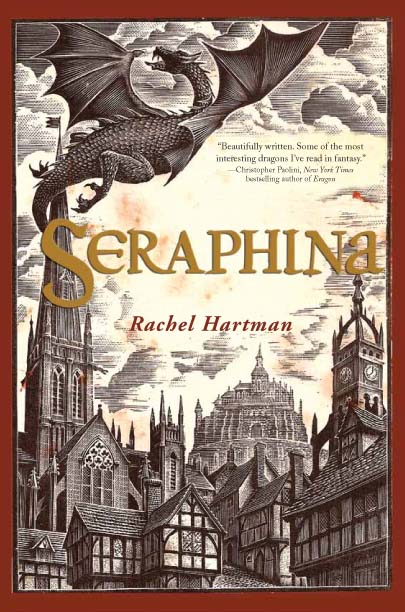

My article about Georgette Heyer is out now in the latest issue of the Journal of Popular Romance Studies. It's called " I'd have identified it as a fantasy version of the late Middle Ages, but that's probably because in the Castilian context the fifteenth century is considered medieval. Random House describe the novel as being set in "an alternative-medieval world" and, although I'm no expert on this, the buildings on the cover look

I'd have identified it as a fantasy version of the late Middle Ages, but that's probably because in the Castilian context the fifteenth century is considered medieval. Random House describe the novel as being set in "an alternative-medieval world" and, although I'm no expert on this, the buildings on the cover look