As Heather Schell has noted,

Evolutionary psychology has popularized the notion that men’s everyday behavior can be better understood by comparison to the habits of large mammals—most especially the more aggressive of the primates—living in patriarchal, aggressive societies. [...] Our cultural fictions have embraced this narrative wholeheartedly but changed the comparison to more charismatic megafauna: dogs and wolves. (109-110)

Popular romance fiction has certainly "embraced this narrative wholeheartedly": the terms "alpha male" or "alpha" are frequently used to refer to the "tough, hard-edged, tormented heroes that are at the heart of the vast majority of bestselling romance novels" (Krentz 107). The term

“Alpha” was originally used in early twentieth-century studies of animal behavior to refer to the dominant individuals in rigidly hierarchical animal societies, such as some types of insects and, in later work, large mammals like primates and wolves. (Schell 113).

One should, however, tread extremely cautiously when comparing animals and humans, not least because "There is a long-standing debate within the field of sexual selection regarding the potential projection of stereotypical sex roles onto animals by researchers" (Dougherty et al 313). According to Dougherty et al,

The subjectivity provided by anthropomorphism (endowing nonhuman animals with human-like attributes), zoomorphism (the converse, endowing humans with nonhuman animal-like attributes), and the sociocultural surroundings researchers finds themselves in, can bias what research is done, how it is done and how the resulting data are interpreted. [...] Perhaps the clearest case in point concerns the study and interpretation of sexual behaviour in nonhuman animals. (313)

For example,

Karlsson Green & Madjidian (2011) showed in their survey of the most cited papers on sexual conflict that male traits were more likely to be described using ‘active’ words, whereas female traits were more likely to be described with ‘reactive’ words, that is, in terms of female traits being a response to male behaviours or male-imposed costs. They ascribed this difference (at least in part) to the anthropomorphic imposition of conventional sex roles on animals by researchers (caricatured as males active, females passive). (314)

However, not all stereotypes of women's sexuality cast us in a passive role and "a gender bias in the use of language may depend upon which particular sexual conflict is being studied" (315).

However, not all stereotypes of women's sexuality cast us in a passive role and "a gender bias in the use of language may depend upon which particular sexual conflict is being studied" (315).

Dougherty et al studied the language used in scientific papers describing

pre- and postcopulatory cannibalism. In terms of the taxonomic coverage, 23 of the species were spiders (35 papers and two reviews), six were mantids (six papers) and one was an orthopteran (one paper, concerning the sagebrush cricket, Cyphoderris strepitans). (314)

They found that,

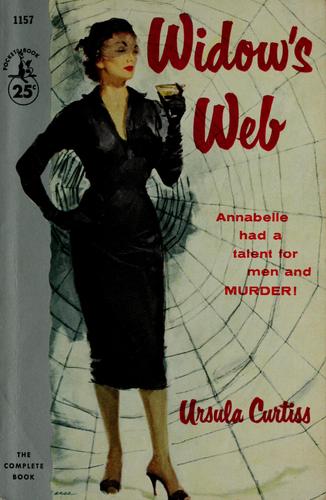

In terms of the words used to describe females, while sexual cannibalism is predicated on the fact that one of the pair ends up being the meal of the other, some of the words used to describe female behaviour are a long way short of being value free: for instance, females have been called ‘voracious’ or ‘rapacious’ more than once. Moreover, if we are concerned with either the causes or consequences of negative sexual stereotyping more generally, the use of such words suggests that there may be scant comfort in our findings here of the assignment of active agency to female animals in the context of sexual cannibalism. Not least this is because it is well-known across human culture that sexually aggressive or violent females are themselves a negative stereotype: from the Gorgons of Greek myth to the femme fatale, the ‘black widow’ or the ‘lethal seductress’ of today. (316)

Given that scientists describing animal behaviour can be influenced by stereotypes derived from human culture, interpreting human behaviour in the light of potentially-anthropomorphised accounts of animal behaviour is problematic. As Dougherty et al conclude,

scientists may bring preconceptions and oversimplifications from their sociocultural surroundings, with ‘general principles’ merely serving to validate those preconceptions. This will forever be an inescapable part of science, and something that we must always be aware of and try and guard against as much as we can. However, there is also the concern that scientific findings about sexual behaviour (or indeed anything else) may travel the other way and provide the basis for sociocultural norms that are chauvinistic, demeaning, or that justify oppression and violence towards some members of society (for instance women or in terms of sexual identity [...]). [...] We suggest that the key message that we should put across is that there are no easy lessons about how we should live or love to be learned from nonhuman animals. (318)

Two of the three papers cited in this post are available online. See below for details.

----

Dougherty, Liam R., Emily R. Burdfield-Steel and David M. Shuker. "Sexual Stereotypes: The Case of Sexual Cannibalism." Animal Behaviour 85.2 (2013): 313-322.

Krentz, Jayne Ann. "Trying to Tame the Romance: Critics and Correctness." Dangerous Men and Adventurous Women: Romance Writers on the Appeal of the Romance. Ed. Jayne Ann Krentz. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1992. 107-114.

Schell, Heather. "The Big Bad Wolf: Masculinity and Genetics in Popular Culture." Literature and Medicine 26.1 (2007): 109-125.