White-Washing South Africa

In "The Empire of Romance: Love in a Postcolonial Climate" (in End of Empire and the English novel since 1945) Deborah Philips writes that,

For Mills & Boon writers and readers of the 1950s, South Africa was not the country of apartheid, but rather [...] 'the colourful, romantic background of South Africa'. South Africa may have been presented as exotically 'colourful' to British readers of Mills & Boon, yet the writers were notably reticent on the subject of colour. Mills & Boon had a large market in South Africa, and the editors were careful of white South African sensibilities. A mixed race romance could not be countenanced in novels set in South Africa nor, indeed, anywhere else in the Mills & Boon world. [...] The heroes and heroines of these novels were uncompromisingly white, as was their social world. Alan Paton's excoriating account of life in South Africa, Cry the Beloved Country, which had been published in 1948 (and filmed in 1951), made the iniquities of apartheid starkly apparent to a wide readership. Even so, the political context of contemporary South Africa was firmly positioned beyond the boundaries of what the romantic novel in the postwar world could discuss. (Philips 118)

That this was a deliberate decision on the part of Mills & Boon is made clear by the fact that "One Mills & Boon author, Alex Stuart, was taken to task for writing a sympathetic anti-apartheid character" (Philips 120). The episode is described in some detail by Joseph McAleer:

That this was a deliberate decision on the part of Mills & Boon is made clear by the fact that "One Mills & Boon author, Alex Stuart, was taken to task for writing a sympathetic anti-apartheid character" (Philips 120). The episode is described in some detail by Joseph McAleer:

In 1964 [Alan] Boon asked Alex Stuart for major changes to her latest manuscript, entitled The Scottish Soldier. In her submission letter, Stuart realized that there might be problems with this novel. 'Please understand that I want Mills & Boon to publish this one very much but I know your reputation for publishing "pleasant books" is of great value to you and, of course, wouldn't want to damage this,' she told Boon. The problem concerned Stuart's insistence that the heroine's father act as a crusader in race relations in Lehar, a fictional African nation. He publishes a book demanding equal rights for black people, and targets South Africa and its apartheid laws. This was hardly the stuff of a Mills & Boon novel, Stuart admitted, and at first she did offer a change in background:

[...] I could (with difficulty) make the father an American who got involved in the Colour Question in one of the Southern States - do we care about American sales? Personally, I think that having the book banned in S. Africa because it was anti-apartheid ought to increase its sales elsewhere but this is your province, not mine. ... This is the sort of 'romantic' novel I am now hoping to be able to write (Occasionally, not all the time) as I believe it to be the kind which must come in the future, if the romantic novel is to hold its new, young readers and go forward, rather than backward. (169)

In the end Stuart was unwilling to make the major changes Boon required and "decided to speed up work on her next Mills & Boon novel" which she described as "a safe Mills & Boon straight-jacketed [sic] novel" (McAleer 270).

Kathryn Blair's The House at Tegwani (1950) was one of the books set in Africa which was approved by Boon. Deborah Philips notes that in it "The few black characters whom Sandra [the heroine] does encounter are all servants, and these are, without exception, described as 'cheerful' and loyal to their white employers" (119) and

The 'abodes' of the black South Africans themseves, their 'native dwellings', are kept remote and at a safe distance from Sandra and from the small white settler town of Pietsburg. This geographical distance would conform to the segregated racial areas which had become ever more rigid after the 1948 election, although these developments are never mentioned. The 'native shacks' instead become picturesque elements in an exoticised and distant South African landscape:

Shrub-crusted veld, with here and there a few cattle gathered at a waterhole or a huddle of native shacks in the midst of which a fire burned and a hanging pot boiled, so that steam merged with the twig smoke and rose into the richly coloured evening sky.

Here, the 'natives' are rendered invisible, their own domestic lives literally turned into smoke. (120)

However, what seems "pleasant" in one era, and to one group of readers, may not seem quite so pleasant at another time or to other groups of readers and so, although

the South Africa of the early 1950s could be presented as reassuringly white [...] by the 1960s it had become a more uneasy setting for a British heroine. [...] Alan Boon [...] described a concern among editors of women's magazines of the period - Mills & Boon novels were often sold as magazine serialisations - that politics might intrude upon the romance:

I find there is a certain nervousness in some serial quarters about using the African background. I think some of the editors may be worried that there might be political trouble just as they are running the serial. In my view, it would not matter if that did occur. (Philips 122)

Of course, one might well retort that apartheid constituted "political trouble" which was already occurring. Boon may have been prepared to overlook that, but presumably the financial power of the magazine editors did have some effect: he advised at least one of his authors "to set her novels somewhere other than South Africa. She cheerfully moved her locations to other African settings, interchangeable in their exoticism and foreignness" (122).

Next week I'll be taking a look at Meljean Brook's Riveted (2012) which one could perhaps describe as a romance of "the kind which must come in the future, if the romantic novel is to hold its new, young readers and go forward, rather than backward."

---

McAleer, Joseph. Passion’s Fortune: The Story of Mills & Boon. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

Philips, Deborah. “The Empire of Romance: Love in a Postcolonial Climate.” End of Empire and the English Novel Since 1945. Ed. Rachael Gilmour and Bill Schwarz. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2011. 114-133.

---

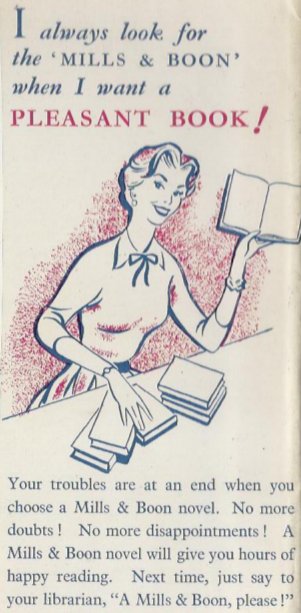

The image of the Mills & Boon reader comes from the inner back cover flap of one of my Mills & Boons. It was published in 1961, and I've included it because it makes it clear what Alex Stuart was alluding to when she referred to "your reputation for publishing 'pleasant books'."