Women's Work: Gender, Respect and Cultural Capital

Analysis of reviews of books by women confirms that women authors, and genres associated with women, continue to receive less prestigious coverage in the media. Lori St-Martin

analyzed the book/arts sections of six newspapers of record in three languages and five countries: Le monde des livres (Paris, France), The New York Times Book Review (New York, USA), Le Devoir (Montréal, Canada), The Globe & Mail (Toronto, Canada), Babelia, in El País (Madrid, Spain, and Ñ, in Clarín (Buenos Aires, Argentina). The data covers a 12-week period, from the week of August 20, 2015 to the week of November 8, 2015. (35)

Some of these publications came close to giving equal coverage to women authors:

The English-language papers were the closest to parity, with 41.2% of books by women for The New York Times and 43% for The Globe & Mail. The Spanish-language papers had by far the lowest figures: 21% for Clarín and 24% for El País, with Le Monde (28.6%) and Le Devoir (34%) falling in between. (36)

However, the picture worsens when one considers the nature of these reviews:

Every newspaper has its own way of granting cultural prestige. Certain writers are marked as more important, usually by giving them prime space or extra space [...] perhaps the most important measure of all is the length of articles; giving an author a long article or more than one article sends a powerful message about his importance. I use the word "his" advisedly, since 9 out of 10 authors featured in this way (87.5%) were men. (38)

The language used to describe books is also very significant in terms of granting or withholding prestige. For example, St-Martin

looked at all the brief headers that introduced the in-depth articles in [French literary magazine] Lire. [...] The only positive words used to describe women's books in headers in the entire issue were the following: "fast-paced", "enjoyable", "whimsically multiplies characters and situations". Books by men, however, were deemed "masterly", "magnificent", "fascinating" [...], "powerful", "superb", "brilliant", and even "necessary, indispensable, revolutionary". This is a partial list. Just by leafing through this magazine, one gets the message, subliminally, that books by women do not deserve high praise, that books that are epic in scope ("an American odyssey", "a masterly ode to life") and touched by greatness are invariably by men. There is no need to proclaim that women's books are none of these things; the entire magazine screams it. It is no coincidence that these attributes - power, mastery, greatness, size and scope - are stereotypically considered to be male, and even phallic. (40)

The unstated criteria by which brilliance, significance and value are assessed all favour particular kinds of authors and works:

what is neglected? Books by or about women and "minorities", including sexual and gender minorities; feminist, lesbian or "radical" books of any kind; "commercial fiction" defined in such a way as to exclude certain categories identified with women (romance novels) while including others deemed more "universal" (crime fiction, thrillers). The big, the major, the important, are concepts still associated with males. (42)

This is, in other words, the literary equivalent of what we see elsewhere in the labour market: even if women are present in larger numbers, the types of work associated with women continue to be considered (often literally) worth less, while types of work linked to traits associated with masculinity are given higher value. The Fawcett Society recently reported that

80% of those working in the low paid care and leisure sector are women, while only 10% of those in the better paid skilled trades are women. [...] Men make up the majority of those in the highest paid and most senior roles – for example, there are just seven female Chief Executives in the FTSE 100.

As

sociologists such as Judy Wajcman (1998) have highlighted [...] the increased entry of women into the labour market has not been associated with feminising or 'softening' the workings of capitalism, even when women workers make it to high-level management positions. For Stephen Whitehead (2002), even though women have been moving more into paid work, the capitalist system retains values that are associated with dominant discourses of masculinity. Masculine values still pervade organisational cultures, locating femininity - and those who are feminine - as 'other' and marginal to much paid work. (Strangleman and Warren 137)

---

Fawcett Society. "Close the Gender Pay Gap." Accessed on 7 September 2017. <https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/close-gender-pay-gap>.

Saint-Martin, Lori. "Counting Women to Make Women Count: From Manspreading to Cultural Parity." Du genre dans la critique d'art/Gender in art criticism. Ed. Marie Buscatto, Mary Leontsini & Delphine Naudier. Paris: E'ditions des archives contemporaines, 2017: 33-46.

Strangleman, Tim and Tracey Warren. Work and Society: Sociological Approaches, Themes and Methods. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2008.

