For the latest issue of the Journal of Popular Romance Studies Stacy E. Holden's interviewed authors and editors of romance novels featuring sheikh heroes, including Lynn Raye Harris, who,

much like the ten other authors and three editors interviewed for this article—denies an explicit intent to address politics in her romance novels, but both the text of her novels and the transcripts of her interviews belie this unassuming assertion. Indeed, the author reveals a belief that her novels may well contribute to a better American understanding of the Arab world. Analyzing the sheikh, a composite Arab hero that essentializes the region’s political and cultural complexities, she notes that “I think it’s important for romance reader to think of him as a man, to know that he is sexy and desirable as a man from their own culture could be. Maybe that’s naive of me, but I choose to believe having sheikhs populate romance novels makes readers think of them as people, not terrorists or Islamic fundamentalists who hate America” (Harris, email, Follow Up, 11 February 2013).

However, it would seem that part of what these authors do in order to make "readers think of them as people, not terrorists or Islamic fundamentalists", is remove a great deal of the sheikh's non-Western culture, replacing it with "a fantasy that eschews discussion of any factual differences between the US and specific countries of the Middle East and North Africa, instead celebrating an exoticized fantasy about a glamorous Arab culture", and most of his religious beliefs:

authors express the desire to break free from the negative stereotypes of Arabs put forth in other media via the vehicle of romance, a worthy intention indeed. In order to accomplish this goal, however, authors sometimes suppress certain aspects of Arab culture and contribute inadvertently to Orientalist discourse. Islam, for example, is the principal religion of the Middle East and North Africa, and highly misunderstood by many Americans. This religion is not necessarily off limits in romance novels, though the treatment of it by authors exists on a spectrum, one that ranges from complete omission of it to oblique or (occasionally) direct interaction with it.

One of Sandra Marton's sheikhs, for instance, is

ethnically Arab, and yet he is culturally quite Western in his orientation. He is an alumnus of Yale University, and his American mother resides in California. The cover of the book deliberately eschews visual mention of Arab culture, since it features a naked man and woman in bed together. Noting that Arab clothing can be “off-putting,” Marton and her editor “had long ago agreed that my sheikh books would never feature covers in which my character was dressed in Arab garb.” Marton also insists that her stories “deliberately avoided religious discussion or religious rules.” Towards this last, her stories actually upturn the principles of the Islamic majority in the Arab world. She notes that she allows her sheikhs to drink wine, prohibited by Islam, “because I give them a backstory that involves being educated in the West” (Marton, email, sheikhs, 5 May 2-13). Her readers responded to this formula.

Holden concludes that

With its explicit images and arousing fantasies in which Arabs and Americans ultimately live together in peace, the sheikh romance novel can be read as a form of socio-political erotica. [...] Read skeptically, against the grain, these novels present a fantasy in which autocratic leaders of the Arab world—those sheikhly heroes who love American women—embrace the values of their Western fiancées and wives, reconciling their two cultures in a way that secures and privileges American interests. But read more generously, in light of their authors’ intentions, the sheikh romance novel does present a hopeful vision of the world, one which exchanges Huntington’s vision of a Clash of Civilizations for a world in which the clash between individuals from two worlds, now at odds, is ultimately an erotic clash: one which leads them to fall in love, resolve their differences, and live harmoniously together.

Megan Crane's response to Holden, also published in this issue of JPRS, is that

one could as easily substitute “Scottish highlander” or “Greek tycoon” for “sheikh” and make many of these same arguments

Up to a point, I'd agree, but I don't think it in any way undermines Holden's argument.

As someone who was born and lives in Scotland, I've found the US romance novels set in Scotland unsettling. Admittedly I haven't read many of them, but that's because the ones I did read felt as though they were set in a parallel universe. I knew I wasn't the intended reader and I wondered why this version of Scotland appealed to US readers. What is clear to me, though, is that while "Highlander" romances may resemble "sheikh" romances in some respects, I think they do some different political work in others. For example, they presumably have particular appeal to US citizens who have Scottish ancestors.

