As I mentioned in my previous post, for the final instalment in this series about popular culture's known unknowns and unknown unknowns I'm calling on the expertise of Dr Hannah Priest, who very kindly agreed to write a post for me about female werewolves.

-----

It’s a pleasure to have been asked to contribute to this response to Erin Young’s article on paranormal romance. Like Laura, I begin my response by ‘treading carefully’, as I am aware of ‘known unknowns’ in my own sphere of knowledge (and I’m sure there are ‘unknown unknowns’ too). My current work does not concern contemporary paranormal romance specifically, but rather the wider cultural history of female werewolves. While the novels of Carrie Vaughn and Kelley Armstrong have a significant place in the recent history of female werewolf fiction, I am interested in how they might read in relation to the longer history of presenting she-wolves. Are Kitty and Elena ‘new’ takes on an older tradition? Or are they based on more traditional tropes of presentation? As Laura mentioned at the end of her second post, I am also interested in the ways in which the presentation of the paranormal romance werewolf intersects with lycanthropy in contemporary horror and urban fantasy.

When researching the long cultural history of werewolves, gender is a vital consideration. The question as to why there are more male werewolves than female werewolves has received a number of answers: that lycanthropy is a metaphor for masculine aggression, nobility or psychological bifurcation is the most common response. However, the question itself can be dangerous, as it suggests that a) there is one tradition of werewolves to be explored; b) we can understand or define this tradition by exploring its most common manifestations; and c) manifestations that deviate from the norm are unusual variants that, while interesting, do not alter what the tradition means.

When we actually look at the roughly thousand-year history of female werewolves in literature (and, later, film) – to say nothing of the various European folklores that include werewolves – and compare it to the (admittedly longer) history of male werewolves, I would suggest that it is more productive to consider the female werewolf tradition (which I have termed ‘lycogyny’) as a separate, though intersecting, tradition to that of male werewolves. While these traditions share many tropes, they also draw on different influences and cultural principles. Put simply: when we read a female werewolf, we are accessing a distinct and semi-independent cultural history. Writers of female werewolves do not simply take a male werewolf and give it breasts.

This leads me to this first issue I found when reading Erin Young’s essay on Vaughn and Armstrong’s fictions: in the explorations of their lycanthropy, Kitty and Elena are read against male werewolves, with little reference to other female werewolves. Young states, for instance:

one depiction of the werewolf is notably absent from contemporary paranormal romance: the half-wolf, half-human construction that is recognizable in film examples like Lon Chaney Jr.’s performance in George Waggener’s The Wolf Man (1941), or Michael J. Fox’s comedic portrayal in Rod Daniels’ Teen Wolf (1985). The werewolves of werewolf romance transform completely, from human to wolf, and from wolf to human. They also possess a great deal of control over the transformation. (209)