.preview.png)

Emily Grubert and Mark Algee-Hewitt's short article "Villainous or valiant? Depictions of oil and coal in American fiction and nonfiction narratives"

Emily Grubert and Mark Algee-Hewitt's short article "Villainous or valiant? Depictions of oil and coal in American fiction and nonfiction narratives" That may not seem like very many, but there were only 30 works of fiction analysed in total. In the article, specific mention is made of two of them:

That may not seem like very many, but there were only 30 works of fiction analysed in total. In the article, specific mention is made of two of them: The other novel discussed seems to be an inspirational romantic suspense novel and:

The other novel discussed seems to be an inspirational romantic suspense novel and: This Wednesday (21 June) I'll be giving a video presentation to a conference in the Canary Islands. My paper takes Meljean Brook's Riveted as a starting point for taking a look at changing attitudes towards "otherness" in popular romance fiction. I've

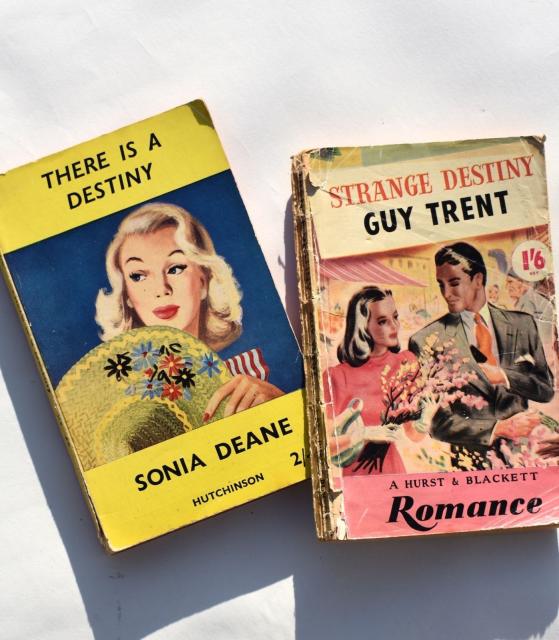

This Wednesday (21 June) I'll be giving a video presentation to a conference in the Canary Islands. My paper takes Meljean Brook's Riveted as a starting point for taking a look at changing attitudes towards "otherness" in popular romance fiction. I've  Hutchison and Hurst & Blackett Paperback Romances

