Continued from Part I and Part II. In this post I've written up my notes and comments on the final papers:

Fiona Martinez, Sheffield Hallam University - The Romance Genre & Feminism: Friends or Foes?

Lucy Sheerman, Independent Researcher - Charlotte Brontë and Contemporary Representations of Romance Fiction

Deborah Madden, University of Sheffield - Rewriting Romance in 1930s Spain and Portugal: Rebellious Heroines of Federica Montseny and Maria Lamas

Martina Vitackova, University of Pretoria - The Sexual Turn in Post-Apartheid Women's Writing in Afrikaans

Fiona Martinez, Sheffield Hallam University - The Romance Genre & Feminism: Friends or Foes?

Fiona's research focuses on:

the use of romance and the romance genre within contemporary women's literature, and the extent to which its creation of authentic relationships is a feminist endeavour. Combining Jean-Paul Sartre's interest in existential authenticity and his views on the need for authenticity within relationships I will be examining the work of Margaret Atwood, Ali Smith, Zadie Smith and Jeanette Winterson and considering the ways in which they have created representations of 'authentic love' within their literature through the re-writing of the romance genre.With Sartre’s theory, and belief that authenticity within a romantic relationship was possible, I will consider the extent to which contemporary women writers mirror this belief within their literature. I will aim to use this research to question borders between high and low culture through an exploration of the practice of romance writing by contemporary women writers and a consideration of whether the current boundaries are typical of, and help define,a contemporary female aesthetic which re-writes the romance.

Martinez (@PhFi_) discussing motherhood, the female body and heterosexual relationships in NW by Zadie Smith #CWWRomance16

— Krystina Osborne (@KrystinaOsborne) 11 June 2016

Martinez (@PhFi_) moves on to discussing the unconventional love triangle in Jeanette Winterson's Gut Symmetries #CWWRomance16

— Krystina Osborne (@KrystinaOsborne) 11 June 2016

In this paper Fiona outlined the relationships depicted in Zadie Smith's NW and Jeanette Winterson's Gut Symmetries. Fiona contrasted the same-sex relationship between women with the heterosexual ones and also looked at the pressure on women within a heterosexual relationship to have children. Fiona suggested these novels question aspects of compulsory heterosexuality and therefore differ from/re-write the romance.

I haven't read either of these novels but I wonder if they're maybe closer to some genre romances than others. For example, in Karin Kallmaker's genre romance In Every Port, one of the heroines is involved in a heterosexual relationship when she first meets the other heroine and so there is some discussion/contrasting of lesbian and heterosexual relationships. I'm not sure whether Jane Rule would have classified her Desert of the Heart as a romance but it can certainly be considered one and in it:

Evelyn thought marriage was a way to make herself a real woman, but she was unable to have children and is not sure whether she ever really loved her husband. It is her connection with Ann, finally, that puts her in touch with her femininity and all that it encompasses: "She was finding, in the miracle of her particular fall, that she was, by nature, a woman. And what a lovely thing it was to be, a woman."(After Ellen)

Some romances nowadays depict polyamorous relationships between more than two people. So there may be elements of the two novels Fiona analysed which are, in fact, present in romance novels. Maybe romance has been re-writing itself?

Lucy Sheerman, Independent Researcher - Charlotte Brontë and Contemporary Representations of Romance Fiction

Lucy is a "Writer, gripped by the legacy of the Apollo moon landings and currently at work on a fan fiction project". Her Rarefied (falling without landing) was written

in response to the documentary Apollo Wives, a series of interviews with the wives of the Apollo astronauts. They talked about the experience of being plunged into the media spotlight while their husbands were on the Apollo programme and how they formed strong bonds with each other while living in close proximity on a military housing base.

Structurally I have been using fairly strict constraints to number of lines and number of beats in a line, but these are significantly longer than the palette I used to work with. I find that it has been very liberating to lengthen my lines and it has felt like reintroducing oxygen into the writing to a degree. The ability to let the writing breathe and allow a vestige of narrative provided an entry point into the work which however I felt I could still control. Some of my earlier work had got so sparse that it was almost visual. This shift meant the text became more expansive, capable of including narrative, memory and speech in quite a different way. (Peony Moon)

Lucy's approach to the texts discussed in her paper (Jane Eyre, Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca and Fifty Shades of Grey) similarly mixed the visual and textual. In Jane Eyre fire represents passion out of control. In Brontë's own life, the passionate romances she'd read and enjoyed in the Ladies Journal were burned by her father because he disapproved of their content. In other circumstances he feared fire and therefore kept the parsonage interior rather austere so that it would be less of a fire risk. Nonetheless, her brother, Branwell, set his curtains on fire while drunk. These events may have affected Charlotte's depiction of the destruction of Thornfield Hall by Mr Rochester's wife, who has been hidden in the upper level of the house.

