Politics and Magazine Romance Stories

In my last post I quoted Porter and Hall's statement that "Work is beginning to appear on the fiction in women's magazines and the sexual messages it conveyed" (267). They refer to "Part Three: Realistic Fantasies: The World of the Story Papers" of Billie Melman's Woman and the Popular Imagination, Joseph McAleer's Popular Reading and Publishing in Britain 1914-1950 and an article by Bridget Fowler. As the latter was the most readily accessible of the three, I promptly went and found myself a copy.

Fowler argues that "1930s popular stories can be seen [...] as legitimating the social order and thus indirectly providing social control" (95) though she cautions that the attitudes expressed in these stories may be only

partially shared by the readership. [...] It is very likely that the practical action of the readers emerges also from other cultural values - such as those of dissent and militancy - which are totally absent from the story universe, while the adherence to some story values may well be more at the level of the ideal or fantasy than concrete reality. (96)

One plot type she discusses which is, I think, rather less common nowadays, requires the

device [...] in which 'cryptoproletarian' characters are used. The heroine, in love with a doctor, may emerge ultimately to be not truly working-class but a foundling in some slum and brought up by working-class parents; a hero may be cut off by his father and family and forced to live a working-class mode of existence or an unexpected inheritance may alter the total dependence of the lower class heroine on the upper class hero. Thus, in social origin the hero and heroine may ultimately turn out to be alike although the bulk of the story has concerned the proving of their fitness to marry each other. It is tempting to align these stories with the earlier fairy story in which once the princess had brought herself to kiss the beast or marry the frog, he became a prince. The analogy makes the class insult even more apparent. (107)

The romances analysed by Kim Gallon were written at roughly the same time, and also appeared in magazines or newspapers but their context, and therefore their politics, are rather different. She recently posted at the Popular Romance Project about the romances to be found

in the pages of early 20th-century black magazines and newspapers. Mostly known for strident protests against racial discrimination, the black press in the 1920s and 1930s also published romance fiction, which offered African Americans an opportunity to escape into worlds filled with the heady ups and heartbreaking downs of romantic love. Scholars of the African American literary tradition and of popular romance have paid virtually no attention to romance found in the black press. On the romance side, the late 20th century has often been characterized as the starting point of black romance stories, with earlier short or serial stories, simply forgotten. [...]

Despite the seeming absence of political and racialized content in “The Dark Knight” and similar stories, black popular romance, as Conseula Francis has argued, is inherently political. Its existence automatically counters the insidious and negative stereotypes of criminality and hypersexuality historically ascribed to African Americans. In “The Dark Knight,” we see Rod and Lyla restrain themselves from engaging in a pre-marital sexual encounter, preserving, through their actions, the sanctity of marital sex and the domestic ideal. Just as significantly, “The Dark Knight” challenged the common idea that African Americans lacked the capacity for romantic love, a love that has been and continues to be integrally linked with a white, bourgeois value system.

William Gleason's article on story papers, published in 2011, does not explore the politics of their romance stories but he too suggests that romances published in magazines deserve further critical attention, not least because in his opinion

The mass marketing of modern romance fiction in North America began not with the emergence of Harlequin Books in the 1950s but during the dime novel and story paper boom of the 1860s and 1870s.

--------

Fowler, Bridget. "'True to Me Always': An Analysis of Women's Magazine Fiction." British Journal of Sociology 30.1 (1979): 91-119.

Gallon, Kim. "Romance in Black Papers." The Popular Romance Project. 10 January 2013.

Gleason, William. "Belles, Beaux, and Paratexts: American Story Papers and the Project of Romance." Journal of Popular Romance Studies 2.1 (2011).

Porter, Roy & Lesley Hall. The Facts of Life: The Creation of Sexual Knowledge in Britain, 1650-1950. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995.

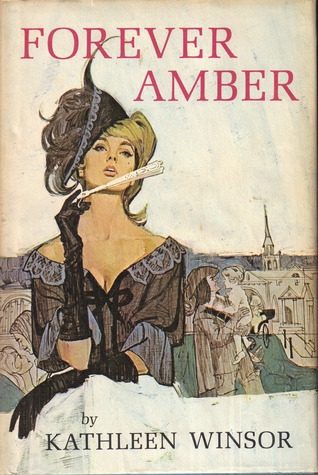

revealed its age's secret desires and myths. The headstrong Amber - beautiful, empowered, resilient - represents a rebellion other women identified with, even, like my mother, as they hid the book away in the cupboard.

revealed its age's secret desires and myths. The headstrong Amber - beautiful, empowered, resilient - represents a rebellion other women identified with, even, like my mother, as they hid the book away in the cupboard. This isn't quite a promise of eternal life with a God who

This isn't quite a promise of eternal life with a God who  I've been reading Anne Cranny-Francis's Feminist Fiction: Feminist Uses of Generic Fiction (1990). In it she defends genre fiction, whose

I've been reading Anne Cranny-Francis's Feminist Fiction: Feminist Uses of Generic Fiction (1990). In it she defends genre fiction, whose