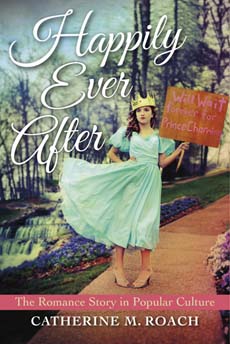

I've been reading Catherine Roach's Happily Ever After: The Romance Story in Popular Culture, in which she proposes that one of "essential elements of the romantic love story" (21) is that

I've been reading Catherine Roach's Happily Ever After: The Romance Story in Popular Culture, in which she proposes that one of "essential elements of the romantic love story" (21) is that

Romance involves risk. Love doesn't always work out. In fact, it may fail spectacularly. The story of romance novels, which are technically romantic comedies in that they end happily, can all too easily turn into the failure of love in romantic tragedies such as the iconic Romeo and Juliet. This knowledge haunts romance stories as a shadow text, often present within the story as the path avoided: The book opens with a bad boyfriend whom the reader knows is on his way out. A previous generation's failed romance is redeemed through the current characters. [...] Readers feel this risk in the main story itself, which in "real life" would be unlikely to work out but which within the fantasy space of the romance always, miraculously, does: The heroine sleeps with the hero while he's still the emotionally closed-off cowboy or the philandering rake, but instead of the obvious scenario wherein he leaves her heartbroken, her act of giving herself to him opens his heart. (24)

I can't argue with the assertion that "Love doesn't always work out". Whether that makes love feel like a big "risk", though, is another matter. I can think of plenty of things I, personally, would think of as being a lot riskier. In romance, however, quite a lot of characters are happy to do things which I'd categorise as higher risk but are nontheless wary of falling in love: presumably they assess love as something which is much more likely to cause them pain.

Roach suggests that love is risky because it

is never a simple joy or pleasure, if for no other reason than the sure and stern knowledge of the beloved's eventual death. In every moment of love is this proleptic experience of loss, making all deeply felt love poignant and tragic. Such is one cost of love. (128)

The alternative, though, is presumably either to only love things which can't die (i.e. durable material objects) or not to love at all (which has its own costs). Presumably the extent of the risk of loving mortal beings varies according to how much one dwells on the "sure and stern knowledge" and how deeply (and perhaps to some extent how exclusively) one loves.

Another factor in the risk assessment is the nature of the lover. As Roach has suggested, romance as a genre is full of examples of people who are a bad risk and if "what love is really about [is...] accepting people for what they are, and forgiving even the worst in them" (Arbor 191) then it's bound to be riskier if the person one's accepting and forgiving is prone to doing hurtful things.

Roach distinguishes between what happens in healthy relationships and what happens when

Roach distinguishes between what happens in healthy relationships and what happens when

Love can and does go dreadfully wrong. Dates turn into rape. Domestic partner abuse batters and kills people [...]. The romance novel rake, in reality, rarely reforms [...]. The cruel truth is, love can break your heart; shred your self-esteem; ruin your finances; leave you with unwanted pregnancy, disease, and social shame; get you killed by a stalker who won't let go. [...] These [...] tragic stories of love [...] are [...] love as the practice of bondage, or, more precisely, what I propose to call love as bad bondage. Such love can entail bondage to an unworthy partner, bondage within cycles of abuse, and bondage to low self-esteem such that one feels undeserving of anything better in one's love life. (127)

In contrast, Roach suggests,

As a true love, I must be willing to act, in an extension of self, in ways that are caring, affectionate, and respectful, in order to nurture my beloved's growth. Such true love also implies that, as I nurture my beloved's growth, I nurture my own as well. We cannot, do not, love another truly if we abandon the duty to love ourselves and to act in our own best interests. True love, in other words, does not make one into a martyr or a doormat. [...] And yet it's not so simple, because true love, or good love, entails its own type of bondage as well. [...] This bondage or binding involves a restriction of freedom that is key to popular culture's vision of romantic love. To love is to forsake all others, to cleave to a one and only, to tie the knot. (127-28)

Or as one romance hero puts it:

'Love is when you can't live without someone - when everything seems dull and empty because they're not there - when you think of them the moment you wake and they're there in your thoughts as you fall asleep - they fill your dreams [...] But true love is more than that [...]. True love isn't selfish or possessive - it values the other person's feelings more than your own. When you told me about Simon I was furious, I hated the way he had behaved - the selfish, obsessive sort of love that had trapped you - blackmailed you emotionally when you couldn't love him back. If you really love someone you want what's best for them - even if that means letting them go, leaving them free to be with someone else. (Walker 275-76)

That's very noble, but it does sound potentially rather painful if the love is one-sided yet still binding.

So can a risk assessment help us avoid love altogether, or might it only assist us in directing our feelings towards a less-risky love-object? Love itself may be inescapable, if the extremely rational hero of Karen Lord's The Best of All Possible Worlds is correct in thinking that love, although

it comes attended by various physical reactions which manifest as emotions, [...] is one of the drives.'

'Oh,' I said. 'Like hunger, or wanting to procreate, or the desire to protect one's offspring.'

'Yes. I have identified you as the most appropriate mate, probably through an unconscious assessment of pheromones, mental capacity and, of course, social compatibility.'

'So you're saying you like how I smell, you like how I think and you like to hang out with me?' I was amused, but genuinely warmed at such a unique declaration of love. [...]

He drew me into his arms and into his mind. He saw how I valued his selflessness and trusted his integrity, even when he exasperated me by being inflexible. I showed him my admiration for his physical strength, intelligence and psionic abilities, and the gentleness that complemented all those qualities. I even allowed him to see that I had found him physically attractive from the moment we first met.

'So,' he said lightly, and I knew he was teasing me because he was somewhat shaken. 'You believe that I possess certain characteristics which you would like to be passed on, via genetic transfer and mentoring, to your children.'

I began to laugh. (Karen Lord, The Best of All Possible Worlds, 311-312)

------

Arbor, Jane. 1970. The Feathered Shaft in The Second Anthology of 3 Harlequin Romances by Jane Arbor. Don Mills, Ontario: Harlequin, 1977. 6-203.

Lord, Karen. The Best of All Possible Worlds. London: Jo Fletcher, 2013.

Roach, Catherine M. Happily Ever After: The Romance Story in Popular Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016.

Walker, Kate. Calypso's Enchantment. Richmond, Surrey: Mills & Boon, 1994.

The heart with the handcuffs came from Flickr and was created by Jason Clapp. It was made "available for download under a Creative Commons license."