In Rebecca, it is again the influence of the displaced wife which causes the fire that destroys the hero's home and Lucy also noticed the way in which the narrator of Rebecca had earlier burned some text written by Rebecca.

Lucy was intrigued by the similarities between this burning, the burning of the Ladies Journal and contemporary burnings of copies of Fifty Shades of Grey.

Burning of texts/books naturally led us to discuss censorship and I was reminded of Lady Chatterley's Lover,

one the most banned books in history. Infamous for its explicit descriptions of sex and other vulgarities, it was only published openly in the United Kingdom in 1960. The book focused on the illicit affair between an upper class woman and her lower class gamekeeper, and it was received with outrage and intrigue, resulting in numerous abridged versions being published throughout the 1920's, 1930's, and 1940's. [...]

First printings were bound with brown boards with an insignia of a phoenix gracing its front cover. The phoenix has remained a potent symbol for the book, in large part because of the book's victory in the infamous British Obscenity Trial in 1960. (Biblio)

The phoenix, of course, rises from the ashes and it's been suggested that some of the fire in Jane Eyre could be read similarly as a similarly purifying/productive force:

The image of fire might symbolize signifying first sinfulness, then rebirth. Since the passionate love that Rochester and Jane first held was sinful, it was accompanied by images of fire and burning--possibly a portrait of Hell. After Jane leaves Thornfield, and her "burning" desires for Rochester are somewhat subdued, the next and final image of fire occurs. In the fire that destroyed Thornfield, Rochester proved his worthiness to Jane by attempting to save Bertha from the blaze. A feat that indicated that he had tempered his "burning" passions regarding Jane and Bertha and atoned for the wrongs that he had perpetrated on the women in his life. Shortly thereafter, Jane and Rochester reunited and each proved to be reborn. (Vaughon)

Deborah Madden, University of Sheffield - Rewriting Romance in 1930s Spain and Portugal: Rebellious Heroines of Federica Montseny and Maria Lamas

Deborah's "doctoral research seeks to identify left-of-centre Spanish and Portuguese women writers from the early decades of the twentieth century whose works have been excluded from the literary canon. By focusing on novels by politically progressive women in early twentieth-century Iberia, the thesis aims to examine how a selection of female authors used literature as a means of political expression, while uncovering the shared experiences of Iberian women."

Deborah Madden (@DMadden89) outlines the historical and political context of the work of Federica Montseny and Maria Lamas #CWWRomance16

— Krystina Osborne (@KrystinaOsborne) 11 June 2016

That context was dominated by military upheaval. In Spain a Republican government was overthrown after a Civil War which ended with the triumph of the fascists, under General Franco (in power from 1939-1975). Similarly in Portugal

the 28 May 1926 coup d'état, sometimes called 28 May Revolution or, during the period of the authoritarian Estado Novo (English: New State), the National Revolution (Portuguese: Revolução Nacional), was a military coup that put an end to the unstable Portuguese First Republic and initiated the Ditadura Nacional (National Dictatorship), later refashioned into the Estado Novo, an authoritarian dictatorship that would last until the Carnation Revolution in 1974. (Wikipedia)

Federica Montseny

was born in Madrid, Spain, on 12th February, 1905. Her parents were the co-editors of the anarchists journal, La Revista Blanca (1898-1905). In 1912 the family returned to Catalonia and farmed land just outside Barcelona. Later they established a company that specialized in publishing libertarian literature.

Montseny joined the anarchist labour union, National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT). As well as working in the family publishing business she contributed articles to anarchist journals such as Solidaridad Obrera, Tierra y Libertad and Nueva Senda. In her writings Montseny called for women's emancipation in Spain. [...]