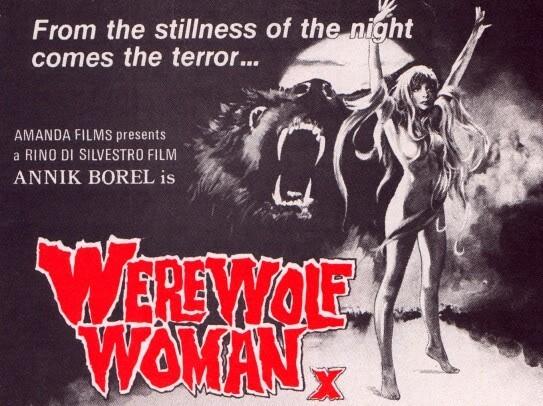

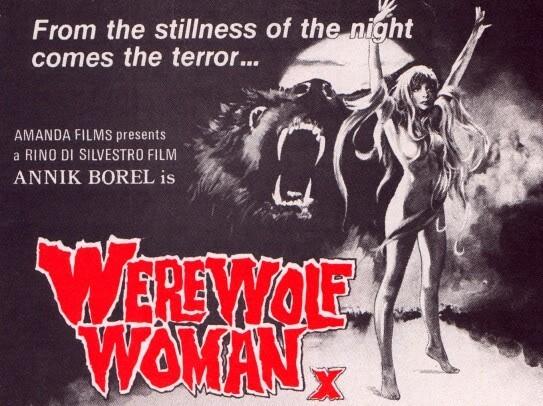

I am not denying that this is true. I would question, though, the relevance of The Wolf Man and Teen Wolf to an examination of Kitty and Elena. These ostensible precedents seem somewhat arbitrary, and specifically male. While the ‘Wolf Man’ paradigm has become a standard cinematic way of representing the male werewolf, this is a late twentieth-century trope. Earlier fictions of male werewolves rarely refer to ‘half-wolf, half-human’ creatures, but almost exclusively rely on complete transformation. This is also true of fictions about female werewolves, and the female of the species has remained stubbornly resistant to the hybrid mode of depiction. Female werewolves are much more likely than males to move from one discrete form to another (the Ginger Snaps trilogy being a notable exception to this).

Young describes Vaughn and Armstrong’s description of werewolf transformation as an ‘alteration’ (209), but, in fact, we might compare it to Victorian narratives about female werewolves (Clemence Housman’s The Were Wolf, for instance), in which transformed women are indistinguishable from natural wolves. Similarly, when Young argues that ‘the transformation does not involve a loss of memory’ (209), we might remember that very few werewolf narratives have actually used the memory-loss trope – it has been used in twentieth-century cinema, but is not by any means the only presentation of lycanthropy (male or female) through the ages.

The paradigm that Young suggests is subverted by these novels, and their construction of ‘no undesirable bodies, no helpless lack of control, no tragic loss of memory or fear of the atrocities one may have committed in werewolf form’ (209), is well-represented by films inspired by The Wolf Man, but has never been the dominant mode of presenting female werewolves. It is also not particularly common in other literary genres containing female werewolves: horror, for instance, often erodes the difference between the woman-in-human-form and the woman-in-wolf-form. In fiction, we might look to Thomas Emson’s Maneater or, more strikingly, Tom Fletcher’s The Leaping, in which the only female werewolf has far less of a break in identity than her male peers. These texts bear comparison with Buffy the Vampire Slayer, whose only female werewolf (Veruca) has far less ‘tragic loss of memory’ and ‘fear’ than her male counterpart (Oz), and Trick ‘r Treat, whose lycanthropic transformation is far from ‘undesirable’.

Despite some compelling discussion of Vaughn and Armstrong’s work, Young sadly continues to discuss aspects of Elena and Kitty’s gendered presentation as ‘new’ without reference to traditions of presenting female werewolves. Most striking in this respect is her claim that Elena’s ‘lycanthropy effectively denaturalizes the domestic sphere, along with its gendered expectations and values’ (219). This is true in the case of Armstrong’s fiction, though I would question its direct application to Vaughn’s. However, rather than being a ‘new’ development in female werewolf fiction, it is one of the most common and abiding tropes of lycogyny. While earlier representations of male werewolves often work to reinforce masculine, hegemonic ideals – I’m thinking particularly of medieval romance narratives like Marie de France’s Bisclavret and the anonymous Guillaume de Palerne – female werewolves (or their medieval counterparts, the wives and stepmothers in werewolf narratives) have consistently denaturalized and subverted the domestic sphere (or other spheres with ‘gendered expectations and values’). We might look to the presentation of Grendel’s mother in Beowulf (a creature associated with wolves, if not a werewolf) as an early example of this. With her perversion of patrilineal society (her son’s heritage is matrilineal, with descent from Cain’s daughters), aggression towards the meadhall and its inhabitants, and alternative ‘family home’ in the mere, Grendel’s mother stands in sharp and violent opposition to the ‘gendered expectations and values’ of the domus.

