Overthinking things?

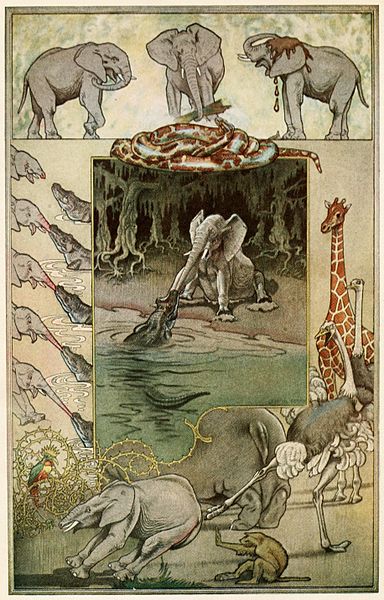

When I was young I was read the story of the Elephant's Child

who was full of ‘satiable curiosity, and that means he asked ever so many questions. [...] He asked questions about everything that he saw, or heard, or felt, or smelt, or touched, and all his uncles and his aunts spanked him. And still he was full of ‘satiable curiosity!

That poor little elephant suffers a lot as a result of his curiosity. He's not just spanked: he gets his nose irrevocably stretched by a crocodile. He learns, though, that the growth is a positive development and the story ultimately condemns the family who do the spanking.

I much prefer this story about curiosity and its rewards to the idea that curiosity kills cats or that bad things emerge when Pandora's Box is opened. So in the past when people have mentioned the possibility that the academic study of popular romance could involve overthinking things, I was just puzzled. Isn't thinking about things always a good thing?

Recently, though, I've seen a couple of things which have got me rethinking the idea of overthinking.

- for every person who is interested in interrogating and contextualizing her own choices in reading material, I feel certain there are more people who just want to read what they want without over-thinking it or being questioned in any way. I guess I am trying in a clumsy roundabout way to figure out if there are ways in which academic or “wonky” incursions into the online romance community are perceived as a negative development and, if so, where, and for whom?

- a college writing instructor, [...] offered a course that asks students to examine everyday arguments: that is, to use rhetorical and critical theory to construct academic essays about the arguments that we daily encounter in the news, in popular culture, and online. (1)

- When I taught this course in the winter of 2011, I encountered a problem. For their third formal essay of the semester, students wrote a critical analysis of a television show of their choice; not surprisingly, most students picked programs that they regularly watched and enjoyed. This was by far students’ favorite assignment, and in fact these essays were the strongest and most sophisticated of the semester. One by one, however, students turned in written drafts that eviscerated the shows they spoke so animatedly and lovingly about in class. The student who had seen every syndicated episode of Friends scrutinized the show’s lack of socioeconomic and racial diversity. The student who routinely watched The Bachelor each week with her friends interrogated its portrayal of romantic love and marriage. And on the day when the final draft was due, Maria – who wrote a beautiful analysis of how the show Entourage perpetuates hegemonic masculinity – asked me, “Does this mean I can’t watch Entourage anymore?” (1-2)

- If Maria’s Entourage essay gave the show a critical viewing, how was she watching it before? Was she viewing it uncritically? If so, how does this characterization of her viewing practices position Maria’s expertise about the show in the classroom? What knowledges, practices, or subjectivities actually comprise Maria’s expertise, and how do they compare to academic ways of thinking? Is there another way to understand Maria’s pleasure from watching Entourage besides saying it is uncritical? What kind of affect is pleasure, and where does it fit in the writing classroom? What happens when texts that students use primarily for purposes of pleasure and entertainment are brought into the classroom for critical analysis? What happens to students in such situations? And finally, how should I respond to Maria’s question? (2)

- romance readers take part in shaping how textual conventions are understood, what texts mean beyond their narrative function, and how they circulate. Moreover, some women use popular romance fiction to maintain intimate connections to friends and family members, reflect on and transform their personal lives, and demonstrate collective and civic engagement online. These experiences may remain invisible in classrooms that focus primarily on the role of popular culture texts in reproducing hegemonic ideologies. (15)

- critical literacy pedagogies can actually disempower students when such pedagogies invite popular culture texts into the writing classroom but position such texts primarily as ideological artifacts that require critical, academic “tools” to excavate their hidden meanings. (13)

- In a post celebrating her blog's first anniversary, Pamela of Badass Romance said that

- They're questions which also preoccupied Stephanie Moody who, as

- Then

- Like Pamela, Stephanie began to ask herself questions about questioning and critiquing:

- What, in other words, if academics are not the curious little elephant but are some of the older animals in the story? I've never really taught any students, which makes it hard for me to see myself in this role, but could we be the pompous yet helpful Bi-Coloured-Python-Rock-Snake who asks the elephant "questions, in the Socratic mode of instruction" (Meyer)? Perhaps we're the Kolokolo bird, with its mournful cry of "‘Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees, and find out," sending the elephant off on a possibly instructive but also dangerous and painful quest? Or are we the crocodile, forcefully pulling the elephant's nose while trying to turn him into fodder for our careers?

