So far West, I end up in the East

I've been finding out a bit more about Westerns, which are one of the (known unknown) dragons at the edge of my popular culture map and while reading the following description of them by Jane Tompkins I was struck by how many parallels there are with popular romance:

I've been finding out a bit more about Westerns, which are one of the (known unknown) dragons at the edge of my popular culture map and while reading the following description of them by Jane Tompkins I was struck by how many parallels there are with popular romance:

The ritualization of the moment of death that climaxes most Western novels and films hovers over the whole story and gives its typical scenes a faintly sacramental aura. (24-25)

This naturally sent me off to re-read what Pamela Regis has to say about moments of ritual death in romances:

The point of ritual death marks the moment in the narrative when the union between heroine and hero, the hoped-for resolution, seems absolutely impossible [...]. Often enough death itself, or an event equated with death, threatens or actually transpires at this point when the barrier seems insurmountable. The death is, however, ritual. The heroine does not die. She is freed from its presence. (35)

Tompkins's mention of a "faintly sacramental aura" also reminded me of Angela Toscano's comments about cliché in the popular romance, which she believes is, in a sense,

liturgical. It is a type of magical speech, as in the language of the Christian mass which transforms the substance of the wafer into the body of Jesus Christ. In the mass this is not metaphor but an actual substantive and physical change. In the world of the narrative, the cliché comprises a series of speeches that, like the mass, become the means by which a substantive transformation occurs in the persons and the bodies of the hero and heroine. The reiteration, the repetition, is the ritualization of the performative utterance. The repetition is what gives the utterance is transformative power.

As Toscano mentions, Lisa Fletcher has focused particularly on the phrase "I love you" so perhaps the speaking of this phrase, rather than the moment of ritual death, are the equivalent of the "ritualization of the moment of death" in the Western? Perhaps the parallels are rather nebulous but Tompkins does later describe "the apocalyptic moment of his shoot-out" as "the sacrament the Western substitutes for matrimony" so perhaps when the Western hero lets his gun do the speaking in a moment of ritualised death, this is the equivalent of a merged "moment of ritual death" and "declaration" ("The scene in which the hero declares his love for the heroine, and the heroine her love for the hero" (Regis 34)) in a romance novel.

Or maybe I'm wandering off at a tangent, with verbal echoes acting as my guides down a slippery slope which will lead to metaphorical destruction. Back to Tompkins on the Western:

The narrative’s stylization is a way of controlling its violence. It is because the Western depicts life lived at the edge of death that the plot, the characters, the setting, the language, the gestures, and even the incidental episodes – a bath, a shave, a game of cards – are so predictable. The repetitive character of the elements produces the same impression of novelty within a rigid structure of sameness as the thousand ways a sonneteer finds to describe his mistress’s eyes. Within a terribly strict set of thematic and formal codes, the same maneuvers are performed over and over. Thus, the question of how a particular action will take place is just as important as what will happen. Half the pleasure of Westerns comes from this sense of familiarity, spliced with danger [...] seeing the same characters do the same thing in a different way each time [...] deepens the experience. You feel you have a stake in how the event will unfold because you know the territory. Part of what the scene is about is its difference from earlier versions; every change in atmosphere, staging, timing, and emphasis producing a different meaning. The imminence of death in the story line and the setting generates these repetitions and makes them titillating. (25)

This appreciation of the subtle novelties which can exist within a rigid structure, and of the pleasures to be derived from "familiarity, spliced with danger" strikes a chord with me as a reader of romance novels. No doubt this is because both are "genre fiction." And the similarities between romances and sonnets have also been noted, by Jennifer Crusie.

As a follow-up to the mention of titillation, though, I let the verbal echoes carry me away again while reading Tompkins's description of the opening scene of Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage:

The heroine, Jane Withersteen, a young Mormon woman who owns a large ranch the Mormon power structure covets, is about to watch her best rider, Bern Venters, be whipped by the Mormon elders because he is a Gentile. [...] Afraid that Bern would kill one of the Mormon elders she looks up to, Jane Withersteen has symbolically emasculated him by taking his guns away. But after Lassiter saves him, Venters asks for them back in an exchange that advertises the phallic nature of the regime Lassiter represents:

Talk to me no more of mercy or religion – after to-day. To-day this strange coming of Lassiter left me still a man, and now I’ll die a man. ... Give me my guns. (17)

[...] But even though the gun is obviously a symbol for the penis, manhood, in this scenario, does not express itself sexually. Violence is what breaks out when men get guns. (32-33)

So, we've got phallic violence and death in a type of popular fiction strongly associated with men; sex and the "little death" in popular fiction strongly associated with women. Given the existence of Western romances, though, I didn't think it could really be a case of "East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet" so I wasn't entirely surprised when I happened to come across the following in a review of Louis L'Amour's Radigan (1958):

It [...] would have been nice for the falling in love bit to be left out as this seems to be a bit of a redundant theme in westerns, leaving it out would have set it apart from other westerns, but [...] I won’t hold it against Louis L’Amour.