In November 1936 Francisco Largo Caballero appointed Montseny as Minister of Health. In doing so, she became the first woman in Spanish history to be a cabinet minister. Over the next few months Montseny accomplished a series of reforms that included the introduction of sex education, family planning and the legalization of abortion. (Spartacus)

Heroínas, the novel by Montseny which Deborah discussed, was published around 1936, is set during a revolution and involves a heroine who has two suitors. The first is a socialist who proposes to marriage to the heroine in the event that they win the revolution because he believes she would be an asset to him in his political career. She turns him down and is rather more attracted to an anarchist who seems to embody the romantic ideal but is, however, already involved with another woman and is therefore also deemed unsuitable. Both men are executed but the heroine survives and continues the fight. [Quite a lot of pages of the novel have been put online here by Margaret Killjoy who found it at International Institute of Social History, which "is the world’s largest repository of anarchist history. Of particular note to me, it houses almost-complete collections of La Novela Ideal and La Novela Libre". Unfortunately Margaret "can’t really read enough Spanish to understand these things. So please, anyone with interest in this stuff, let me know. If the stories are good, I’d be happy to make them available in zine format. And if anyone is feeling really inspired, I’d be happy to print English translations as well." (details here)]

Maria Lamas's novel Para Além do Amor (1935) features a heroine who is unhappily trapped in a loveless marriage to a rich industrialist. She takes a lover who encourages her to work to improve the lives of the workers by setting up medical facilities for them etc. He has the opportunity to move abroad and wants them to go together but she rejects him, saying that she stays in Portugal not out of fear, or even from love for her children, but because she must continue her work.

These aren't the happy endings one would expect in a romance novel. I wondered if they could, perhaps, be thought of as romances in which the ideal partner is not another human being but a cause. Perhaps that's a bit of a stretch.

Martina Vitackova, University of Pretoria - The Sexual Turn in Post-Apartheid Women's Writing in Afrikaans

Martina's paper and current research was prompted by an article which stated that Afrikaans women's romantic fiction features active female sexual characters. While Martina thinks this is true of some women's writing in Afrikaans (for example an autobiographical account by a sex worker), she does not believe it is true of the works of a highly acclaimed author (and academic) whose novels sounded to me like "inspirational" (Christian) romance albeit with mild depictions of sexual activity. These Afrikaans heroines do have pre-marital sex and have even had previous sexual partners before they meet their heroes. However, the sexual passages in the novels are not very explicit, give the heroines rather passive roles in love-making and suggest that true sexual fullfilment can only be found with the right partner (i.e. the man the heroine will marry).

Perhaps these novels are aimed at a different audience from the readers of the far more explicit Afrikaans women's fiction?

It was noted that the "elephant in the room" in these novels is the whiteness of almost all the characters (and certainly all the protagonists). Despite this, these novels are apparently read in townships and that's also despite the existence of English-language romance novels about Black protagonists. I took a look at the covers of the novels written by the members of the Romance Writers Association of South Africa and they mostly seemed to feature White protagonists too, unlike the romances published by Nollybooks and Kwela Press (which are discussed in this article by the BBC and also this academic one).

Kecia Ali's

Kecia Ali's  Death and the Duchess:

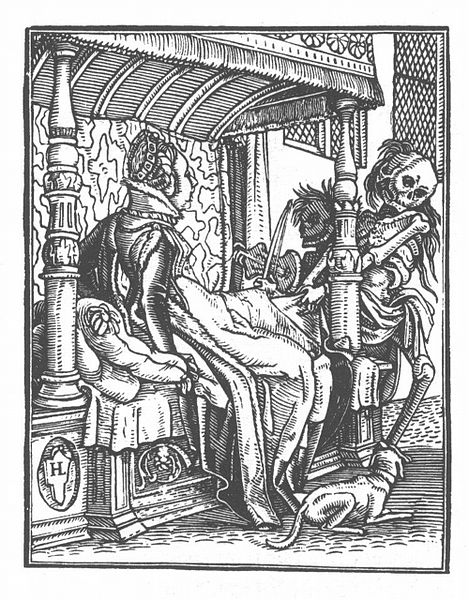

Death and the Duchess:  Three Living and Three Dead: Detail of a miniature of the Three Living and the Three Dead, from the De Lisle Psalter, England (East Anglia), c. 1308 – c. 1340, Arundel MS 83, f. 127v (see

Three Living and Three Dead: Detail of a miniature of the Three Living and the Three Dead, from the De Lisle Psalter, England (East Anglia), c. 1308 – c. 1340, Arundel MS 83, f. 127v (see ![Poena/Poine: Atreus, king of Mycenae, sprawls mortally wounded on his throne. [...] To the right of the throne [...] P](http://www.vivanco.me.uk/sites/vivanco.me.uk/files/images/Poine (Poena).jpg)