Maybe I'm overthinking things and should just sit back and enjoy some pictures instead?

- Pretty, aren't they? But I'm still asking questions. And in case you're wondering, Stephanie Moody concludes that

- and so

- I'm not sure that academics who are also romance readers "position such texts primarily as ideological artifacts" but I can see how we might come across as doing that. In which case, we might seem to be taking an authoritative position which disempowers other romance readers.

On the other hand, the online romance community isn't being forced into a college composition classroom, and those of us who are both academics and romance readers are still romance readers, so should being an academic (or simply being a reader who takes a more academic/"wonky" perspective) disbar someone from taking "part in shaping how textual conventions are understood, what texts mean beyond their narrative function, and how they circulate"?

- --------

- Meyer, Rosalind, 1984. "But is it Art? An Appreciation of Just So Stories." Kipling Journal 58 (232). 10-33. Qtd. in Lewis, Linda. "The Elephant's Child." Kipling Society, 30 July 2005.

Moody, Stephanie Lee, 2013. "Affecting Genre: Women's Participation with Popular Romance Fiction." Ph.D thesis. University of Michigan.

Mate Selection: "Mr Collins meant to choose one of the daughters" (illustration by Hugh Thomson,

Mate Selection: "Mr Collins meant to choose one of the daughters" (illustration by Hugh Thomson,

However, not all stereotypes of women's sexuality cast us in a passive role and "a gender bias in the use of language may depend upon which particular sexual conflict is being studied" (315).

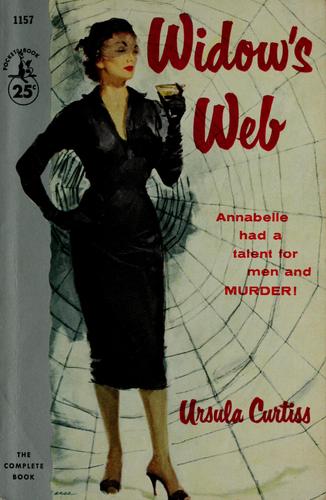

However, not all stereotypes of women's sexuality cast us in a passive role and "a gender bias in the use of language may depend upon which particular sexual conflict is being studied" (315). Unlike Bindel, it turns out that Motte cares extremely deeply about whether "the books are trashy, formulaic or pulp fiction" and, also unlike Bindel, Motte focuses all his attention on just one romance: Sharon Kendrick's The Playboy Sheikh’s Virgin Stable-Girl.

Unlike Bindel, it turns out that Motte cares extremely deeply about whether "the books are trashy, formulaic or pulp fiction" and, also unlike Bindel, Motte focuses all his attention on just one romance: Sharon Kendrick's The Playboy Sheikh’s Virgin Stable-Girl. Norrey Ford's The Love Goddess (1976) is a novel about an academic. Admittedly, Professor Bart Ransom's research is rather more exciting than mine: he's working on an underwater archaeology site in the Aegean and requires absolute secrecy from his collaborators because the wreck promises to be so important it would attract the attention of "Pirates, hijackers! The word gold could bring them running from all quarters of the earth" (42). My research won't produce any gold or priceless ancient artefacts but there's something about Bart's explanation of how he feels about his work that did strike a chord with me:

Norrey Ford's The Love Goddess (1976) is a novel about an academic. Admittedly, Professor Bart Ransom's research is rather more exciting than mine: he's working on an underwater archaeology site in the Aegean and requires absolute secrecy from his collaborators because the wreck promises to be so important it would attract the attention of "Pirates, hijackers! The word gold could bring them running from all quarters of the earth" (42). My research won't produce any gold or priceless ancient artefacts but there's something about Bart's explanation of how he feels about his work that did strike a chord with me:

I was working with primary texts which I can't expect my readers to know well (or, in most cases, at all) so perhaps that meant I was more inclined to use longer quotations, which provide a bit more context and also give readers more of a taste of the individual authors' "voices." As far as quotations from academic secondary texts are concerned, I was hoping that the book would appeal to interested general readers as well as to romance scholars, so again perhaps that meant I included slightly longer quotes than would have been necessary if I'd only been writing for a scholarly audience. Having said all that, though, it hadn't even occurred to me that any of my quotes were too long. I think that a "reliance on long block quotes" may form part of my usual writing style. I'll bear this criticism in mind for the future but I can't promise to change; I suspect that what seems "too long" to one reader may seem just right to another.

I was working with primary texts which I can't expect my readers to know well (or, in most cases, at all) so perhaps that meant I was more inclined to use longer quotations, which provide a bit more context and also give readers more of a taste of the individual authors' "voices." As far as quotations from academic secondary texts are concerned, I was hoping that the book would appeal to interested general readers as well as to romance scholars, so again perhaps that meant I included slightly longer quotes than would have been necessary if I'd only been writing for a scholarly audience. Having said all that, though, it hadn't even occurred to me that any of my quotes were too long. I think that a "reliance on long block quotes" may form part of my usual writing style. I'll bear this criticism in mind for the future but I can't promise to change; I suspect that what seems "too long" to one reader may seem just right to another.