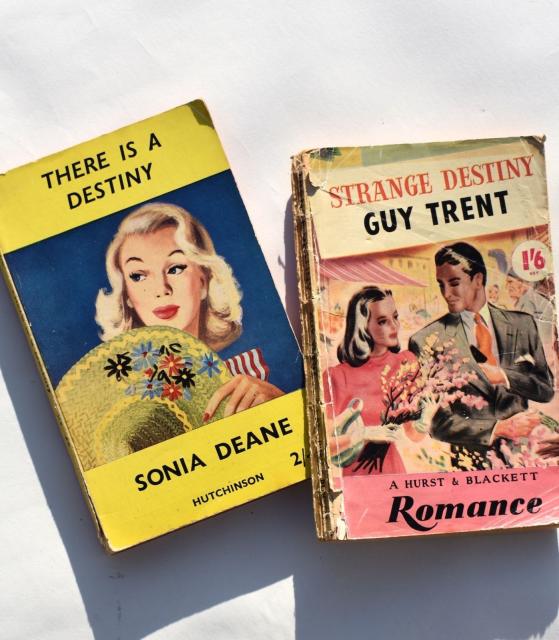

Hutchison and Hurst & Blackett Paperback Romances

Hutchison and Hurst & Blackett Paperback Romances

Although Harlequin and Mills & Boon tend to be the names we think of in relation to short paperback romances, for a long time Mills & Boon specialised in hardbacks, for the library market. Competing with them, in the paperback format, were romances by other publishers:

a number of British firms were following the trail blazed by Allen Lane and Penguin Books in 1935. Pan, Corgi, Panther, Sphere, Cherry Tree, and Fontana paperback imprints, featuring romance, crime, and war stories, appeared after the war. [...] Mills & Boon did negotiate paperback editions of some novels before Harlequin's offer in 1957, but these were limited and infrequent. [...] Corgi Books picked up Mills & Boon's Doctor-Nurse titles for its 2s. 'Corgi Romance' series [...]. (McAleer 116)

It wasn't until 1964 that "Mills & Boon started printing paperback novels in Britain (as opposed to importing a limited number of novels printed in Canada)" (114).

Not mentioned by McAleer in the quotes above are Hurst & Blackett and Hutchison, but they too clearly had an interest in this market and, as is evident from the photo above, Hurst & Blackett were clearly labelling their category-length romances as "Romance". I recently bought the paperback romances in that photo from Ebay; they caught my attention because they were paperbacks published in the late 1940s or early 1950s. No publication dates are given in the copies I have, which are not first editions, but according to one library catalogue Sonia Deane's There is a Destiny dates from 1948 and Guy Trent's Strange Destiny from 1949.

I haven't seen much written about early romance paperbacks like these, which reminds me that although we do have some broad histories of popular romances, such as Rachel Anderson's The Purple Heart Throbs (1974) and more specialised histories such as those of Harlequin (e.g. Paul Grescoe's The Merchants of Venus (1996)), there are still a lot of gaps to be filled and, even today, some aspects of the history of the romance-reading community remain ephemeral (such as the digital discussion groups documented in this 2009 post by Jane of Dear Author).

In "Postbellum, Pre-Harlequin: American Romance Publishing in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century" Bill Gleason fills in some of the gaps in our knowledge of much earlier romance publishing and his findings challenge a number of preconceptions which exist about the history of romance fiction. These preconceptions exist, largely, because the history of this type of fiction is so incomplete and works which were hugely popular in the past have fallen into obscurity. Gleason

suggest[s] that many of the elements of American romance publishing we currently take for granted as late-twentieth century innovations, including multiple points of view, proliferating subgenres, and diverse publishing venues, were already distinctive features of the buzzing, blooming, romance market [of the late 19th century]. (57)

According to Gleason, by the 1880s and 1890s there were increasing numbers of "dime novel libraries that catered predominantly, and often specifically, to romance readers" (64) and

"From around the mid-1880s the dime novel libraries became not only more numerous but also more specialized, separating works out not only broadly by genre ... but also narrowly by sub-genre," notes media historian Graham Law. "'Clover', 'Heart', 'Primrose', 'Sweetheart', and 'Violet', were among the epithets used to denote romance libraries aimed at female readers." [...] The writer in whose work the specialized romance series [...] invested most heavily was [...] Charlotte M. Brame [...]. Like other English authors before the passage of the International Copyright Act of 1891, Brame, who wrote "somewhere in the region of 130 novels during her lifetime," had her work routinely pirated in the United States. (65)

Those sound rather like the titles of modern category romance "lines."