Seems Louis lived up to his name. And to change genre but not location or topic, here are some lines from Rawhide:

Through rain and wind and weather,

Hell bent for leather,

Wishin' my gal was by my side.

All the things I'm missin',

Good vittles, love, and kissin',

Are waiting at the end of my ride. [...]My heart's calculatin',

My true love will be waitin':

Waitin' at the end of my ride.

------

Peters, Tony. "Book Review - Louis L'Amour - Radigan." 3 January 2010.

Regis, Pamela. A Natural History of the Romance Novel. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2003.

Tompkins, Jane. West of Everything: The Inner Lives of Westerns. New York: Oxford UP, 1992.

Toscano, Angela. "The Liturgy of Cliche." 27 Nov. 2011.

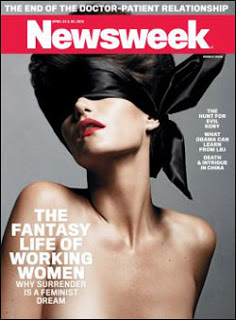

To desire is necessarily to exist in a state of fantasy: it is to entertain the possibility of obtaining something one does not have - power, love, adventure. Given that all desire is fantastical by its very nature, it might seem odd that some projections of desire are criticized because they seem inauthentic. Popular romance fiction, for instance, has long been derided as the worst kind of fantasy. There is the sense that publishers such as Silhouette, Harlequin and Mills & Boon provide emotional and erotic titillation for women who are too weak to achieve fulfilment in 'real life'. Only such fools, with no genuine hold on reality, could lend credence to the impossibly beautiful, monolithic, creatures to be found in these novels. There is the suggestion that these works are not so much fantasy as false consciousness. The passion is at once euphemized and overstated; this is pornography for those who cannot bear to own up to sexual appetite. Alternatively, such caricatures of desire may provide an excessive compensation in the sphere of the erotic for a variety of other wants: the imaginary lover can requite not merely sexual loneliness, but also a poorly paid job, or a general feeling of insignificance.

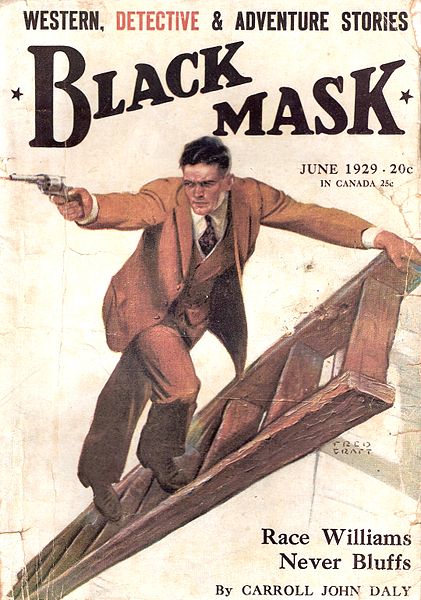

To desire is necessarily to exist in a state of fantasy: it is to entertain the possibility of obtaining something one does not have - power, love, adventure. Given that all desire is fantastical by its very nature, it might seem odd that some projections of desire are criticized because they seem inauthentic. Popular romance fiction, for instance, has long been derided as the worst kind of fantasy. There is the sense that publishers such as Silhouette, Harlequin and Mills & Boon provide emotional and erotic titillation for women who are too weak to achieve fulfilment in 'real life'. Only such fools, with no genuine hold on reality, could lend credence to the impossibly beautiful, monolithic, creatures to be found in these novels. There is the suggestion that these works are not so much fantasy as false consciousness. The passion is at once euphemized and overstated; this is pornography for those who cannot bear to own up to sexual appetite. Alternatively, such caricatures of desire may provide an excessive compensation in the sphere of the erotic for a variety of other wants: the imaginary lover can requite not merely sexual loneliness, but also a poorly paid job, or a general feeling of insignificance.  Of course such criticism could also be offered of the characters and scenarios of male-oriented popular fiction, who are usually every bit as predictable and fantastic: the spy who is equally adept at unlocking women's desires and unravelling the plans of evil empires; the silent, unbreakable Western hero; the detective who outwits and outpunches low-life villains. The hard-boiled quality of masculine fictions suggests a claiming of the real, even though we as real readers in the real world may detect the wishfulness of it all. (Stoneley 223)

