The RWA revises its definition of the romance novel from time to time, but it used to state, among other things, that

Romance novels end in a way that makes the reader feel good. Romance novels are based on the idea of an innate emotional justice -- the notion that good people in the world are rewarded and evil people are punished. In a romance, the lovers who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love.

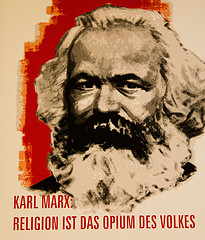

This isn't quite a promise of eternal life with a God who is love but there is, as Bridget Fowler has observed, “a parallel with religion, to which the romance bears strong resemblance [...] religion is [...] the plane on which the masses express their true material and social needs [...] the romance is also the ‘heart of a heartless world’” (174-75). Fowler is quoting here from Karl Marx, who stated that “The wretchedness of religion is at once an expression of and a protest against real wretchedness. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people” (131). David Margolies, too, uses parts of this quotation from Marx in order to describe romances: “As in Marx’s description of religion as an opiate and the heart of a heartless world, the romance offers escape from an oppressive reality, or justifies it as a vale of tears that women pass through to salvation” (12).

This isn't quite a promise of eternal life with a God who is love but there is, as Bridget Fowler has observed, “a parallel with religion, to which the romance bears strong resemblance [...] religion is [...] the plane on which the masses express their true material and social needs [...] the romance is also the ‘heart of a heartless world’” (174-75). Fowler is quoting here from Karl Marx, who stated that “The wretchedness of religion is at once an expression of and a protest against real wretchedness. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people” (131). David Margolies, too, uses parts of this quotation from Marx in order to describe romances: “As in Marx’s description of religion as an opiate and the heart of a heartless world, the romance offers escape from an oppressive reality, or justifies it as a vale of tears that women pass through to salvation” (12).

Fowler notes that “Gramsci was [...] the first to extend to mass culture the Marxist analysis of religion as an opiate, later to be followed by Brecht, who referred cynically to the culture industry as ‘a branch of the capitalist narcotics industry’” (31). With specific reference to Mills & Boon romances, Alan Boon once acknowledged that “It has been said that our books could take the place of valium, so that women who take these drugs would get an equal effect from reading our novels” (McAleer 2) and “the assumption that Harlequins are ‘addictive’ [...] has been frequently stated by representatives of the company” (Jensen 41). Tania Modleski analysed the supposed effects of consuming this addictive product:

Harlequins, in presenting a heroine who has escaped psychic conflicts, inevitably increase the reader’s own psychic conflicts, thus creating an even greater dependency on the literature. This lends credence to the [...] commonly accepted theory of popular art as narcotic. As medical researchers are now discovering, certain tranquilizers taken to relieve anxiety are, though temporarily helpful, ultimately anxiety-producing. The user must constantly increase the dosage of the drug in order to alleviate problems aggravated by the drug itself. (57)

Theresa L. Ebert also draws parallels between religion and romance novels, but rather than drawing on Marx's metaphor of opium addiction, she turns to Hegel:

Religion as a mode of thinking, what Hegel calls ‘picture-thinking’ (Vorstellung), is the global logic of the popular. Both religion and the popular render the unseen, the immaterial, the abstract as sensuous, material, and individual – the ‘Word made flesh’ – through ‘picture-thinking’. According to Hegel, ‘the reality enclosed within religion’ and, I would argue, within the popular, ‘is the shape and the guise of its picture-thinking’. The ‘guise’ of reality in ‘picture-thinking’, whether religious or popular, is an inverted reality and through its sensuous, particular, imagining, produces an inverted consciousness.

She adds that

Like religion, popular texts explain the material by the immaterial and substitute a change of heart in the subject for the material transformation of objective conditions. Popular texts such as women’s romances and chick lit, in other words, re-orient the subject but leave intact the objective social conditions in which she lives. They do this by supplanting social justice and economic equality with love, intimacy, and caring. The affective is inverted into the material and the material into the affective.

