Over at Dear Author Janet has been discussing captivity narratives and she states that,

Whether it’s sexual captivity (the forced seduction/rape fantasy), physical captivity (hostage/prisoner/protection), legal captivity (marriage of convenience, especially against the heroine’s will), meta captivity (BDSM play), or some other variation, the process by which one protagonist is often perceived to be held in captivity until she becomes captivated enough to fall in love with the captor-protagonist has become shorthand for drastically intensifying the emotional and physical power imbalances between the romantic protagonists and playing them out in a way that illustrates the tension between captivity and captivation, and the way love theoretically transforms the nature of the relationship to one based on free choice and mutual happiness.

Rape or near-rape of heroines by heroes may be less common in romance than it once was, but "power imbalances between the romantic protagonists" are still extremely common and Robin Harders argues that, "Of all the motifs in genre romance, captivity is one of the most ubiquitous and diverse" (Harders 133).

On the one hand, the popularity of this motif could be read as confirmation of the theory, outlined in Dee Graham's

1994 text Loving to Survive, [in which] Graham identifies Stockholm Syndrome as ‘a universal law of behaviour, which operates when a person existing under conditions of isolation and inescapable violence perceives some kindness on the part of the captor’ [...]. She proposes that at a societal level, women’s love for men emerges from women’s recognition of their subordinate position in patriarchal societies and thus as an effort to bond with the more powerful in society (men) as a means of surviving. [...] Through love, she explains, women not only seek to ‘recoup our losses’ by aligning with those more powerful in society, but ‘hope to persuade men to stop their violence against us’. (Quek 80)

On the other, Harders suggests that "the use of the captivity motif in concert with the happily ever after can provide a challenge to the domestication of love and desire" (146). According to Esther Perel, domestication tends to come into conflict with desire:

at the heart of sustaining desire in a committed relationship, I think is the reconciliation of two fundamental human needs. On the one hand, our need for security, for predictability, for safety, for dependability, for reliability, for permanence -- all these anchoring, grounding experiences of our lives that we call home. But we also have an equally strong need -- men and women -- for adventure, for novelty, for mystery, for risk, for danger, for the unknown, for the unexpected, surprise -- you get the gist -- for journey, for travel [...]. Now, in this paradox between love and desire, what seems to be so puzzling is that the very ingredients that nurture love -- mutuality, reciprocity, protection, worry, responsibility for the other -- are sometimes the very ingredients that stifle desire. Because desire comes with a host of feelings that are not always such favorites of love: jealousy, possessiveness, aggression, power, dominance, naughtiness, mischief. Basically most of us will get turned on at night by the very same things that we will demonstrate against during the day. You know, the erotic mind is not very politically correct.

A vicarious experience of risk and danger may be provided by romance novels. In Joan Wolf's Affair of the Heart, for example, the hero becomes intensely jealous and the heroine finds herself feeling

sheer, primitive terror. [...] The wildness of her resistance had released all of his civilized brakes, and rape was looking at her out of those midnight-dark eyes. [...] She stared up at him, and slow tears formed in her dilated eyes and began to slip silently down her cheeks. She was trembling violently.

Though the haze of anger and lust that possessed him, Jay saw the tears. His hand stilled on his belt buckle [...]. For a brief moment he struggled to hold on to his anger. He wanted to hurt her, to force her to submit to him, to thrust his strength and his maleness on her whether she desired it or not. But the tears were too strong. (171-72)

The heroine does forgive this near-rape and continues to love him. When asked to explain why, she responds: "I'm a masochist, I suppose" (178). She may not mean this literally, but she evidently believes that true love contains an element of risk and danger. She asks the rhetorical question:

What kind of loving was worth anything if it was willing to share? The possessive ones were the passionate ones, the ones who could give completely, utterly, one thousand percent. Perhaps they weren’t always polite, always civilized. But they made the world around them flame with an intensity of feeling and living. (146-47)

She may yearn for this "intensity of feeling" and Perel may believe that humans have a "fundamental need" for danger, but I would question whether all humans have this "need." And if we do, do we need to find it in romantic relationships? There are, after all, some readers who prefer reading about "beta" heroes who would never dream of abducting anyone. Do the romances which feature them propose a different model of romantic love from those which are based around the "power imbalances between the romantic protagonists"?

-----

Harders, Robin. "Borderlands of Desire: Captivity, Romance, and the Revolutionary Power of Love." New Approaches to Popular Romance Fiction: Critical Essays. Ed. Sarah S. G. Frantz and Eric Murphy Selinger. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012. 133-152.

Janet. "Gimme Shelter." Dear Author. 5 March 2013.

Perel, Esther. "The Secret to Desire in a Long-Term Relationship." TED. Feb. 2013.

Quek, Kaye. "Theorising Love in Forced/Arranged Marriages: A Case of Stockholm Syndrome." GEXcel Work in Progress Report Volume VIII: Proceedings from GEXcel Theme 10: Love in Our Time – A Question for Feminism Spring 2010. Ed. Sofia Strid and Anna G. Jónasdóttir. GEXcel, 2010. 75-84. [Whole issue available for download here.]

Wolf, Joan. Affair of the Heart. New York: Rapture Romance, 1984.

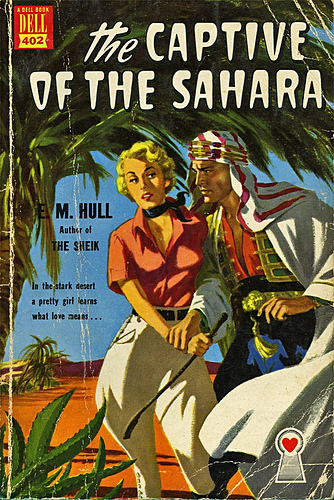

The photo, which I found at Flickr, was taken by Oliver Hammond (Olivander) and was made available for use under a Creative Commons license.

Interesting post, Laura! I

Interesting post, Laura! I remember encountering the idea of possessiveness / jealousy as a marker of love back when I was an adolescent boy, and being utterly mystified by it;I encounter it now in some romance novels--either in extended passages, like the one you quote, or simply as a little grace-note, here and there--and it continues to puzzle me. I recognize it, and I can follow the logic of the heroine's discussion, but I don't feel it. It makes no emotional sense to me, I suppose.

It strikes me that Patel is universalizing a particular cultural construction of love, or of the relationship between love and desire, that probably is neither universal for individuals within any given culture ("your milage may vary," as they say), nor within Western culture across time, nor across cultural boundaries. And she herself conflates a number of very different things in the passage you quote, speaking at one point of "adventure, novelty, surprise" and at another of "jealousy, possessiveness, aggression," etc., as though these two were naturally or comfortably connected with one another.

At some level of abstraction, I suppose that abduction, travel, and a lovely dinner at a new restaurant could all be seen as ritualized markers of having left behind "ordinary time" (almost in the religious sense of the phrase) and entering a liminal world: one marked by a shift away from our ordinary public selves / identities, a hightened emotional state, a greater freshenss and intensity of experience, and so on. (Eva Illouz talks about liminality and love in a number of places; I think Robin Harders mentions it in her essay as well.)

But honestly, that's a very high level of abstraction: an intriguing place to visit, but I wouldn't want to live there. :)