Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns -- the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones. (Secretary Rumsfeld, DoD News Briefing, 12 Feb. 12 2002)

In the context of the study of popular culture, "reports that say something hasn't happened [before] are always interesting to me." One relatively recent example, examined by Pam Rosenthal, is

In the context of the study of popular culture, "reports that say something hasn't happened [before] are always interesting to me." One relatively recent example, examined by Pam Rosenthal, is

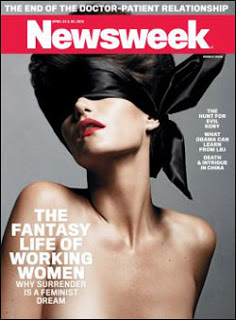

Katie Roiphe’s Newsweek cover story a few weeks ago, which purported to let us in on a couple of big brave surprising secrets.

- That young successful working women might have erotic fantasy needs social equality can’t satisfy.

- That feminists are “perplexed,” and “outraged” by this situation.

- And that therefore feminism is some clueless, useless, irrelevant call back to some mythical “barricades.”

Pretty standard Roiphe, I discovered [...]: like a girl Columbus, her thing evidently is to “discover” something that’s been there all along, and then to congratulate herself for her boldness while conveniently forgetting that anybody – least of all any of those irrelevant feminists – had ever had similar (if not braver, more honest, challenging, nuanced, and radical) thoughts on the subject.

Pam was, obviously, unimpressed by Roiphe's report because what are apparently "unknown unknowns" for Roiphe are "known knowns" for Pam:

The story of how women got our own erotic reading still has yet to be told in its entirety. But if I were to try I’d begin by positing two distinct yet subtly related sources, both pretty contemporaneous. The advent of the bodice-rippers and of the sex-positive feminist discussion I cut my writing teeth on.

It was at this point that I questioned Pam's starting point. Why, I asked, not start further back still with, for example,

E. M. Hull’s The Sheik (1919) which, according to Q D Leavis, was “to be seen in the hands of every typist”? Or Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks (1907)? I haven’t actually read it, because it’s more romantic/erotic fiction rather than romance, but

With hindsight it can be argued that Three Weeks broke down a great deal of Edwardian sexual prejudice and hypocrisy: it can, however, also be seen as a wildly titillating fantasy and a foray into voyeurism. (Mary Cadogan, And Then Their Hearts Stood Still, page 75)

And then, having hastily done a little bit more research, I added:

Sarah Wintle’s article on The Sheik, [...] puts it, as you say, “in the context of a period of sexual reform”:

To flaunt this book in the early 1920s, Alexander Walker suggests in his biography of Valentino, was to flaunt your emancipation and daring; to enjoy openly its primitive sexual fantasies was to show a truly modern insouciance in the face of the fashionably shocking vagaries and transgressive energies of human feeling celebrated in modernist and jazz-age primitivism. Such energies and drives had recently been highlighted by Freudian psychoanalysis and by the popularizing of the new science of sexology which had led to the publication, in the same year as The Sheik, of Marie Stopes’s manual, Married Love. In one way at least the book’s open treatment of female sexuality contributed to its popular version of modernity. (Wintle 294-95)

Could we go back further still? Jodi McAlister has recently drawn parallels between modern popular romance novels and the works of Delarivier Manley, Eliza Haywood and Aphra Behn, which

got thrown in the immoral rather than the immortal basket [...] not because of some arbitrary distinction between the romance and the novel but because they were dangerous. Their literary form is the form Richardson was trying to remake in a moral form when he wrote Pamela. Social anxieties about what women read and what they took from it were rife [...]. Female fantasy, whether or sex or violence or revenge or passion, taking place as it did outside the controlled bounds of patriarchal society, was considered frightening and perilous.

To me the history of erotic fiction is still pretty much a "known unknown" or even an "unknown unknown" and, as a medievalist, it seems to me as though I've leaped from a period in which, "Contrary to the modern stereotype that views males as more susceptible to sexual desire than females, [...] women were often seen as much more lustful than men" (Decameron Web), to a period in which it's necessary to argue that women are at least as interested in sex as men are. Quite how that cultural shift took place is another "known unknown" to me because I haven't done much background reading on the history of sex and sexualities.

I can only conclude that any scholar of popular culture has to tread extremely carefully. We may have detailed maps of the "known knowns," but beyond them lie the "known unknowns," those areas of popular culture about which we know we know little. And then, beyond them, are the "unknown unknowns." Before we accept reports that "something hasn't happened" before, we might want to try to do more research, to verify whether one of those "unknown unknowns" is the knowledge that it has, in fact, happened before.

I'm well aware that, however much I study popular romance, there will always be vast areas that remain "known unknowns" to me. I hope, therefore, that my next post, which looks at an article by Erin S. Young, will be taken not as the gloating of a smugly self-satisfied know-it-all, but as the conclusions of a romance scholar who is constantly being humbled by finding out just how much she still has to learn about popular culture.

-----

- Cadogan, Mary. And Then Their Hearts Stood Still: An Exuberant Look at Romantic Fiction Past and Present. London: Macmillan, 1994.

- Wintle, Sarah. ‘The Sheik: What Can be Made of a Daydream’, Women: A Cultural Review 7.3 (1996): 291-302.