As someone who's half Spanish, romances with Spanish heroes, written by non-Spanish authors, generally also make me feel as though they're depicting a parallel version of the place inhabited by most of my family. Again, I haven't read many because I find the experience of reading them very strange. However, I've read enough to think romances with Greek, Spanish and Italian heroes play into stereotypes about "hot-blooded", macho Latin lovers. As far as I can tell, they also tend to imply that mediterranean cultures are less advanced than northern European ones in terms of their attitudes towards gender. And I notice that there aren't equal numbers of Greek, Spanish and Italian heroines, which makes this feel like these books' "implied reader" is not a Greek, Spanish or Italian woman.

Crane, however, would

argue that any fantasies in these stories have more to do with the modern woman’s belief in the power of femininity to solve problems and change lives for the better than in any kind of cultural or historical revision. For example, the popularity of this or that band of warriors (see: the alpha heroes of Nalini Singh’s Psy/Changeling series, Julie Garwood’s beloved Highlanders, Kristen Ashley’s almost-outlaw biker gang) who are forever altered once the members begin to fall in love.

I think that's part of it (although since a belief in "the power of femininity" can be deeply sexist, as in the nineteenth-century "cult of domesticity", I'm extremely wary of the idea that any particular gender identity imparts special powers). At least when this belief is played out using paranormal creatures the lines between reality and fantasy are pretty clear and if they're less so when idealised US cowboys or bikers are involved, they're probably offset by news reports etc which inform readers of the realities involved in these lifestyles. Even if they aren't, idealisation of cowboys and bikers isn't likely to cause cowboys or bikers much, if any, harm.

The situation seems to me to be significantly different when romances draw on, and thereby reinforce, racial/ethnic/cultural stereotypes which are accepted by many as being, at least partially, based in reality. Nouha al-Hegelan, for example, has stated that,

As a result of Western misinformation and lack of awareness, Arab women are unfortunately, victims of the stereotyping process. There is little understanding of either our status as women or the total context of our lives.

It is problematic when, in order to bolster "modern women's belief in the power of femininity to solve problems and change lives for the better" entire nationalities/cultures are identified as barbarian/medieval/backward so that they pose more of a challenge to, and make all the sweeter the victory of, the White Anglo woman.

------

al-Hegelan, Nouha. "Women in the Arab World." First published in Arab Perspectives 1.7 (October 1980). Republished online by Cornell University. [I quoted her in an earlier post I wrote, at Teach Me Tonight, about sheikh romances.]

Crane, Megan. "Stacy Holden's 'Love in the Desert': An Author's Response". Journal of Popular Romance Studies 5.1 (2015).

Holden, Stacy E. "Love in the Desert: Images of Arab-American Reconciliation in Contemporary Sheikh Romance Novels". Journal of Popular Romance Studies 5.1 (2015).

Simon Hardy's essay in this volume compares the "male tradition of pornographic writing" which made "use of a female narrative voice" to "erotic fiction and memoirs [...] that are genuinely written by women" in order to discover whether "female authors are producing new forms of erotica or simply assimilating patterns of erotic discourse established by the centuries-old tradition of male writers, often masquerading as female autobiographers" (25).

Simon Hardy's essay in this volume compares the "male tradition of pornographic writing" which made "use of a female narrative voice" to "erotic fiction and memoirs [...] that are genuinely written by women" in order to discover whether "female authors are producing new forms of erotica or simply assimilating patterns of erotic discourse established by the centuries-old tradition of male writers, often masquerading as female autobiographers" (25).

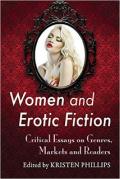

Kristen Phillips recently posted me a copy of Women and Erotic Fiction: Critical Essays on Genres, Markets and Readers, an essay collection she edited. Those essays discuss and explore a wide range of texts but it is the publication of, and responses to, Fifty Shades of Grey, which has focused attention on women's erotic fiction. Of course, as Phillips notes,

Kristen Phillips recently posted me a copy of Women and Erotic Fiction: Critical Essays on Genres, Markets and Readers, an essay collection she edited. Those essays discuss and explore a wide range of texts but it is the publication of, and responses to, Fifty Shades of Grey, which has focused attention on women's erotic fiction. Of course, as Phillips notes,