Mary observes of Tim, “It was almost as if he lived within her mind as an entity quite distinct from his real being” (73). When Danny kisses Amanda, “It was as though a missing piece of the puzzle was put back in place. He was a part of her” (71). Jesse remarks of Althea, “Truly, it was like she was inside him” (149), while Daniel lauds Jenny, “She was more than beside him: She was in him, the best part of his heart” (41). Ian Mackenzie likewise “dissolves” into Beth (217); when they kiss, his inner monologue expresses the desire “to pull her inside him, or himself inside her. If he could be part of her, everything would be all right. He would be well” (214). (133)

According to Emily M. Baldys these quotes are instances of an

oddly consistent metaphoric trope in which able-bodied characters are represented as incorporating disabled characters, literally and metaphorically taking disabled characters inside themselves. I contend that the trope of romantic incorporation is motivated by the threatening potential of disabled sexuality and used [...] to enact the bodily containment of threat. (133)

I'm not so sure. As Baldys admits, in the third example "Morsi’s phrasing places the able-bodied character inside the disabled character instead of the other way around" (133). More significantly, the "trope of romantic incorporation" is one I've seen frequently in novels in which both characters are able-bodied. Here's an example from Carol Arens' Renegade Most Wanted (2012):

If it had been possible for a woman's soul to flow out of her body and into a man, that's the way it would happen. If not for the constraints of the flesh, she would be right there, inside Matt's heart. (317)

A very short while later the "romantic incorporation" is reversed and made literal as "He slipped inside her" (318) and

he rocked against her womb. A wave crashed inside her. It washed pleasure from the point of their joining to her clenching fingers, then tumbled to the tips of her toes.

Maybe flesh was no barrier to souls after all.

Hadn't her wedding vows declared that the two shall become one flesh? (318-19)

I think passages describing "romantic incorporation" can perhaps be explained by extrapolating a little from some of the ideas Baldys outlined earlier in her essay.

Compulsory heterosexuality—the ideology that positions heterosexuality as a default, biologically derived identity and enforces its normalcy through pervasive cultural mechanisms—has been a common idiom in queer and feminist studies since 1980, when Adrienne Rich published her influential essay coining the term. More recently, scholars writing within disability studies have proposed an analogous conception to Rich’s formative idea. “Compulsory able-bodiedness” is an ideology that positions able-bodiedness as the default position and bolsters itself through cultural forms that represent ability as original, authentic, and normal. This concept, as theorized by Alison Kafer and Robert McRuer, posits a complex interrelationship between heterosexuality and able-bodiedness. Kafer explains that heterosexuality is threatened by disability’s associations with deviance, while able-bodiedness is threatened by the relationship of queerness to illness and medicalization (81–82). Thus, the two ideologies are “entwined” (in McRuer’s terminology) and “imbricated” (in Kafer’s) such that each is contingent on the other: the default heterosexual subject is necessarily able-bodied, and the default able-bodied subject is necessarily heterosexual. (127)

The "trope of romantic incorporation" seems to suggest that there is a third ideology entwined with the other two. Catherine Roach has observed that

To the ancient and perennial question of how to define and live the good life, how to achieve happiness and fulfillment, American pop culture’s resounding answer is through the narrative of romance, sex, and love. The happily-in-love, pair-bonded (generally, although increasingly not exclusively, heterosexual) couple is made into a near-mandatory norm by the media and popular culture, as this romance story is endlessly taught and replayed in a multiplicity of cultural sites.

Given that these narratives are "increasingly not exclusively [...] heterosexual," I think they cannot simply be described as a part of "compulsory heterosexuality." Rather, they perhaps indicate the existence of what one might term "compulsory coupledom" which often, but not always, complements "compulsory heterosexuality" and "compulsory able-bodiedness" and which should at times be analysed separately from them.

According to Bella M. DePaulo and Wendy L. Morris

A widespread form of bias has slipped under our cultural and academic radar. People who are single are targets of singlism: negative stereotypes and discrimination. Compared to married or coupled people, who are often described in very positive terms, singles are assumed to be immature, maladjusted, and self-centered. (251)

Given that romances always feature "individuals falling in love and struggling to make the relationship work" who "are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love" (RWA), it would seem likely that romances could be seen as a "cultural mechanism" which helps to enforce "compulsory coupledom." Certainly Kyra Kramer and I observed a pattern in many romances in which becoming part of a couple completes/perfects the "Phallus" of the romance hero:

Given that romances always feature "individuals falling in love and struggling to make the relationship work" who "are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love" (RWA), it would seem likely that romances could be seen as a "cultural mechanism" which helps to enforce "compulsory coupledom." Certainly Kyra Kramer and I observed a pattern in many romances in which becoming part of a couple completes/perfects the "Phallus" of the romance hero:

“Phallus” refers to the socio-political body which expresses aspects of masculinity associated with the Father, such as authority, the capacity to administer punishment, and the ability to love and care for those under his protection. If a full range of Phallic traits is evinced by a hero then his socio-political body is a Completed Phallus.