The importance the RWA's definition gives to "emotional justice," would seem to provide support for this view of popular romances. However, the very parallel drawn by Ebert and others between religion and romance novels suggests that that it is not inevitable that romances should ignore the "material transformation of objective conditions." For instance,

Liberation theology emerged as part of a broad effort to rethink the meaning of religious experience and the role the Catholic church ought to play in society and politics. The poor are central to these efforts, but not in the traditional sense of objects of charity or of hope for a better life after death. The idea that the poor shall inherit the earth takes on more immediate and activist tones, with concrete efforts to enhance the role of poor people as legitimate participants in religion, society and politics. Institutions, the Church included, were urged not only to help, speak for, and defend poor people, but also to trust and empower them, providing tools of organization and a moral vocabulary that made activism and equality both legitimate and possible. (Levine)

and

The central importance to Friends [Quakers] of the Testimony of Equality is exemplified by their corollary theological belief in "that of God in everyone." The idea that everyone has at least potential access to God’s leadings was a radical declaration of theological equality when first formulated by [George] Fox. It has since gone on to play a defining role in the history of Quakerism. The principle of equality is manifested, for instance, in the recognition and status accorded to the rights and gifts of women from the very earliest incarnations of the Quaker movement. To a group of people who held that women no more have souls than does a goose, Fox countered with the words of Mary, who said that: “My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour" (Fox, The Journal, 1646-7, pg. 11). In the following century, the Testimony of Equality led Friends to free their slaves and assume leading roles in calling for the abolition of slavery. By the time of the American Revolution, it had become plausible to declare the fundamental equality of all human beings to be a self-evident truth; though it would still take centuries for this truth to be fully enacted in the laws of the land. (Earlham School of Religion)

African-American romance author Beverly Jenkins sees her work as having both a political and a religious dimension:

it seems like that it’s been my ministry—tap, tap, tap on the shoulder—to do that, to bring that 19th century to life in a way that people can access it, people can be proud of who they were, and still see the struggle in a real light—you know, a real light, so that it’s not glossed over.

As Rita B. Dandridge has written, "Black women's historical romances document race as a social and political construct that is anchored to a systemic body of laws based on color difference, privileging whites over blacks" (5-6).

In For Love and Money I was very focused on reading romances as literature (as opposed to "trash") and therefore didn't have spend much time examining their implicit (and occasionally explicit) politics. It's something I'd like to look at more closely in future.

---------

Dandridge, Rita B. Black Women's Activism: Reading African American Women's Historical Romances. New York: Peter Lang, 2004.

Earlham School of Religion. "The Quaker Testimonies."

Ebert,Teresa L. "Hegel's “picture-thinking” as the Interpretive Logic of the Popular." Textual Practice. iFirst Article (2012). [Abstract]

Fowler, Bridget. The Alienated Reader: Women and Popular Romantic Literature in the Twentieth Century. Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1991.

Jenkins, Beverly. "Jenkins on History." Transcript downloaded from The Popular Romance Project.

Jensen, Margaret Ann. Love’s $weet Return: The Harlequin Story. Toronto: Women’s Educational P., 1984.

Levine, Daniel H. "The Future of Liberation Theology." The Journal of the International Institute 2.2 (1995).

Margolies, David. “Mills & Boon: Guilt Without Sex.” Red Letters 14 (1982-83): 5-13.

Marx, Karl. “A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction.” Trans. Annette Jolin and Joseph O’Malley. Critique of Hegel’s “Philosphy of Right.” Ed. Joseph O’Malley. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1970. 129-142.

McAleer, Joseph. Passion’s Fortune: The Story of Mills & Boon. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

Modleski, Tania. Loving with a Vengeance: Mass-produced Fantasies for Women. 1982. New York: Routledge, 1990.

RWA, "Romance Novels - What Are They?" 8 July 2007. Preserved by the Internet Archive.

The image was created on the 23 February 2012 at the Städtmuseum in Trier by Antonio Ponte (saigneurdeguerre) and made available under a Creative Commons licence at Flickr.