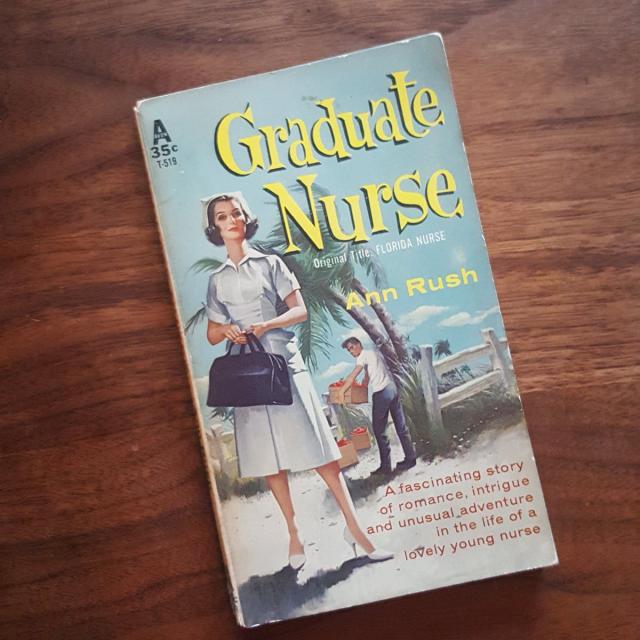

Hutchison and Hurst & Blackett Paperback Romances Graduate Nurse by Ann Rush

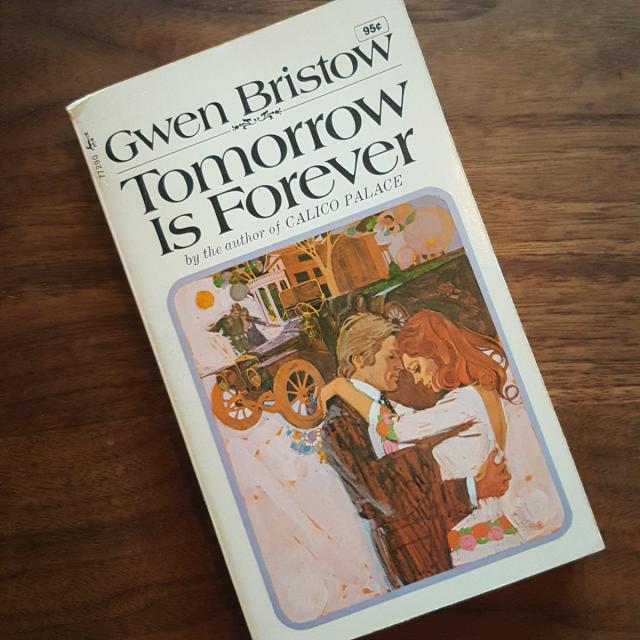

Graduate Nurse by Ann Rush Tomorrow is Forever by Gwen Bristow

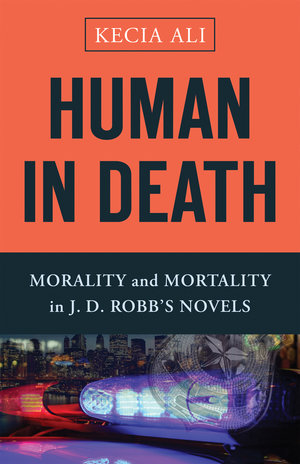

Tomorrow is Forever by Gwen Bristow Kecia Ali's

Kecia Ali's  Death and the Duchess:

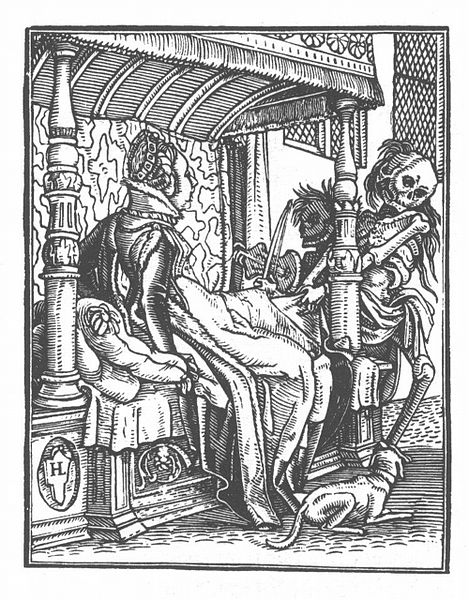

Death and the Duchess:  Three Living and Three Dead: Detail of a miniature of the Three Living and the Three Dead, from the De Lisle Psalter, England (East Anglia), c. 1308 – c. 1340, Arundel MS 83, f. 127v (see

Three Living and Three Dead: Detail of a miniature of the Three Living and the Three Dead, from the De Lisle Psalter, England (East Anglia), c. 1308 – c. 1340, Arundel MS 83, f. 127v (see ![Poena/Poine: Atreus, king of Mycenae, sprawls mortally wounded on his throne. [...] To the right of the throne [...] P](http://www.vivanco.me.uk/sites/vivanco.me.uk/files/images/Poine (Poena).jpg)

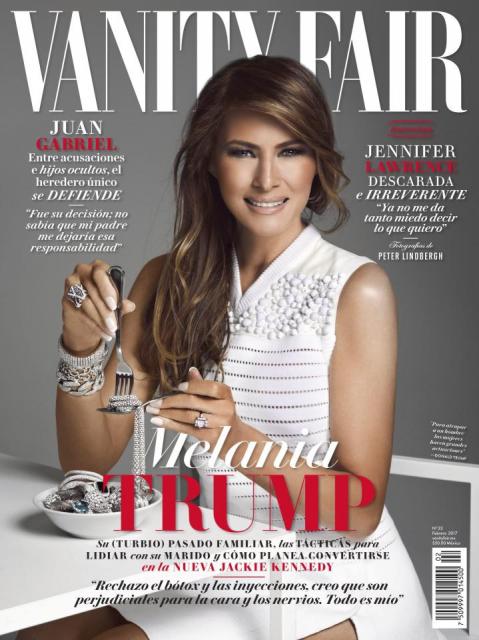

Melania Trump, eating diamonds, on the cover of Vanity Fair (Mexico)

Melania Trump, eating diamonds, on the cover of Vanity Fair (Mexico)