At the beginning of a romance novel, however, most heroes have Incomplete Phalluses. Such heroes tend to demonstrate authoritarian or aggressive aspects of Phallic masculinity, including “the threat of violence, the law-giving nature, the ownership of the world, a power vested in physical presence” (Cook 154), and few of the softer qualities, such as care-giving. In a romance in which the Incomplete Phallus displays many of the negative characteristics of men in patriarchal culture, the hero of the romance can also be “its villain, a potent symbol of all the obstacles life presents to women” (Phillips 57). [...]

The feminine equivalent of the Phallus is the socio-political body we shall term the Prism [...]. Even though a romance heroine’s Prism is initially incomplete, it nonetheless focuses her hero’s powers, enabling his Incomplete Phallus to fulfil its potential in a socially acceptable manner and become a Completed Phallus.

Becoming part of a couple also completes/perfects the heroine's Prism.

There are, of course, romances which do not follow this pattern and in any case I would not wish to suggest that all romances imply that the unpartnered are incomplete: the protagonists of romance are sometimes depicted in contexts which include happily-single secondary characters. Nonetheless, the extent to which such contexts can mitigate the focus on the achievement of a romantic relationship is limited because, by definition, a romance has to prioritise the depiction of the central couple (or occasionally threesome or more).

Baldys states that the "demands of compulsory heterosexuality and compulsory able-bodiedness" are "intertwined" (127); it appears they may also be intertwined with compulsory coupledom:

never-married men do run the risk of being labelled 'queers', 'fairies' or 'queens'.

In an analysis of Australian attitudes, Penman and Stolk (1983) found that single women were described as unfulfilled, incomplete, unattractive, and less happy than married women" (Callan and Noller 97, emphasis added)

The idea that single people are "incomplete" evidently has a long history, for Plato's Symposium contains a tale in which it is explained that "the desire and pursuit of the whole is called love" and that it came about because

the primeval man was round, his back and sides forming a circle; and he had four hands and four feet, one head with two faces, looking opposite ways, set on a round neck and precisely alike; also four ears, two privy members, and the remainder to correspond. He could walk upright as men now do, backwards or forwards as he pleased, and he could also roll over and over at a great pace, turning on his four hands and four feet, eight in all, like tumblers going over and over with their legs in the air; this was when he wanted to run fast.

These early humans attacked the gods and as a punishment Zeus declared that he would "cut them in two and then they will be diminished in strength and increased in numbers." According to this myth, all humans are incomplete, and when we fall in love it is because we seek to become whole once more. Obviously the story is not one which can be taken at all seriously but there is nonetheless a

tendency to refer to marriage as a union of two persons into oneness [which] often prompts married people to refer to their spouse as their "other half" or "better half". Unfortunately, it gives rise to the idea that an unmarried person must be fractured, being only half of a whole.

Therefore, the implication is that we must go about looking for another person to provide completion to our being. In other words, a person who is unmarried is incomplete as a person and has less than a full existence than a married person has. (Yeo 11-12)

In romance novels, the formation of a couple sometimes accompanies the curing of disabilities. Baldys notes that

One strain of ableist fantasy suggests that cognitive disability can be “overcome” in one way or another through the extraordinary power of heterosexual relationships. Simi Linton identifies such an “overcoming rhetoric” as one of the clichés that structure dominant meanings and response patterns assigned to disability. “The idea that someone can overcome a disability,” she writes, implies “personal triumph over a personal condition.” Linton argues that this idea is not a concept native to the disability community, but rather “a wish fulfillment generated from the outside” (165). This wish-fulfilling fantasy, in romance novels, finds expression in a process of narrative rehabilitation through which the effects of disability are represented as mitigated or overcome by the characters’ blossoming love. (Baldys 134)