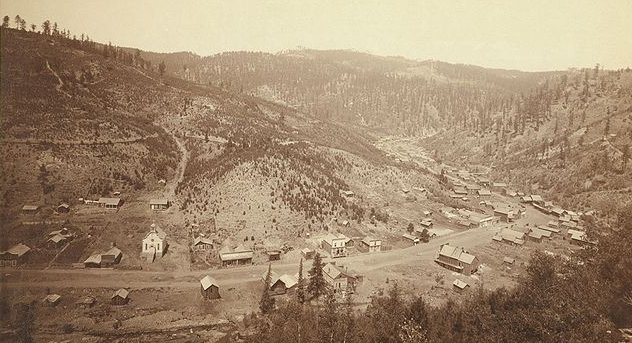

Of course such criticism could also be offered of the characters and scenarios of male-oriented popular fiction, who are usually every bit as predictable and fantastic: the spy who is equally adept at unlocking women's desires and unravelling the plans of evil empires; the silent, unbreakable Western hero; the detective who outwits and outpunches low-life villains. The hard-boiled quality of masculine fictions suggests a claiming of the real, even though we as real readers in the real world may detect the wishfulness of it all. (Stoneley 223) Galena, S. Dakota, 1890

Galena, S. Dakota, 1890

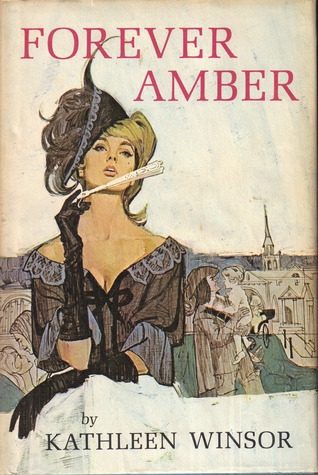

revealed its age's secret desires and myths. The headstrong Amber - beautiful, empowered, resilient - represents a rebellion other women identified with, even, like my mother, as they hid the book away in the cupboard.

revealed its age's secret desires and myths. The headstrong Amber - beautiful, empowered, resilient - represents a rebellion other women identified with, even, like my mother, as they hid the book away in the cupboard. In the context of the study of popular culture, "reports that say something hasn't happened [before] are always interesting to me." One relatively recent example,

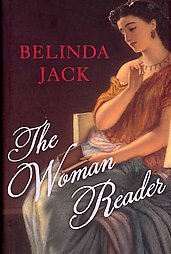

In the context of the study of popular culture, "reports that say something hasn't happened [before] are always interesting to me." One relatively recent example,  As you may have deduced from my recent posts, I've been slowly working my way through Belinda Jack's The Woman Reader, which

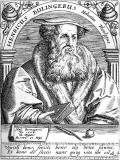

As you may have deduced from my recent posts, I've been slowly working my way through Belinda Jack's The Woman Reader, which Heinrich Bullinger, the Swiss reformer, was author of The Christen state of matrimony, moost necessary and profitable for all of them, that intend to live quietly and godlye in the Christen state of holy wedlocke newly set forth in Englyshe (1541), translated by Miles Coverdale. It was enormously popular and went into eight editions. Although one of the first rules states the almost universally recognised necessity that 'The husband is the heade of the Wyfe', Coverdale's translation also stresses the need for husband and wife to be friends, as well as lovers, and the rewards of caring for each other particularly at the outset of marriage.

Heinrich Bullinger, the Swiss reformer, was author of The Christen state of matrimony, moost necessary and profitable for all of them, that intend to live quietly and godlye in the Christen state of holy wedlocke newly set forth in Englyshe (1541), translated by Miles Coverdale. It was enormously popular and went into eight editions. Although one of the first rules states the almost universally recognised necessity that 'The husband is the heade of the Wyfe', Coverdale's translation also stresses the need for husband and wife to be friends, as well as lovers, and the rewards of caring for each other particularly at the outset of marriage. In

In