However, we don’t need to go this far back: Shakira’s 2009 hit ‘She-Wolf’ told us:

A domesticated girl, that’s all you ask of me

Darling, it is no joke. This is lycanthropy.

For Shakira as for the anonymous poet of Beowulf, and numerous other writers in between, lycogyny necessarily requires a rejection and denaturalization of the domestic sphere. In truth, Elena and Kitty are much less forceful in this than other female werewolves – they do not, for instance, kill/kidnap their own children, like the wife of Rosamund Marriott Watson’s ‘A Ballad of the Werewolf’ – which might raise the question of what exactly the ‘alteration’ here is. For me, paranormal romance’s true subversion of lycogyny lies in the nostalgic yearning for the pre-lycanthropic domestic – it may be denaturalized in the narratives, but this often runs contrary to the heroine’s desires.

There is much that I agree with in Young’s article, and (as Laura stated in her post) this response is not a know-it-all corrective. Rather, I also want to draw attention to a common issue with studies of contemporary paranormal fictions: which precedents should be cited. In the case of werewolves (and, perhaps even more, vampires), the temptation is to hold up twentieth-century cinematic monsters as the tradition and to read twenty-first-century romance iterations as a subversion. Sadly, more often than not, it is also twentieth-century cinematic male monsters that are held up as the norm, denying a long and complex history of presenting female monsters. If we follow this approach, we will undoubtedly read paranormal romance’s creatures of the night as subversive and paradigm-altering. However, this is a misleading simplification that ignores millennia of literature and story-telling.

I'm probably going to be moving house soon, which means I'll have to part with quite a few of my books. I'm treating this as an opportunity to take a break from my current project and concentrate on books I've been meaning to read for a while; one of them is Amanda Vickery's The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England (there's a detailed review

I'm probably going to be moving house soon, which means I'll have to part with quite a few of my books. I'm treating this as an opportunity to take a break from my current project and concentrate on books I've been meaning to read for a while; one of them is Amanda Vickery's The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England (there's a detailed review  ia Cheyne's "research focuses on representations of disability and illness in fiction, especially popular genres such as science fiction, romance, horror and crime" and

ia Cheyne's "research focuses on representations of disability and illness in fiction, especially popular genres such as science fiction, romance, horror and crime" and  In Zorzi's case, the barriers relate primarily to his size but Anthony is restricted by his low social class and Amoret by her gender. Indeed, in the first book in the series Amoret is only able to participate in the adventure as a result of dressing as a boy. Thinking about these differing barriers in the light of the social model of disability reminded me of Aristotle's ideas about women:

In Zorzi's case, the barriers relate primarily to his size but Anthony is restricted by his low social class and Amoret by her gender. Indeed, in the first book in the series Amoret is only able to participate in the adventure as a result of dressing as a boy. Thinking about these differing barriers in the light of the social model of disability reminded me of Aristotle's ideas about women: I don't think you need to be Freud to work out the symbolism of that warm pistol but if it still wasn't clear, there's a rather obvious clue in Boone's statement that "I never hired out my gun to the highest bidder. That to a man is like whorin' to a woman - the end of the line" (218).

I don't think you need to be Freud to work out the symbolism of that warm pistol but if it still wasn't clear, there's a rather obvious clue in Boone's statement that "I never hired out my gun to the highest bidder. That to a man is like whorin' to a woman - the end of the line" (218). In "Gender Role Models in Fictional Novels for Emerging Adult Lesbians" Cook, Rostosky and Riggle state that

In "Gender Role Models in Fictional Novels for Emerging Adult Lesbians" Cook, Rostosky and Riggle state that However, not all stereotypes of women's sexuality cast us in a passive role and "a gender bias in the use of language may depend upon which particular sexual conflict is being studied" (315).

However, not all stereotypes of women's sexuality cast us in a passive role and "a gender bias in the use of language may depend upon which particular sexual conflict is being studied" (315).