Although I've not read the novel Baldys gives as an example of "the most extreme (and credulity-straining) measures to rehabilitate disability" (134), I've come across a number of romances in which blind protagonists regain their sight as well as novels in which previously infertile protagonists become pregnant or father children. Deborah Chappel has observed the transformations which occur in LaVyrle Spencer's novels and argues that

the changes in Spencer's protagonists (regularization of speech, dimming of freckles, development of healthy-looking bodies) are sometimes so pronounced that it seems inner, emotional reality has the power to improve the material world. Love, and the hope love engenders, operate as forces in the world. [...] Thus, in The Gamble Agatha's limp becomes less and less pronounced and she is able to achieve the three seemingly impossible wishes she expressed in the opening chapters: she can dance, swim, and ride a horse. (110)

Baldys believes that the depictions of disability in romances differ "from depictions in canonical literature, where disability has traditionally functioned as a 'cipher of metaphysical or divine significance' (Quayson 17)" (138) but I'm not so sure that this is the case. As Catherine Roach has observed, "The story of romance is the most powerful narrative in Western art and culture, sharing roots with Christianity and functioning as a mythic story about the meaning and purpose of life, particularly in regards to the HEA ending of redemption and wholeness."

Perhaps in romances the curing of protagonists' disabilities, which takes to a new and literal level the metaphorical use of words suggesting that love makes a person whole/completes them, serves as a kind of secular miracle bearing witness to the power of love (and compulsory coupledom, compulsory heterosexuality and compusory able-bodiedness) by implying that when a man is united to his wife, not only are they "no more twain, but one flesh" (Matthew 19; 6) but that sometimes, in addition, "The blind receive their sight, and the lame walk" (Matthew 11:5).

----

Arens, Carol. Renegade Most Wanted. Richmond, Surrey: Mills & Boon, 2012.

Baldys, Emily M. "Disabled Sexuality, Incorporated: The Compulsions of Popular Romance." Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 6.2 (2012), 125–141.

Callan, Victor J. and Patricia Noller. Marriage and the Family. North Ryde, NSW: Methuen, 1987.

Chappel, Deborah K. "LaVyrle Spencer and the Anti-Essentialist Argument." Paradoxa 3.1-2 (1997), 107-120.

DePaulo, Bella M. and Wendy L. Morris. "The Unrecognized Stereotyping and Discrimination against Singles." Current Directions in Psychological Science 15.5 (2006), 251-254.

Plato. Symposium. Trans. Benjamin Jowett. The Internet Classics Archive.

Roach, Catherine. "Getting a Good Man to Love: Popular Romance Fiction and the Problem of Patriarchy." Journal of Popular Romance Studies 1.1 (2010).

RWA. "About the Romance Genre."

Vivanco, Laura, and Kyra Kramer. “There Are Six Bodies in This Relationship: An Anthropological Approach to the Romance Genre”, Journal of Popular Romance Studies 1.1 (2010).

Yeo, Anthony. Partners in Life: Your Guide to Lasting Marriage. Singapore: Armour, 1999.

----

The image of a dovetail joint comes via Flickr where it was made available under a Creative Commons licence by Jordanhill School D&T Dept.

When the Romantic Novelists' Association was inaugurated in January 1960, Barbara Cartland was one of two Vice Presidents and she

When the Romantic Novelists' Association was inaugurated in January 1960, Barbara Cartland was one of two Vice Presidents and she In “What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?”: Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel," Marlon B. Ross states that

In “What’s Love But a Second Hand Emotion?”: Man-on-Man Passion in the Contemporary Black Gay Romance Novel," Marlon B. Ross states that

To desire is necessarily to exist in a state of fantasy: it is to entertain the possibility of obtaining something one does not have - power, love, adventure. Given that all desire is fantastical by its very nature, it might seem odd that some projections of desire are criticized because they seem inauthentic. Popular romance fiction, for instance, has long been derided as the worst kind of fantasy. There is the sense that publishers such as Silhouette, Harlequin and Mills & Boon provide emotional and erotic titillation for women who are too weak to achieve fulfilment in 'real life'. Only such fools, with no genuine hold on reality, could lend credence to the impossibly beautiful, monolithic, creatures to be found in these novels. There is the suggestion that these works are not so much fantasy as false consciousness. The passion is at once euphemized and overstated; this is pornography for those who cannot bear to own up to sexual appetite. Alternatively, such caricatures of desire may provide an excessive compensation in the sphere of the erotic for a variety of other wants: the imaginary lover can requite not merely sexual loneliness, but also a poorly paid job, or a general feeling of insignificance.