A short biography of Brame, along with a bibliography of her works, by Graham Law, Gregory Drozdz and Debby McNally can be found online. Gleason focuses on Wedded and Parted, which

tells the story of 18-year-old Lady Ianthe Carr, whose father, an English Earl, has gambled away their fortune speculating on a mine. To save the family from ruin, Ianthe's father implores her to marry the young man whose father now owns the title to their family estate. Although the young man, Herman Culross, is honest, hard-working and handsome [...] Ianthe treats Herman with contempt. [...] Only when he is gone does Ianthe recognise his true nobility. (66)

If you want to find out what happens next, the whole novel can be found online here. I haven't read it all, but it's category-length and ends with a grovel and an HEA.

----

Gleason, William A. 'Postbellum, "Pre-Harlequin: American Romance Publishing in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century," Romance Fiction and American Culture: Love as the Practice of Freedom?'' Ed. William A. Gleason and Eric Murphy Selinger (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2016), pp. 57-70.

McAleer, Joseph. Passion's Fortune: The Story of Mills & Boon. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

----

Edited to add:

Over on Twitter, Elizabeth Lane's shared some covers of more early paperback romances. I wasn't able to find any mention of their authors in Twentieth Century Romance and Gothic Writers (which doesn't have Guy Trent or Sonia Deane either).

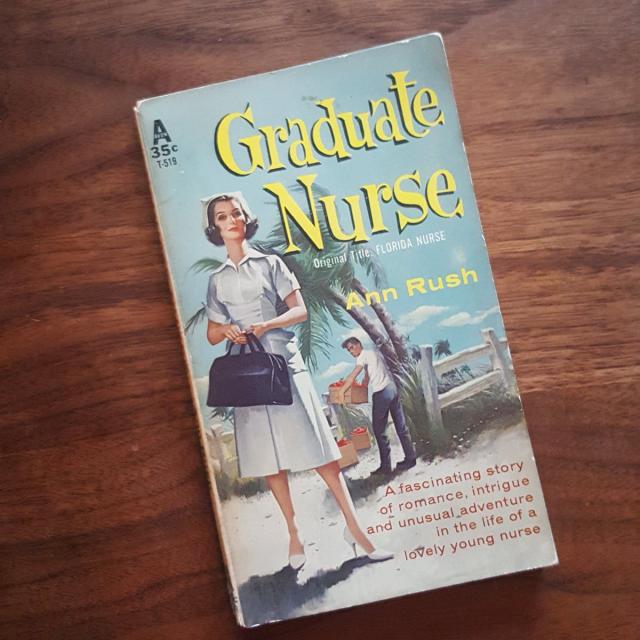

Graduate Nurse by Ann Rush

Graduate Nurse by Ann Rush

Elizabeth notes that this edition was published in 1956 by Avon but there must have been an earlier edition as the cover mentions that it was originally titled Florida Nurse.

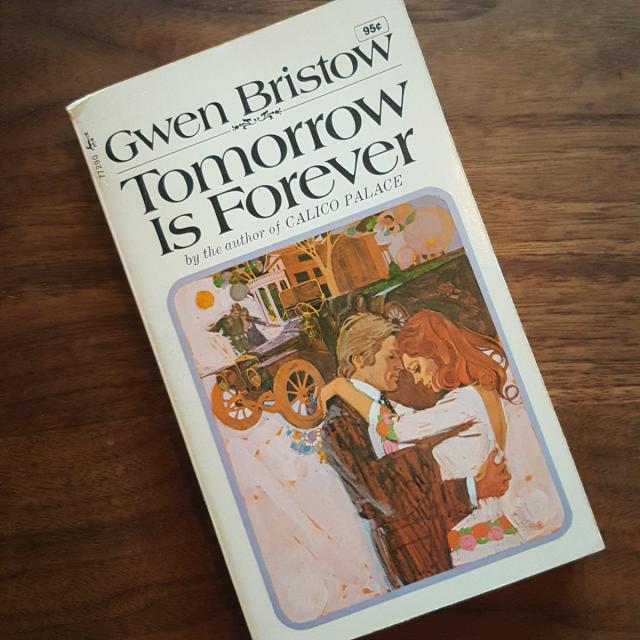

Tomorrow is Forever by Gwen Bristow

Tomorrow is Forever by Gwen Bristow

Elizabeth says 'this one is Pocket from 1971, but it says "Thomas Y. Crowell edition published 1943".'