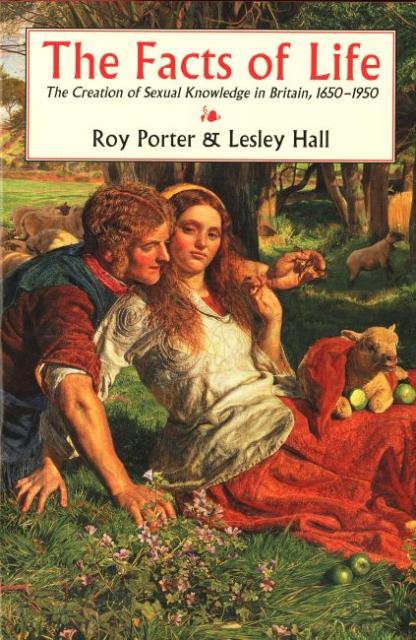

Roy Porter and Lesley Hall's The Facts of Life: The Creation of Sexual Knowledge in Britain, 1650-1950, published in 1995, was apparently "the first scholarly survey of the rise of English-language treatises of sexual knowledge and guidance, and it closely scrutinizes teachings about sexual functions and disorders, physical and moral tenets about sexual activity, prescribed and proscribed coital positions, and views about sexual pleasures and proprieties" (3). As they point out, however,

Roy Porter and Lesley Hall's The Facts of Life: The Creation of Sexual Knowledge in Britain, 1650-1950, published in 1995, was apparently "the first scholarly survey of the rise of English-language treatises of sexual knowledge and guidance, and it closely scrutinizes teachings about sexual functions and disorders, physical and moral tenets about sexual activity, prescribed and proscribed coital positions, and views about sexual pleasures and proprieties" (3). As they point out, however,

We cannot blithely assume that readers took the advice the manuals gave [...]. Reading is not passive; people read actively and selectively, rejecting unwelcome advice and absorbing mainly what they believe already. Reading may confirm habits rather than change them. In any case, people do not always read the books they buy or are given. (6)

Nonetheless, the words used in the manuals are important because

sexuality could not exist in the culture without words, images, metaphors and symbols to represent it. Put more strongly, the sexual is such a complex and contested domain, mightily charged with associations and emotions, norms and values, that the terms in which it is posited determine the entity itself.

This further raises questions of knowledge and power: who commands the idiom through which the sexual is defined and prescribed? Is the language of sex the idiom of common speech, the jargon of medicine or of moral philosophy, the prerogative of experts? Is talking sex expressing oneself, regulating others or engaging in shared exchanges? Not least [...] the discourse of sex conveys erotic pleasures that may be independent of the pleasures of coitus itself. (8)

I think these are questions which are of great relevance to popular romance, which uses words and metaphors to represent sex. Porter and Hall themselves mention that

Work is beginning to appear on the fiction in women's magazines and the sexual messages it conveyed. Billie Melman has investigated certain genres of the 1920s, and Joseph McAleer has analysed the 'story' magazines as well as popular romance literature. Little work has been done generally on changing messages about sexuality in fiction. The scientist Julian Huxley remarked in his unused deposition in defence of The Well of Loneliness: 'novels are the chief method for the average man and woman to get knowledge of life'. (267)

Do romance authors constitute themselves as "experts" in the realm of sexuality by virtue of writing about it? The fact that "the discourse of sex conveys erotic pleasures" has led some to denigrate romance as "pornography"; others, however, might argue that its fascination with female virgins and heterosexual penetrative sex has reinforced very conservative notions of "sex". Are romance authors expressing themselves, regulating others and/or engaging in shared exchanges?

--------

Porter, Roy & Lesley Hall. The Facts of Life: The Creation of Sexual Knowledge in Britain, 1650-1950. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995.