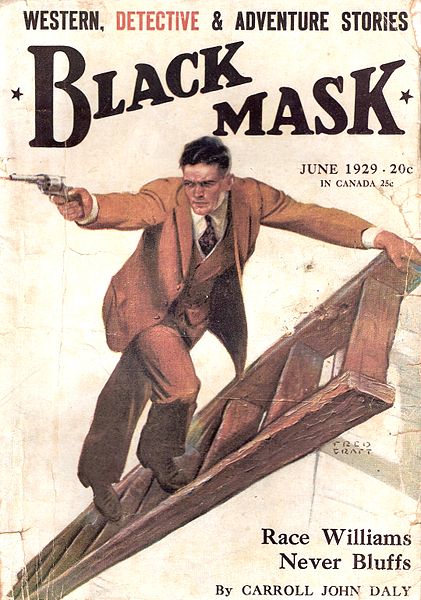

To desire is necessarily to exist in a state of fantasy: it is to entertain the possibility of obtaining something one does not have - power, love, adventure. Given that all desire is fantastical by its very nature, it might seem odd that some projections of desire are criticized because they seem inauthentic. Popular romance fiction, for instance, has long been derided as the worst kind of fantasy. There is the sense that publishers such as Silhouette, Harlequin and Mills & Boon provide emotional and erotic titillation for women who are too weak to achieve fulfilment in 'real life'. Only such fools, with no genuine hold on reality, could lend credence to the impossibly beautiful, monolithic, creatures to be found in these novels. There is the suggestion that these works are not so much fantasy as false consciousness. The passion is at once euphemized and overstated; this is pornography for those who cannot bear to own up to sexual appetite. Alternatively, such caricatures of desire may provide an excessive compensation in the sphere of the erotic for a variety of other wants: the imaginary lover can requite not merely sexual loneliness, but also a poorly paid job, or a general feeling of insignificance.  Of course such criticism could also be offered of the characters and scenarios of male-oriented popular fiction, who are usually every bit as predictable and fantastic: the spy who is equally adept at unlocking women's desires and unravelling the plans of evil empires; the silent, unbreakable Western hero; the detective who outwits and outpunches low-life villains. The hard-boiled quality of masculine fictions suggests a claiming of the real, even though we as real readers in the real world may detect the wishfulness of it all. (Stoneley 223)

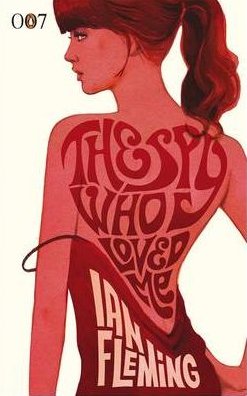

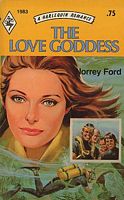

Of course such criticism could also be offered of the characters and scenarios of male-oriented popular fiction, who are usually every bit as predictable and fantastic: the spy who is equally adept at unlocking women's desires and unravelling the plans of evil empires; the silent, unbreakable Western hero; the detective who outwits and outpunches low-life villains. The hard-boiled quality of masculine fictions suggests a claiming of the real, even though we as real readers in the real world may detect the wishfulness of it all. (Stoneley 223) Norrey Ford's The Love Goddess (1976) is a novel about an academic. Admittedly, Professor Bart Ransom's research is rather more exciting than mine: he's working on an underwater archaeology site in the Aegean and requires absolute secrecy from his collaborators because the wreck promises to be so important it would attract the attention of "Pirates, hijackers! The word gold could bring them running from all quarters of the earth" (42). My research won't produce any gold or priceless ancient artefacts but there's something about Bart's explanation of how he feels about his work that did strike a chord with me:

Norrey Ford's The Love Goddess (1976) is a novel about an academic. Admittedly, Professor Bart Ransom's research is rather more exciting than mine: he's working on an underwater archaeology site in the Aegean and requires absolute secrecy from his collaborators because the wreck promises to be so important it would attract the attention of "Pirates, hijackers! The word gold could bring them running from all quarters of the earth" (42). My research won't produce any gold or priceless ancient artefacts but there's something about Bart's explanation of how he feels about his work that did strike a chord with me: Writing about "chick flicks," Imelda Whelehan has commented that their

Writing about "chick flicks," Imelda Whelehan has commented that their Given that romances always feature "individuals falling in love and struggling to make the relationship work" who "are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love" (

Given that romances always feature "individuals falling in love and struggling to make the relationship work" who "are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love" (